Moving to the cloud unlocks incredible speed and scale, but it also introduces complex security challenges that can't be solved with a generic, high-level approach. A misconfigured IAM role, an overly permissive network rule, or an unpatched container can expose critical data and infrastructure, turning a minor oversight into a significant breach. Traditional on-premise security models often fail in dynamic cloud environments, leaving DevOps and engineering teams navigating a minefield of potential vulnerabilities without a clear, actionable plan.

This article provides a deeply technical and actionable cloud security checklist designed specifically for engineers, engineering leaders, and DevOps teams. We will move beyond the obvious advice and dive straight into the specific controls, configurations, and automation strategies you need to implement across ten critical domains. This guide covers everything from identity and access management and network segmentation to data protection, CI/CD pipeline security, and incident response.

Each point in this checklist is a critical pillar in building a defense-in-depth strategy that is both robust and scalable. The goal is to provide a comprehensive framework that enables your team to innovate securely without slowing down development cycles. For a broader view of organizational security posture, considering an ultimate 10-point cyber security audit checklist can offer valuable insights into foundational controls. However, this guide focuses specifically on the technical implementation details required to secure modern cloud-native architectures, ensuring your infrastructure is resilient by design.

1. Identity and Access Management (IAM) Configuration

Implementing a robust Identity and Access Management (IAM) strategy is the cornerstone of any effective cloud security checklist. At its core, IAM governs who (users, services, applications) can do what (read, write, delete) to which resources (databases, storage buckets, virtual machines). A misconfigured IAM policy can instantly create a critical vulnerability, making it a non-negotiable first step.

The primary goal is to enforce the Principle of Least Privilege (PoLP). This security concept dictates that every user, system, or application should only have the absolute minimum permissions required to perform its designated function. This drastically reduces the potential blast radius of a compromised account or service. Instead of granting broad administrative rights, you create granular, purpose-built roles that limit access strictly to what is necessary.

Why It's Foundational

IAM is the control plane for your entire cloud environment. Without precise control over access, other security measures like network firewalls or encryption become significantly less effective. A malicious actor with overly permissive credentials can simply bypass other defenses. Proper IAM configuration prevents unauthorized access, lateral movement, and data exfiltration by ensuring every action is authenticated and explicitly authorized.

Implementation Examples and Actionable Tips

To effectively manage identities and permissions, DevOps and engineering teams should focus on automation, auditing, and granular control.

-

Automate IAM with Infrastructure-as-Code (IaC): Define all IAM roles, policies, and user assignments in code using tools like Terraform or AWS CloudFormation. This approach provides an auditable, version-controlled history of all permission changes and prevents manual configuration drift.

- Example (Terraform): Create a specific IAM policy for an S3 bucket allowing only

s3:GetObjectands3:ListBucketactions, then attach it to a role assumed by your application servers.

- Example (Terraform): Create a specific IAM policy for an S3 bucket allowing only

-

Embrace Role-Based Access Control (RBAC): Create distinct roles for different functions, such as

ci-cd-deployer,database-admin, orapplication-server-role. Avoid assigning permissions directly to individual users.- Tip: In AWS, use cross-account IAM roles with a unique

ExternalIdcondition to prevent the "confused deputy" problem when granting third-party services access to your environment.

- Tip: In AWS, use cross-account IAM roles with a unique

-

Enforce Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) Universally: MFA is one of the most effective controls for preventing account takeovers. Mandate its use for all human users, especially those with access to production environments or sensitive data.

- Example: Configure an AWS IAM policy with the condition

{"Bool": {"aws:MultiFactorAuthPresent": "true"}}on sensitive administrator roles to deny any action taken without an active MFA session.

- Example: Configure an AWS IAM policy with the condition

-

Use Temporary Credentials for Services: Never embed static, long-lived API keys or secrets in application code or configuration files. Instead, leverage instance profiles (AWS EC2), workload identity federation (Google Cloud), or managed identities (Azure) to grant services temporary, automatically-rotated credentials.

- Action: For Kubernetes clusters on AWS (EKS), implement IAM Roles for Service Accounts (IRSA) to associate IAM roles directly with Kubernetes service accounts, providing fine-grained permissions to pods.

2. Network Security and Segmentation

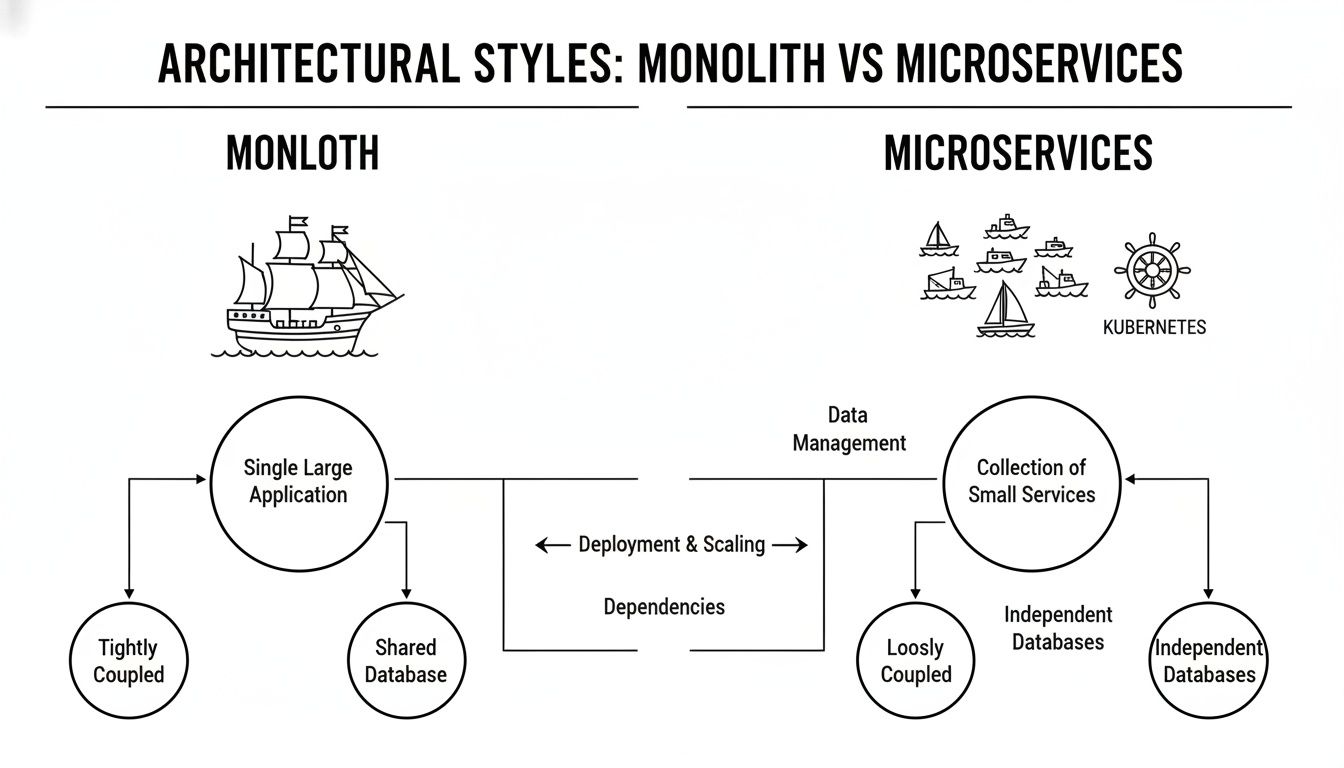

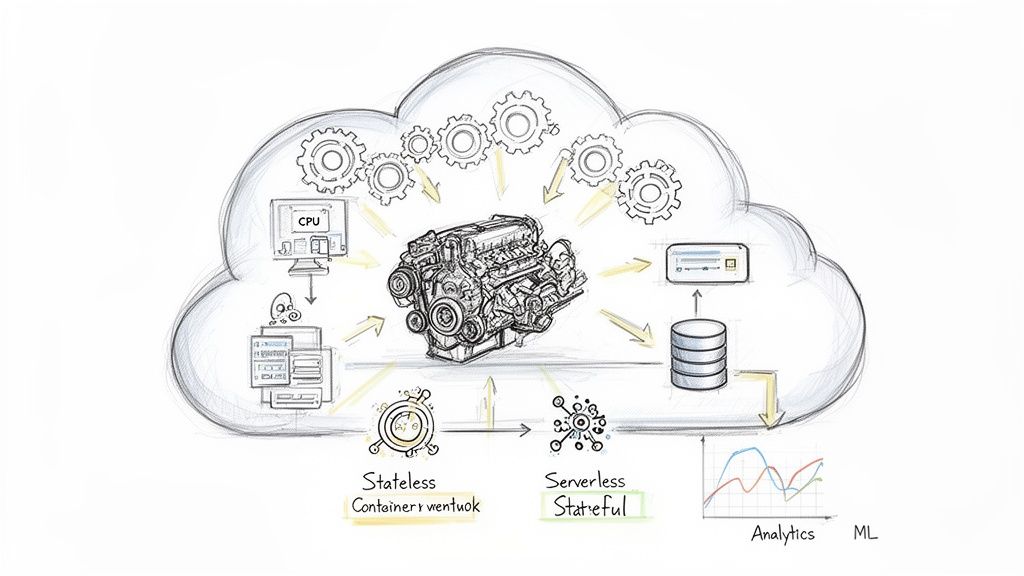

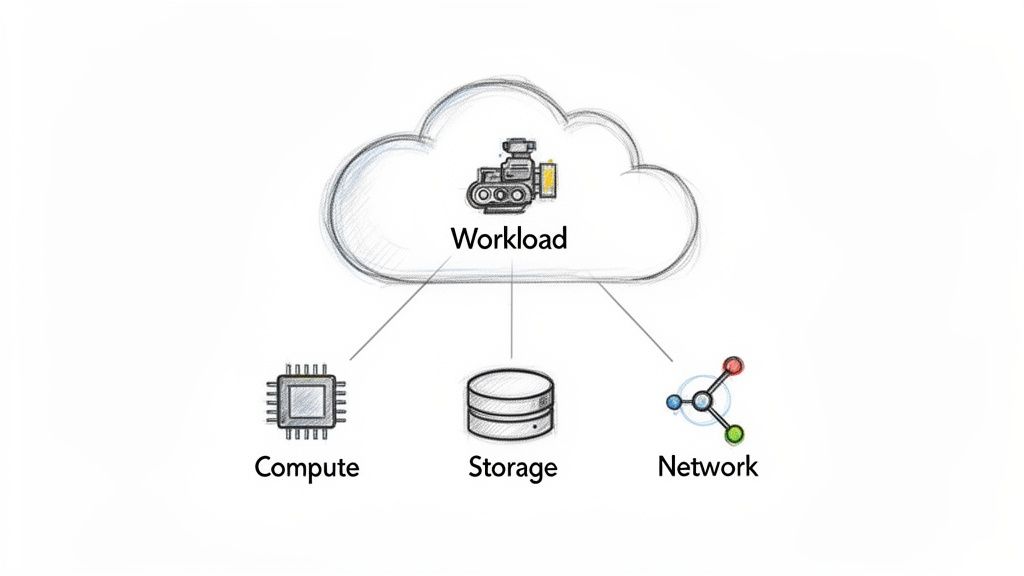

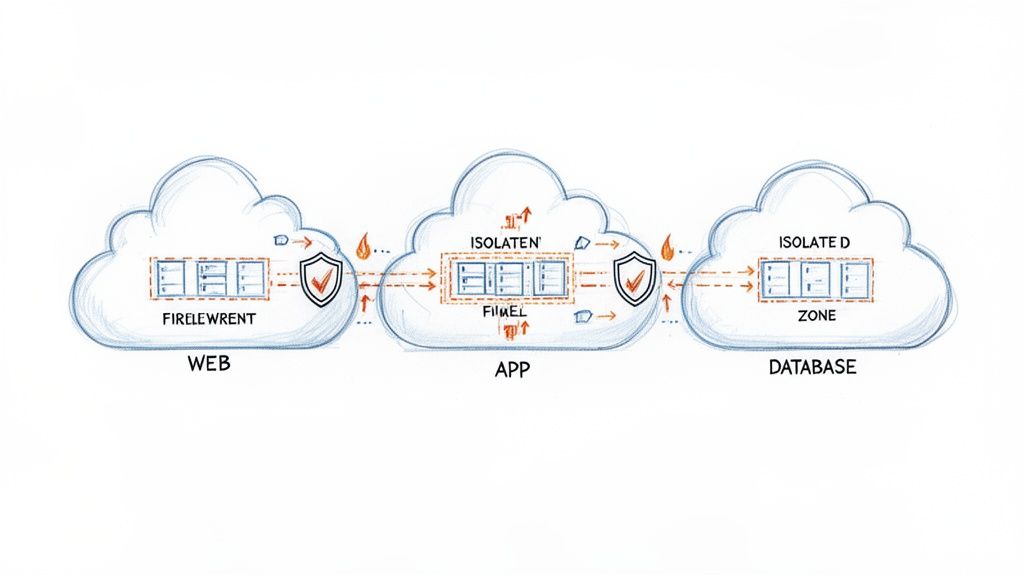

After establishing who can access what, the next critical layer in a cloud security checklist is controlling how resources communicate with each other and the outside world. Network security and segmentation involve architecting your cloud environment into isolated security zones using Virtual Private Clouds (VPCs), subnets, and firewalls. This strategy is foundational to a defense-in-depth approach.

The core objective is to limit an attacker's ability to move laterally across your infrastructure. By dividing the network into distinct segments, such as a public-facing web tier, a protected application tier, and a highly restricted database tier, you ensure that a compromise in one zone does not automatically grant access to another. This containment drastically minimizes the potential impact of a breach.

Why It's Foundational

Proper network segmentation acts as the internal enforcement boundary within your cloud environment. While IAM controls access to resources, network controls govern the communication pathways between them. A well-segmented network prevents a compromised web server from directly accessing a sensitive production database, even if the attacker manages to steal credentials. This layer of isolation is essential for protecting critical data and meeting compliance requirements like PCI DSS.

Implementation Examples and Actionable Tips

Effective network security relies on codified rules, proactive monitoring, and a zero-trust mindset where no traffic is trusted by default.

-

Define Network Boundaries with Infrastructure-as-Code (IaC): Use tools like Terraform or CloudFormation to declaratively define your VPCs, subnets, route tables, and firewall rules (e.g., AWS Security Groups, Azure Network Security Groups). This ensures your network topology is versioned, auditable, and easily replicated across environments.

- Example: A Terraform module defines an AWS VPC with separate public subnets for load balancers and private subnets for application servers, where security groups only allow traffic from the load balancer to the application on port 443.

-

Implement Microsegmentation for Granular Control: For containerized workloads, use service meshes like Istio or Linkerd, or native Kubernetes Network Policies. These tools enforce traffic rules at the individual service (pod) level, preventing unauthorized communication even within the same subnet.

- Action: Create a default-deny Kubernetes Network Policy that blocks all pod-to-pod traffic within a namespace, then add explicit "allow" policies for required communication paths. Use YAML definitions to specify

podSelectorandingress/egressrules.

- Action: Create a default-deny Kubernetes Network Policy that blocks all pod-to-pod traffic within a namespace, then add explicit "allow" policies for required communication paths. Use YAML definitions to specify

-

Log and Analyze Network Traffic: Enable flow logs (e.g., AWS VPC Flow Logs, Google Cloud VPC Flow Logs) and forward them to a SIEM tool. This provides critical visibility into all network traffic, helping you detect anomalous patterns, identify misconfigurations, or investigate security incidents.

- Example: Use AWS Athena to query VPC Flow Logs stored in S3 to identify all traffic that was rejected by a security group over the last 24 hours, helping you troubleshoot or detect unauthorized connection attempts.

-

Secure Ingress and Egress Points: Protect public-facing applications with a Web Application Firewall (WAF) to filter malicious traffic like SQL injection and XSS. For outbound traffic, use private endpoints and bastion hosts (jump boxes) for administrative access instead of assigning public IPs to sensitive resources.

- Action: Use AWS Systems Manager Session Manager instead of a traditional bastion host to provide secure, auditable shell access to EC2 instances without opening any inbound SSH ports in your security groups.

3. Encryption in Transit and at Rest

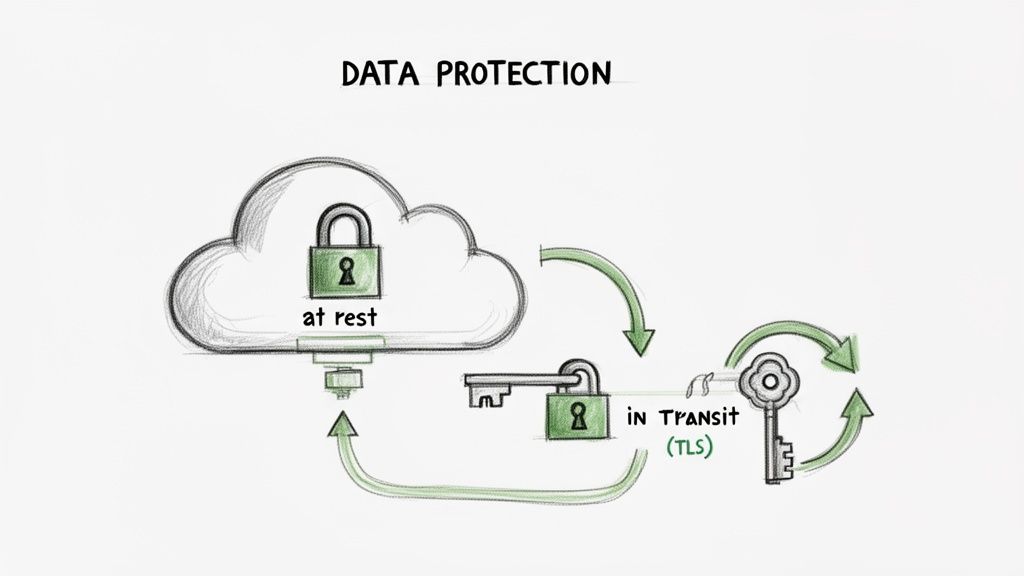

Encrypting data is a non-negotiable layer of defense that protects information from unauthorized access, both when it is stored and while it is moving. Encryption in transit secures data as it travels across networks (e.g., from a user to a web server), while encryption at rest protects data stored in databases, object storage, and backups. A comprehensive encryption strategy is a fundamental part of any cloud security checklist, rendering data unreadable and unusable to anyone without the proper decryption keys.

The primary goal is to ensure that even if an attacker bypasses other security controls and gains access to the underlying storage or network traffic, the data itself remains confidential and protected. Modern cloud providers offer robust, managed services that simplify the implementation of encryption, making it accessible and manageable at scale.

Why It's Foundational

Encryption serves as the last line of defense for your data. If IAM policies fail or a network vulnerability is exploited, strong encryption ensures that the compromised data is worthless without the keys. This control is critical for meeting regulatory compliance mandates like GDPR, HIPAA, and PCI DSS, which explicitly require data protection. It directly mitigates the risk of data breaches, protecting customer trust and intellectual property.

Implementation Examples and Actionable Tips

Effective data protection requires a combination of strong cryptographic standards, secure key management, and consistent policy enforcement across all cloud resources.

-

Enforce TLS 1.2+ for All In-Transit Data: Configure load balancers, CDNs, and API gateways to reject older, insecure protocols like SSL and early TLS versions. Use services like Let's Encrypt for automated certificate management.

- Example: In AWS, attach an ACM (AWS Certificate Manager) certificate to an Application Load Balancer and define a security policy like

ELBSecurityPolicy-TLS-1-2-2017-01to enforce modern cipher suites. Use CloudFront'sViewerProtocolPolicyset toredirect-to-httpsto enforce encryption between clients and the CDN.

- Example: In AWS, attach an ACM (AWS Certificate Manager) certificate to an Application Load Balancer and define a security policy like

-

Use Customer-Managed Encryption Keys (CMEK) for Sensitive Data: While cloud providers offer default encryption, CMEK gives you direct control over the key lifecycle, including creation, rotation, and revocation. This is crucial for demonstrating compliance and control.

- Action: Use AWS Key Management Service (KMS) to create a customer-managed key and define a key policy that restricts its usage to specific IAM roles or services. Use this key to encrypt your RDS databases and S3 buckets.

-

Automate Key Rotation and Auditing: Regularly rotating encryption keys limits the time window an attacker has if a key is compromised. Configure key management services to rotate keys automatically, typically on an annual basis.

- Example: Enable automatic key rotation for a customer-managed key in Google Cloud KMS. This creates a new key version annually while keeping old versions available to decrypt existing data. Audit key usage via CloudTrail or Cloud Audit Logs.

-

Integrate a Dedicated Secrets Management System: Never hardcode secrets like database credentials or API keys. Use a centralized secrets manager like HashiCorp Vault or AWS Secrets Manager to store, encrypt, and tightly control access to this sensitive information.

- Action: For Kubernetes, deploy the Secrets Store CSI driver to mount secrets from AWS Secrets Manager or Azure Key Vault directly into pods as volumes, avoiding the need to store them as native Kubernetes secrets.

4. Cloud Infrastructure Compliance and Configuration Management

Manual infrastructure provisioning is a direct path to security vulnerabilities and operational chaos. Effective configuration management ensures that cloud resources are deployed consistently and securely according to predefined organizational standards. This practice relies on Infrastructure-as-Code (IaC), configuration drift detection, and automated compliance scanning to maintain a secure and predictable environment.

The core objective is to create a single source of truth for your infrastructure's desired state, typically stored in a version control system like Git. This approach codifies your architecture, making changes auditable, repeatable, and less prone to human error. By managing infrastructure programmatically, you prevent "configuration drift" where manual, undocumented changes erode your security posture over time. This item is a critical part of any comprehensive cloud security checklist because it shifts security left, catching issues before they reach production.

Why It's Foundational

Misconfigured cloud services are a leading cause of data breaches. A robust configuration management strategy provides persistent visibility into your infrastructure's state and enforces security baselines automatically. This prevents the deployment of non-compliant resources, such as publicly exposed storage buckets or virtual machines with unrestricted network access. It transforms security from a reactive, manual audit process into a proactive, automated guardrail integrated directly into your development lifecycle.

Implementation Examples and Actionable Tips

To build a resilient and compliant infrastructure, engineering teams should codify everything, automate validation, and actively monitor for deviations.

-

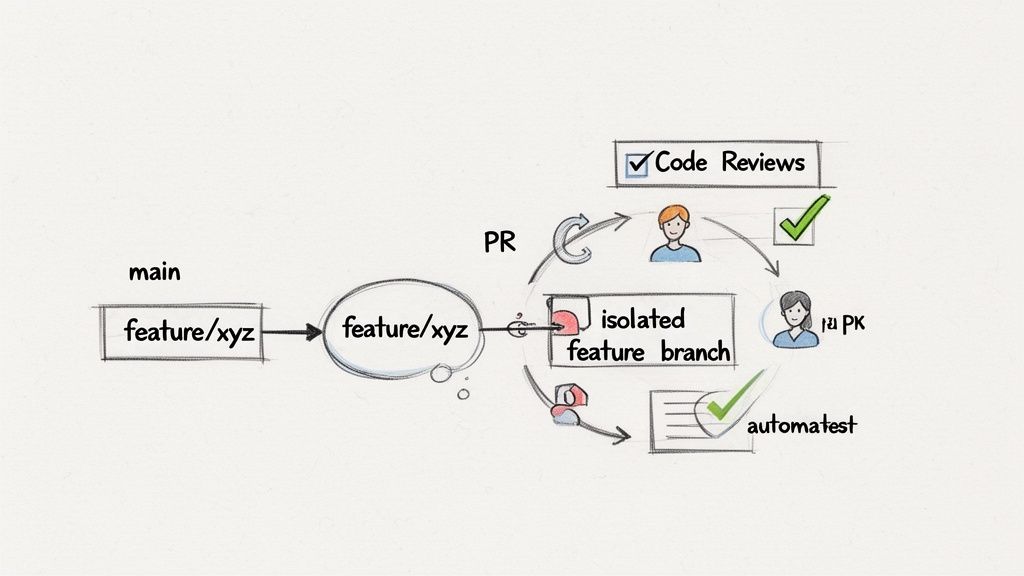

Codify Everything with Infrastructure-as-Code (IaC): Define all cloud resources using tools like Terraform, AWS CloudFormation, or Pulumi. Store these definitions in Git and protect the

mainbranch with mandatory peer reviews for all changes.- Action: Use remote state backends like Amazon S3 with DynamoDB locking or Terraform Cloud. This prevents concurrent modifications and state file corruption, which is critical for team collaboration.

-

Implement Policy-as-Code (PaC) for Prevention: Use tools like Open Policy Agent (OPA) or Sentinel (in Terraform Cloud) to create and enforce rules during the deployment pipeline. These policies can prevent non-compliant infrastructure from ever being provisioned.

- Example: Write a Sentinel policy that rejects any Terraform plan attempting to create an AWS security group with an inbound rule allowing SSH access (

port 22) from any IP address (0.0.0.0/0).

- Example: Write a Sentinel policy that rejects any Terraform plan attempting to create an AWS security group with an inbound rule allowing SSH access (

-

Scan IaC in Your CI/CD Pipeline: Integrate static analysis security testing (SAST) tools like Checkov or tfsec directly into your CI/CD workflow. These tools scan your Terraform or CloudFormation code for thousands of known misconfigurations before deployment. For more information on meeting industry standards, learn more about SOC 2 compliance requirements.

-

Tag Resources and Detect Drift: Automatically tag all resources with critical metadata (e.g.,

owner,environment,cost-center) for better governance. To optimize costs and ensure compliance, adopting robust IT Asset Management best practices is essential for mastering the complete lifecycle of your IT assets. Use services like AWS Config or Azure Policy to continuously monitor for and automatically remediate configuration drift from your defined baseline.

5. Logging, Monitoring, and Alerting

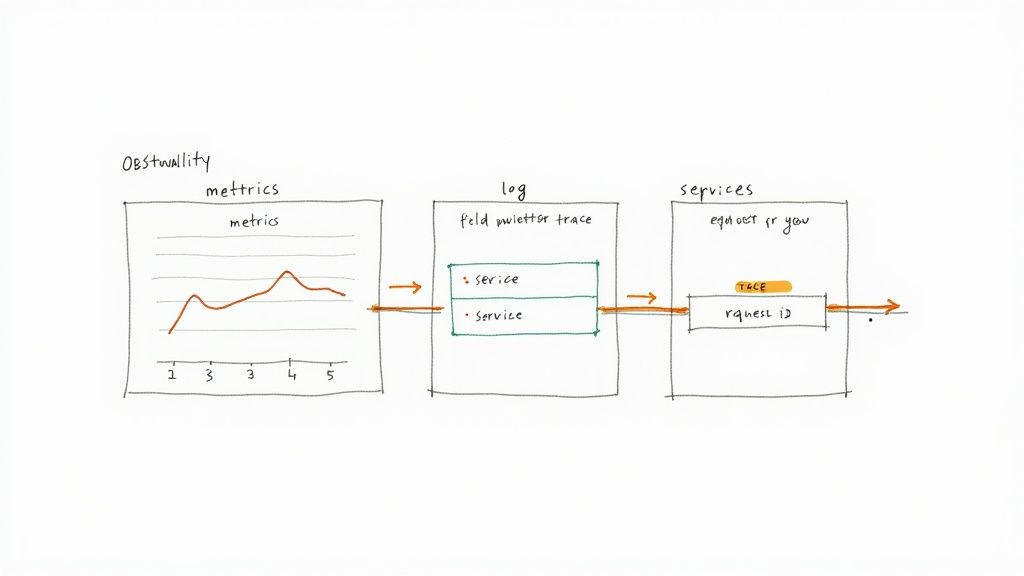

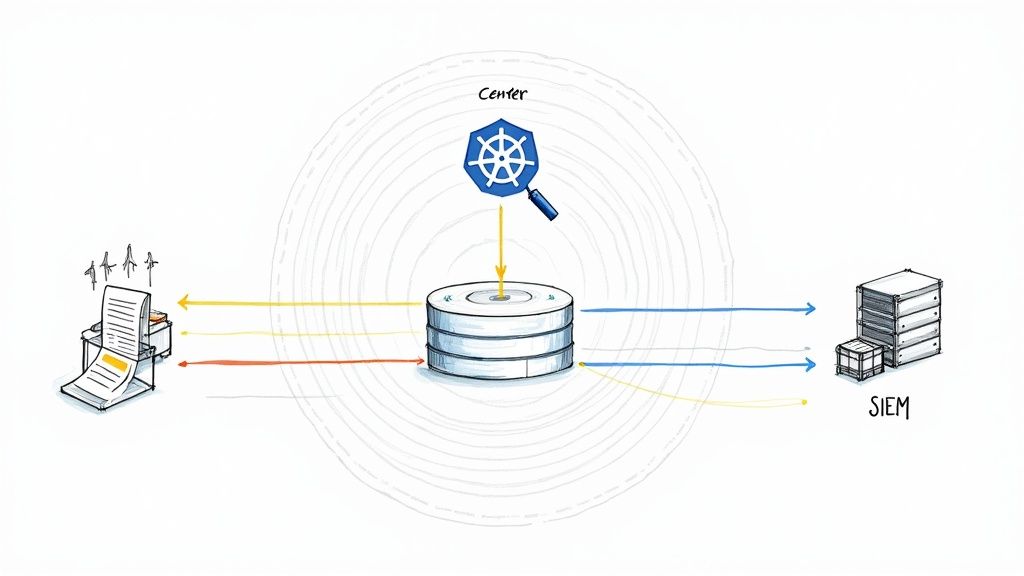

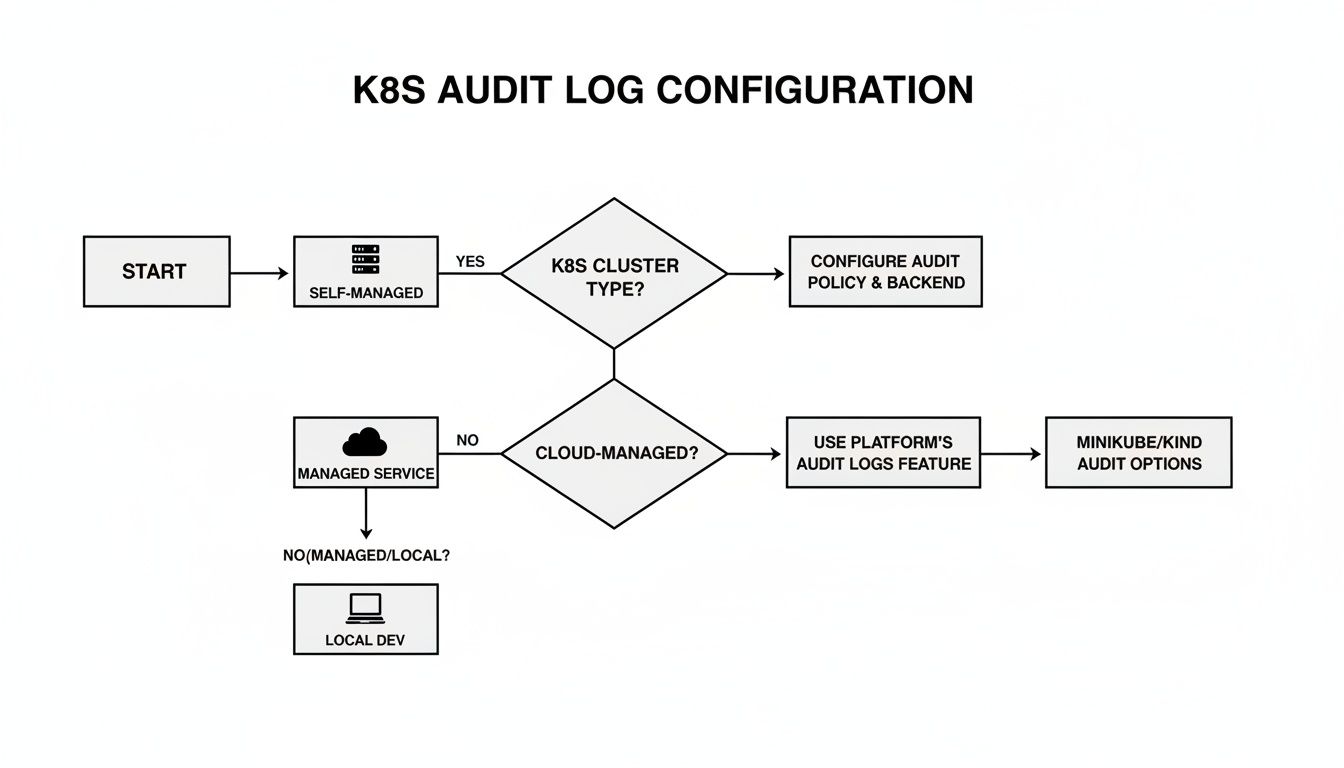

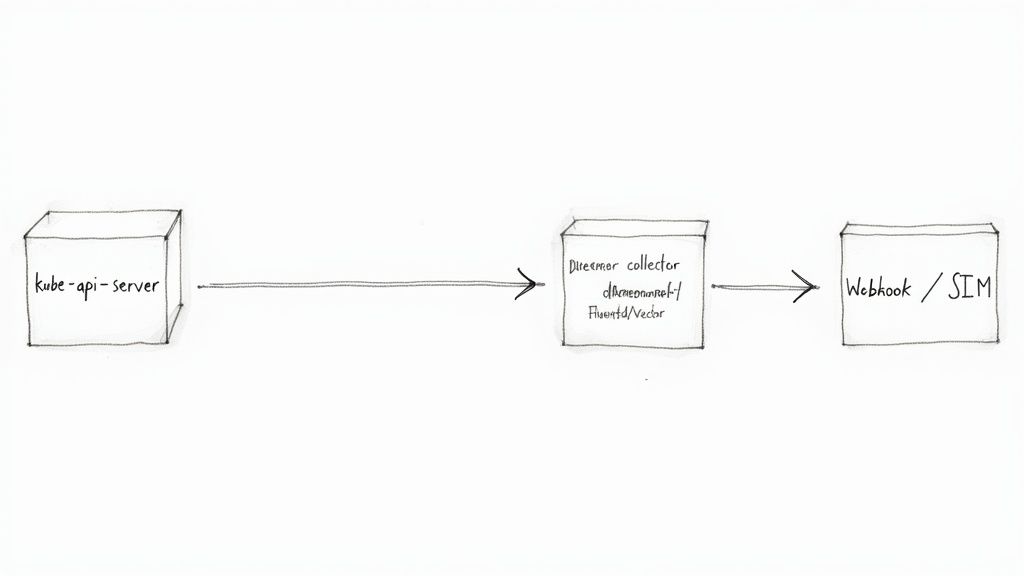

Comprehensive logging, monitoring, and alerting form the central nervous system of your cloud security posture. This practice involves systematically collecting, aggregating, and analyzing activity data from your entire cloud infrastructure. Without it, you are effectively operating blind, unable to detect unauthorized access, system anomalies, or active security incidents.

The goal is to create a complete, queryable audit trail of all actions and events. This visibility enables proactive threat detection, accelerates incident response, and provides the forensic evidence needed for post-mortem analysis and compliance audits. An effective logging strategy transforms a flood of raw event data into actionable security intelligence, making it an indispensable part of any cloud security checklist.

Why It's Foundational

You cannot protect what you cannot see. Logging and monitoring provide the necessary visibility to validate that other security controls are working as expected. If an IAM policy is violated or a network firewall is breached, robust logs are the only way to detect and respond to the event in a timely manner. This continuous oversight is critical for identifying suspicious behavior, understanding the scope of an incident, and preventing minor issues from escalating into major breaches.

Implementation Examples and Actionable Tips

To build a powerful monitoring and alerting pipeline, engineering teams must focus on centralization, automation, and structured data analysis.

-

Centralize All Logs in a Secure Account: Aggregate logs from all sources (e.g., AWS CloudTrail, VPC Flow Logs, application logs) into a single, dedicated logging account. This account should have highly restrictive access policies to ensure log integrity.

- Example: Use AWS Control Tower to set up a dedicated "Log Archive" account and configure CloudTrail at the organization level to deliver all management event logs to a centralized, immutable S3 bucket within that account.

-

Implement Structured Logging: Configure your applications to output logs in a machine-readable format like JSON. Structured logs are far easier to parse, query, and index than plain text, enabling more powerful and efficient analysis.

- Action: Use libraries like Logback (Java) or Winston (Node.js) to automatically format log output as JSON, including contextual data like

trace_idanduser_idfor better correlation.

- Action: Use libraries like Logback (Java) or Winston (Node.js) to automatically format log output as JSON, including contextual data like

-

Create High-Fidelity, Automated Alerts: Define specific alert rules for critical security events, such as root user API calls, IAM policy changes, or security group modifications. Integrate these alerts with incident management tools to automate response workflows.

- Example: Set up an AWS EventBridge rule that listens for the CloudTrail event

ConsoleLoginwith auserIdentity.typeofRoot. Configure this rule to trigger an SNS topic that sends a critical notification to your security team and PagerDuty.

- Example: Set up an AWS EventBridge rule that listens for the CloudTrail event

-

Develop Context-Rich Dashboards: Build dashboards tailored to different audiences (Security, Operations, Leadership) to visualize key security metrics and trends. A well-designed dashboard can surface anomalies that might otherwise go unnoticed.

- Action: Use OpenSearch Dashboards (or Grafana) to create a security dashboard that visualizes GuardDuty findings by severity, maps rejected network traffic from VPC Flow Logs, and charts IAM access key age to identify old credentials.

6. Data Backup and Disaster Recovery

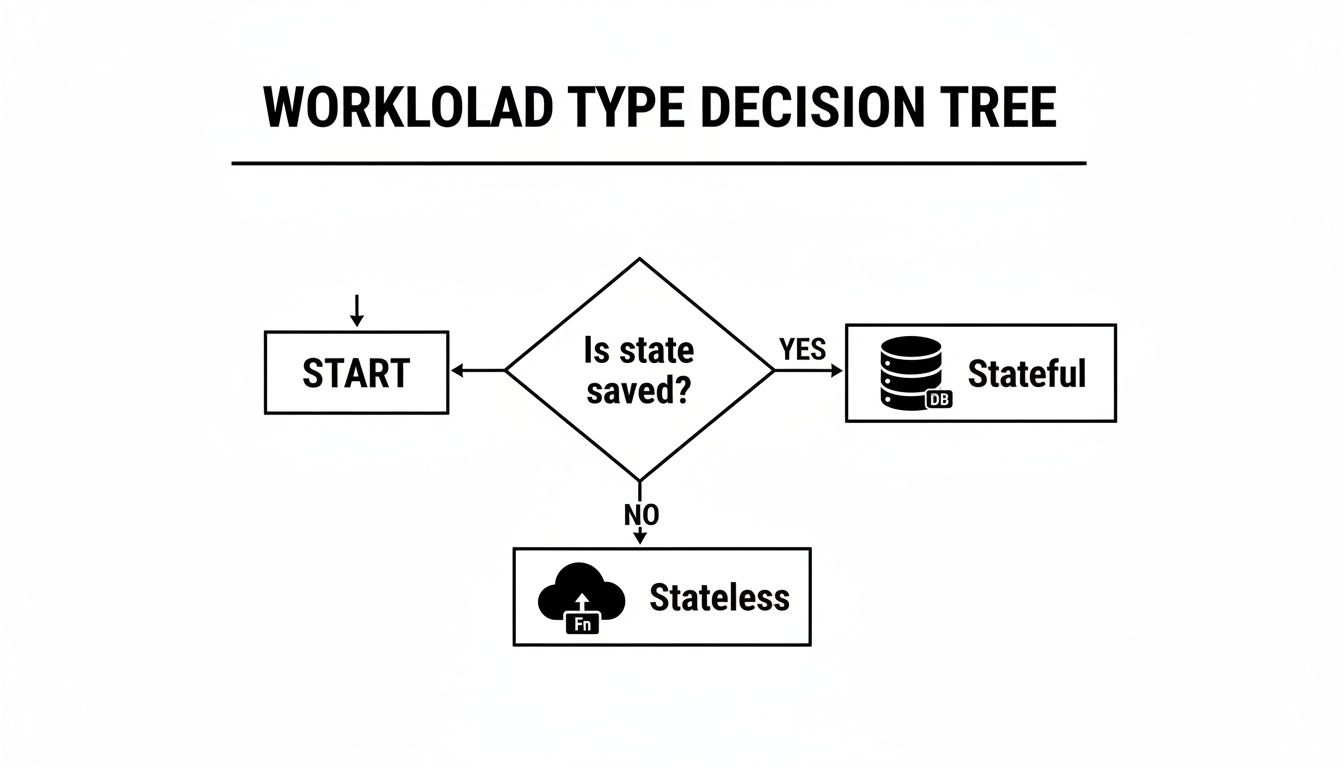

Implementing comprehensive data backup and disaster recovery (DR) controls is essential for business continuity and operational resilience. This practice ensures you can recover from data loss caused by accidental deletion, corruption, ransomware attacks, or catastrophic system failures. It involves creating regular, automated backups of critical data and systems, paired with tested procedures to restore them quickly and reliably.

The primary goal is to meet predefined Recovery Time Objectives (RTO) and Recovery Point Objectives (RPO). RTO defines the maximum acceptable downtime following a disaster, while RPO specifies the maximum acceptable amount of data loss. A well-designed backup strategy, a critical part of any cloud security checklist, is your last line of defense against destructive attacks and ensures your business can survive a major incident.

Why It's Foundational

While other controls focus on preventing breaches, backup and DR strategies focus on recovery after an incident has occurred. In the age of sophisticated ransomware that can encrypt entire production environments, a robust and isolated backup system is often the only viable path to restoration without paying a ransom. It guarantees that even if your primary systems are compromised, your data remains safe and recoverable, protecting revenue, reputation, and customer trust.

Implementation Examples and Actionable Tips

To build a resilient DR plan, engineering teams should prioritize automation, regular testing, and immutability.

-

Centralize and Automate Backups: Use cloud-native services like AWS Backup, Azure Backup, or Google Cloud Backup and Disaster Recovery to create centralized, policy-driven backup plans. These tools can automatically manage backups across various services like databases, file systems, and virtual machines.

- Example: Configure an AWS Backup plan that takes daily snapshots of all RDS instances tagged with

environment=productionand stores them for 30 days, with monthly backups moved to cold storage for long-term archival.

- Example: Configure an AWS Backup plan that takes daily snapshots of all RDS instances tagged with

-

Test Restoration Procedures Relentlessly: Backups are useless if they cannot be restored. Schedule and automate quarterly or bi-annual DR tests where you restore systems and data into an isolated environment to validate the integrity of backups and the accuracy of your runbooks.

- Action: Automate the DR test using a Lambda function or Step Function that programmatically restores the latest RDS snapshot to a new instance, verifies database connectivity, and then tears down the test environment, reporting the results.

-

Implement Immutable Backups: To defend against ransomware, ensure your backups cannot be altered or deleted, even by an account with administrative privileges. Use features like AWS S3 Object Lock in Compliance Mode or Veeam's immutable repositories.

- Example: Store critical database backups in an S3 bucket with Object Lock enabled. This prevents the backup files from being encrypted or deleted by a malicious actor who has compromised your primary cloud account.

-

Ensure Geographic Redundancy: Replicate backups to a separate geographic region to protect against region-wide outages or disasters. Most cloud providers offer built-in cross-region replication for their storage and backup services.

- Action: For Kubernetes, use a tool like Velero to back up application state and configuration to an S3 bucket, then configure Cross-Region Replication (CRR) on that bucket to automatically copy the backups to a DR region.

7. Vulnerability Management and Patch Management

Effective vulnerability management is a continuous, proactive process for identifying, evaluating, and remediating security weaknesses across your entire cloud footprint. This involves everything from container images and application dependencies to the underlying cloud infrastructure. Failing to manage vulnerabilities is like leaving a door unlocked; it provides a direct path for attackers to exploit known weaknesses, making this a critical part of any comprehensive cloud security checklist.

The core objective is to systematically reduce your attack surface. By integrating automated scanning and disciplined patching, you can discover and fix security flaws before they can be exploited. This process encompasses regular security scans, dependency analysis, and the timely application of patches to mitigate identified risks, ensuring the integrity and security of your production environment.

Why It's Foundational

Vulnerabilities are an inevitable part of software development. New exploits for existing libraries and operating systems are discovered daily. Without a robust vulnerability management program, your cloud environment becomes increasingly fragile and exposed over time. This control is foundational because it directly prevents common attack vectors and hardens your applications and infrastructure against widespread, automated exploits that target known Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVEs).

Implementation Examples and Actionable Tips

To build a mature vulnerability management process, engineering and security teams must prioritize automation, integration into the development lifecycle, and risk-based prioritization.

-

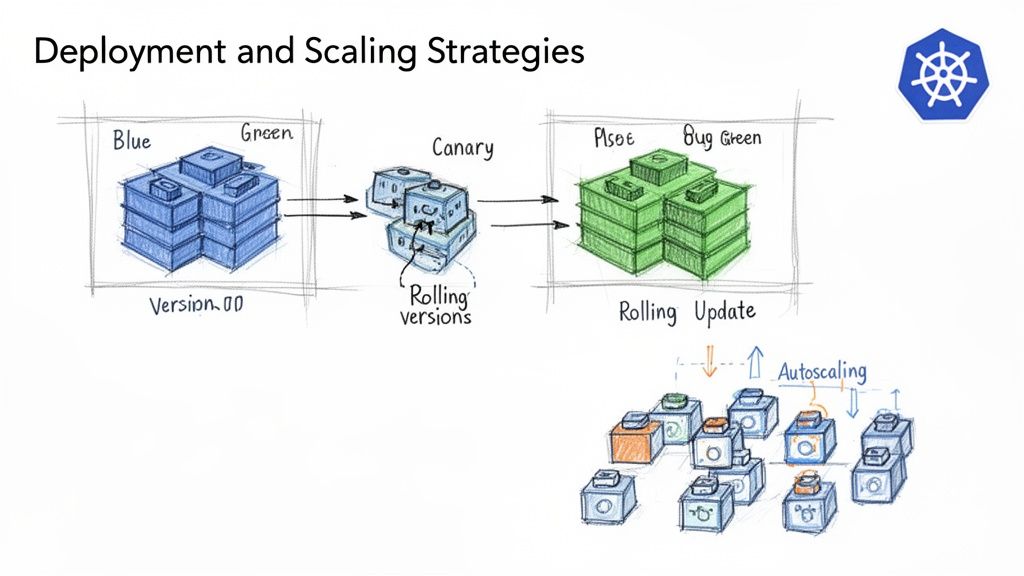

Integrate Scanning into the CI/CD Pipeline: Shift security left by embedding vulnerability scanners directly into your build and deploy pipelines. Use tools like Snyk or Trivy to scan application dependencies, container images, and Infrastructure-as-Code (IaC) configurations on every commit.

- Example: Configure a GitHub Actions workflow that runs a Trivy scan on a Docker image during the build step. The workflow should fail the build if any vulnerabilities with a

CRITICALorHIGHseverity are discovered, preventing the vulnerable artifact from being pushed to a registry.

- Example: Configure a GitHub Actions workflow that runs a Trivy scan on a Docker image during the build step. The workflow should fail the build if any vulnerabilities with a

-

Maintain a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM): An SBOM provides a complete inventory of all components and libraries within your software. This visibility is crucial for quickly identifying whether your systems are affected when a new zero-day vulnerability is disclosed.

- Action: Use tools like Syft to automatically generate an SBOM for your container images and applications during the build process, and store it alongside the artifact. Ingest the SBOM into a dependency tracking tool to get alerts on newly discovered vulnerabilities.

-

Prioritize Patching Based on Risk, Not Just Score: A high CVSS score doesn't always translate to high risk in your specific environment. Prioritize vulnerabilities that are actively exploited in the wild, have a known public exploit, or affect mission-critical, internet-facing services.

- Example: Use a tool like AWS Inspector, which provides an exploitability score alongside the CVSS score, to help prioritize patching efforts on your EC2 instances. A vulnerability with a lower CVSS but a high exploitability score might be a higher priority than one with a perfect CVSS 10.0 that requires complex local access to exploit.

-

Automate Patching for Controlled Environments: For development and staging environments, implement automated patching for operating systems and routine software updates. This reduces the manual workload and ensures a consistent baseline security posture.

- Action: Use AWS Systems Manager Patch Manager with a defined patch baseline (e.g., auto-approve critical patches 7 days after release) and schedule automated patching during a maintenance window for your EC2 fleets.

8. Secrets Management and Rotation

Effective secrets management is a critical component of a modern cloud security checklist, addressing the secure storage, access, and lifecycle of sensitive credentials. Secrets include API keys, database passwords, and TLS certificates. Hardcoding these credentials directly into application code, configuration files, or CI/CD pipelines creates a massive security risk, making them easily discoverable by unauthorized individuals or leaked through version control systems.

The core principle is to centralize secrets in a dedicated, hardened system often called a "vault." This system provides programmatic access to secrets at runtime, ensuring applications only receive the credentials they need, when they need them. It also enables robust auditing, access control, and, most importantly, automated rotation, which systematically invalidates old credentials and issues new ones without manual intervention.

Why It's Foundational

Compromised credentials are one of the most common attack vectors leading to major data breaches. A robust secrets management strategy directly mitigates this risk by treating secrets as ephemeral, dynamically-generated assets rather than static, long-lived liabilities. By decoupling secrets from code and infrastructure, you enhance security posture, simplify credential updates, and ensure developers never need to handle sensitive information directly, reducing the chance of accidental exposure.

Implementation Examples and Actionable Tips

To build a secure and scalable secrets management workflow, engineering teams should prioritize automation, dynamic credentials, and strict access controls.

-

Utilize a Dedicated Secrets Management Tool: Adopt a specialized solution like HashiCorp Vault, AWS Secrets Manager, Azure Key Vault, or Google Cloud Secret Manager. These tools provide APIs for secure secret retrieval, fine-grained access policies, and audit logging.

- Example: Configure AWS Secrets Manager to automatically rotate an RDS database password every 30 days using a built-in Lambda rotation function. The application retrieves the current password at startup by querying the Secrets Manager API via its IAM role, eliminating hardcoded credentials.

-

Implement Automatic Rotation and Short-Lived Credentials: The goal is to minimize the lifespan of any given secret. Configure your secrets manager to automatically rotate credentials on a regular schedule. For maximum security, use dynamic secrets that are generated on-demand for a specific task and expire shortly after.

- Action: Use HashiCorp Vault's database secrets engine to generate unique, time-limited database credentials for each application instance. The application authenticates to Vault, requests a credential, uses it, and the credential automatically expires and is revoked.

-

Prevent Secrets in Version Control: Never commit secrets to Git or any other version control system. Use pre-commit hooks and repository scanning tools like

git-secretsor TruffleHog to detect and block accidental commits of sensitive data.- Example: Integrate a secret scanning step using a tool like Gitleaks into your CI pipeline that fails the build if any secrets are detected in the codebase, preventing them from being merged into the main branch.

-

Audit All Secret Access: Centralized secrets management provides a clear audit trail. Monitor all

readandlistoperations on your secrets, and configure alerts for anomalous activity, such as access from an unexpected IP address or an unusual number of access requests. Discover more by reviewing these secrets management best practices on opsmoon.com.

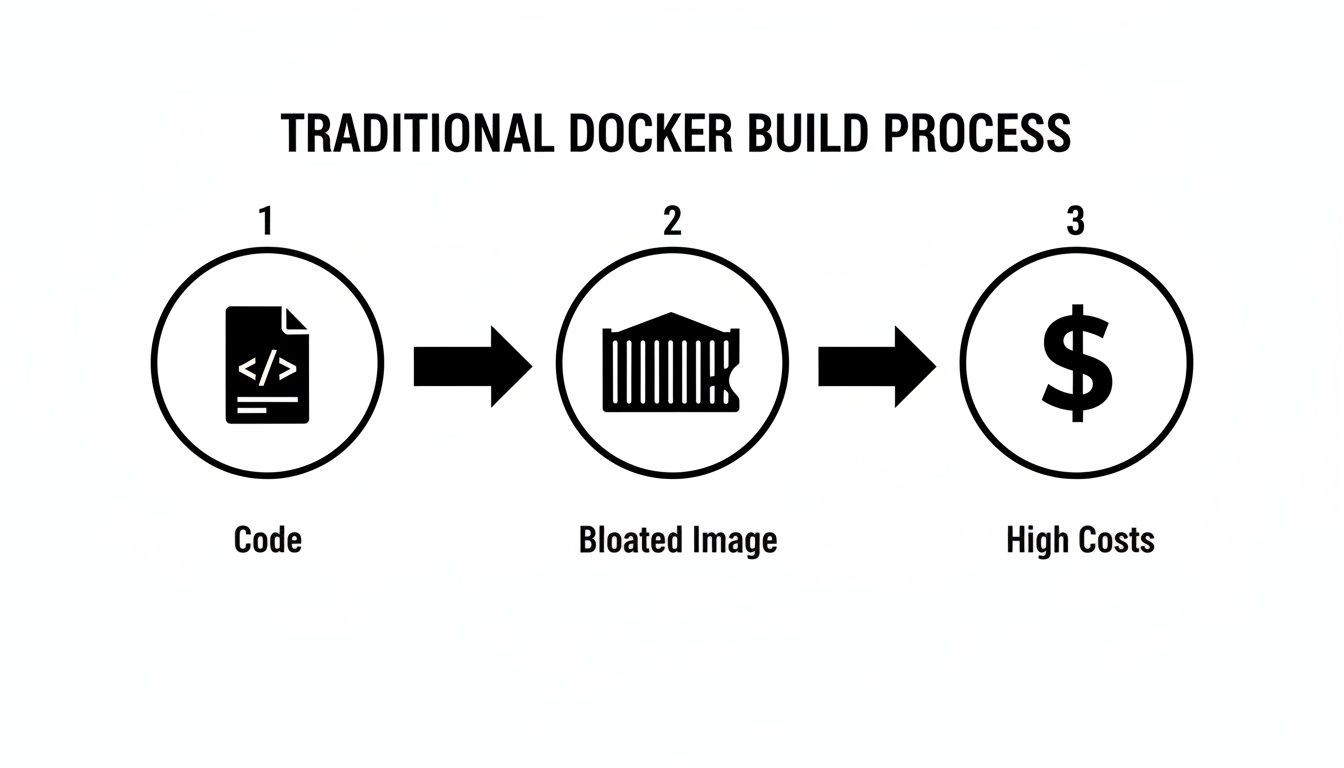

9. Container and Container Registry Security

Securing the container lifecycle is a non-negotiable part of any modern cloud security checklist. This practice addresses risks from the moment a container image is built to its deployment and runtime execution. It involves scanning images for vulnerabilities, controlling access to container registries, and enforcing runtime security policies to protect containerized applications from threats.

The primary goal is to establish a secure software supply chain and a hardened runtime environment. This means ensuring that only trusted, vulnerability-free images are deployed and that running containers operate within strictly defined security boundaries. A compromised container can provide a foothold for an attacker to move laterally across your cloud infrastructure, making this a critical defense layer, especially in Kubernetes-orchestrated environments.

Why It's Foundational

Containers package an application with all its dependencies, creating a consistent but potentially opaque attack surface. Without dedicated security controls, vulnerable libraries or misconfigurations can be bundled directly into your production workloads. Securing the container pipeline ensures that what you build is what you safely run, preventing the deployment of known exploits and limiting the blast radius of any runtime security incidents.

Implementation Examples and Actionable Tips

To effectively secure your container ecosystem, engineering and DevOps teams must integrate security checks throughout the entire lifecycle, from code commit to runtime monitoring.

-

Automate Vulnerability Scanning in CI/CD: Integrate open-source scanners like Trivy or commercial tools directly into your continuous integration pipeline. This automatically scans base images and application dependencies for known vulnerabilities before an image is ever pushed to a registry.

- Example: In a GitLab CI/CD pipeline, add a stage that uses Trivy to scan the newly built Docker image and outputs the results as a JUnit XML report. Configure the job to fail if vulnerabilities exceed a defined threshold (e.g.,

--severity CRITICAL,HIGH).

- Example: In a GitLab CI/CD pipeline, add a stage that uses Trivy to scan the newly built Docker image and outputs the results as a JUnit XML report. Configure the job to fail if vulnerabilities exceed a defined threshold (e.g.,

-

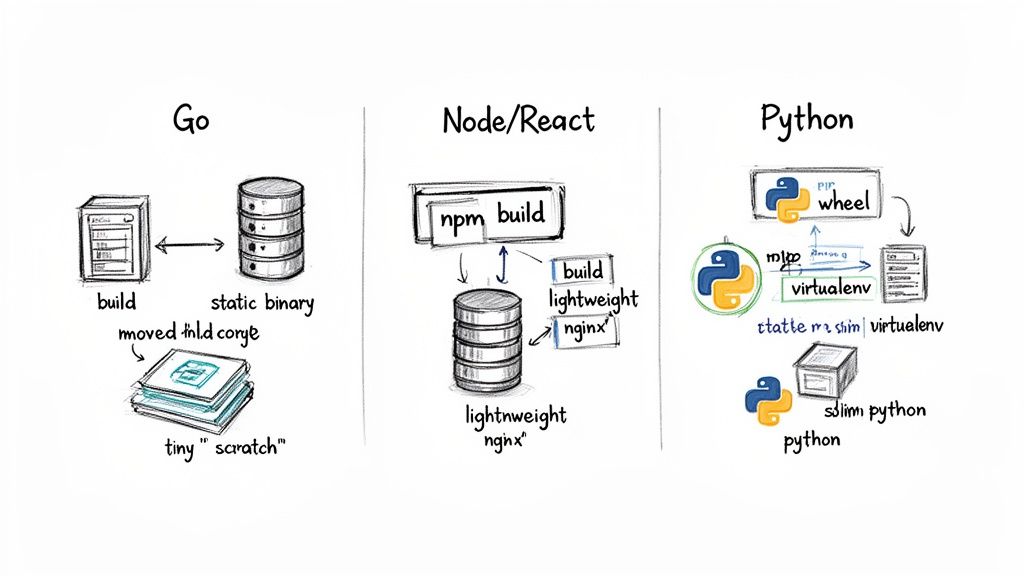

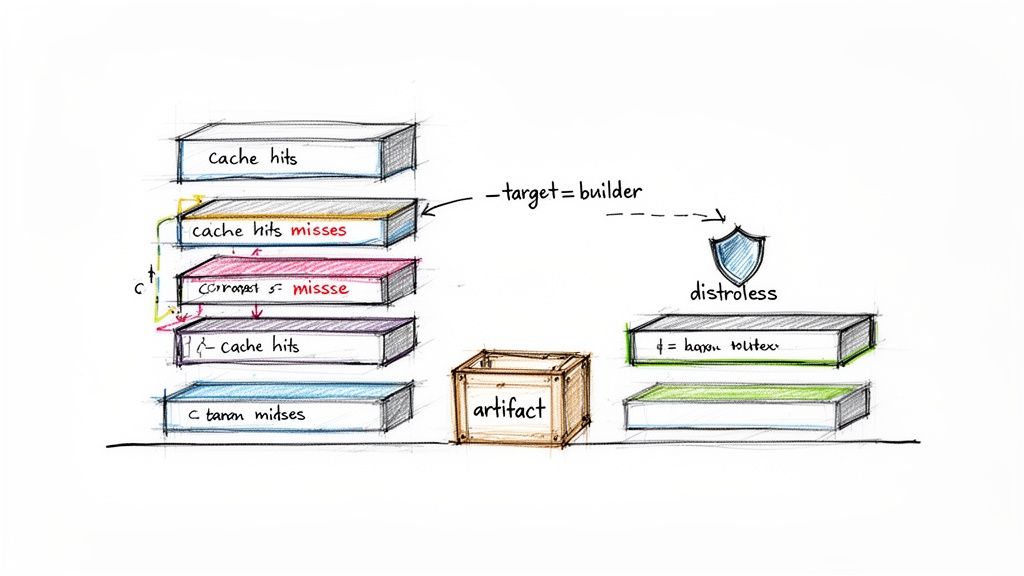

Harden and Minimize Base Images: Start with the smallest possible base image (e.g., Alpine or "distroless" images from Google). A smaller attack surface means fewer packages, libraries, and potential vulnerabilities to manage.

- Action: Use multi-stage Docker builds to separate the build environment from the final runtime image. This ensures build tools like compilers and test frameworks are not included in the production container, drastically reducing its size and attack surface.

-

Implement Image Signing and Provenance: Use tools like Sigstore/Cosign or Docker Content Trust to cryptographically sign container images. This allows you to verify the image's origin and ensure it hasn't been tampered with before it's deployed.

- Example: Configure a Kubernetes admission controller like Kyverno or OPA/Gatekeeper to enforce a policy that requires all images deployed into a production namespace to have a valid signature verified against a specific public key.

-

Enforce Runtime Security Best Practices: Run containers as non-root users and use a read-only root filesystem wherever possible. Leverage runtime security tools like Falco or Aqua Security to monitor container behavior for anomalous activity, such as unexpected process execution or network connections.

- Action: In your Kubernetes pod spec, set the

securityContextwithrunAsUser: 1001,readOnlyRootFilesystem: true, andallowPrivilegeEscalation: falseto apply these hardening principles at deployment time.

- Action: In your Kubernetes pod spec, set the

10. Application Security and Secure Development Practices

Securing the cloud infrastructure is only half the battle; the applications running on it are often the primary target. Integrating security into the software development lifecycle (SDLC), a practice known as "shifting left" or DevSecOps, is essential for building resilient and secure cloud-native applications. This involves embedding security checks, scans, and best practices directly into the development workflow, from coding to deployment.

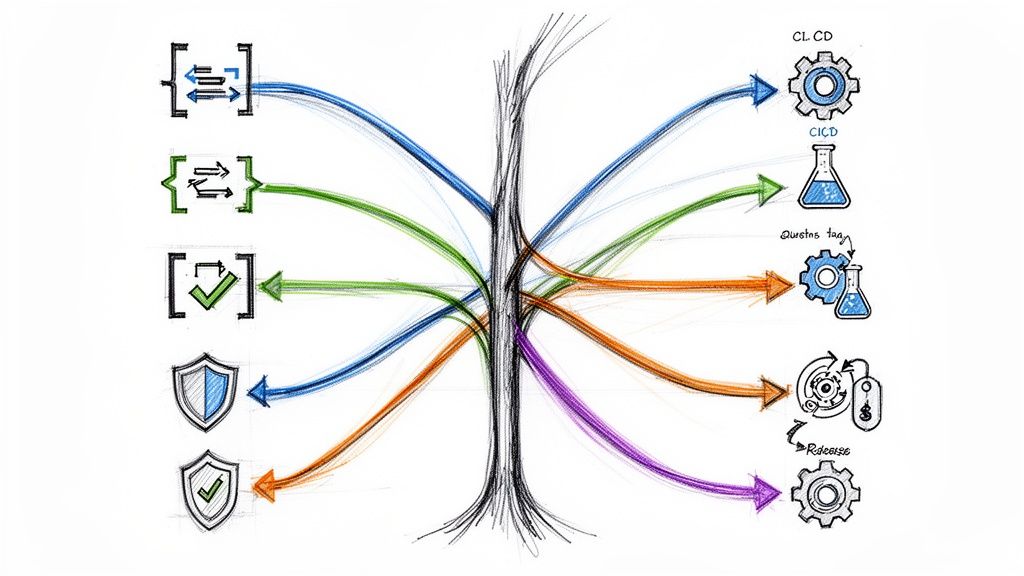

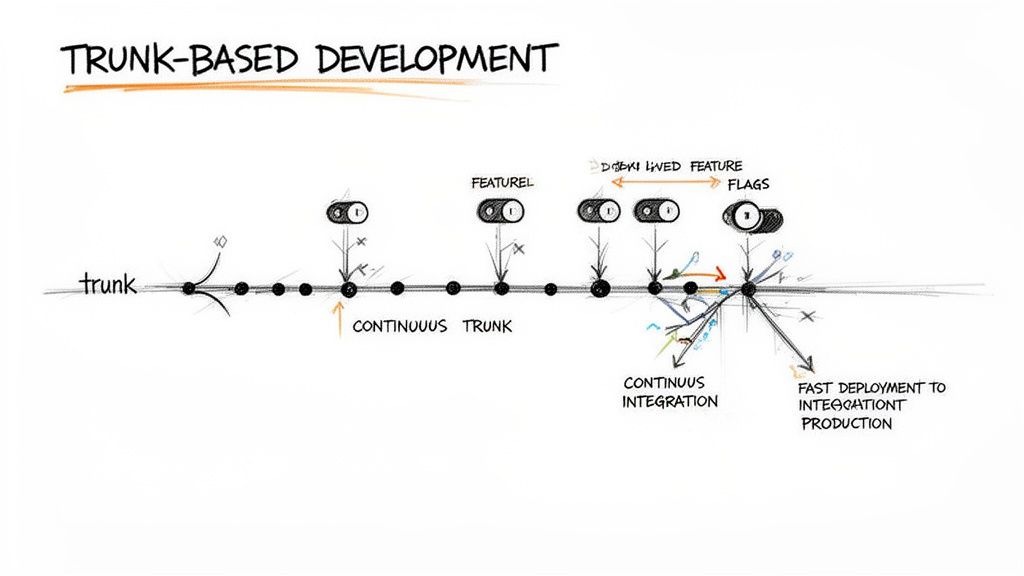

The core goal is to identify and remediate vulnerabilities early when they are significantly cheaper and easier to fix. By making security a shared responsibility of the development team, you reduce the risk of deploying code with critical flaws like SQL injection, cross-site scripting (XSS), or insecure dependencies. This proactive approach treats security not as a final gate but as an integral aspect of software quality throughout the entire CI/CD pipeline.

Why It's Foundational

Applications are the gateways to your data. A vulnerability in your code can bypass even the most robust network firewalls and IAM policies. Without a secure SDLC, your organization continuously accumulates "security debt," making the application more fragile and expensive to maintain over time. A strong application security program is a critical component of any comprehensive cloud security checklist, as it directly hardens the most dynamic and complex layer of your tech stack.

Implementation Examples and Actionable Tips

To effectively integrate security into development, teams must automate testing within the CI/CD pipeline and empower developers with the right tools and knowledge.

-

Integrate SAST and DAST into CI/CD Pipelines: Automate code analysis to catch vulnerabilities before they reach production. Static Application Security Testing (SAST) tools scan source code, while Dynamic Application Security Testing (DAST) tools test the running application. To learn more about integrating these practices, you can explore this detailed guide on implementing a DevSecOps CI/CD pipeline.

- Example: Configure a GitHub Action that runs a Semgrep or Snyk Code scan on every pull request, blocking merges if high-severity vulnerabilities are detected. For DAST, add a job that runs an OWASP ZAP baseline scan against the application deployed in a staging environment.

-

Automate Dependency and Secret Scanning: Open-source libraries are a major source of risk. Use tools to continuously scan for known vulnerabilities (CVEs) in your project's dependencies and scan repositories for hardcoded secrets like API keys or passwords.

- Action: Use Dependabot or Renovate to automatically create pull requests to upgrade vulnerable packages. This reduces the manual effort of dependency management and keeps libraries up-to-date with security patches.

-

Conduct Regular Threat Modeling: For new features or significant architectural changes, conduct threat modeling sessions. This structured process helps teams identify potential security threats, vulnerabilities, and required mitigations from an attacker's perspective.

- Example: Use the STRIDE model (Spoofing, Tampering, Repudiation, Information Disclosure, Denial of Service, Elevation of Privilege) to analyze data flows for a new microservice handling user payment information. Document outputs using a tool like OWASP Threat Dragon.

-

Establish and Enforce Secure Coding Standards: Provide developers with clear guidelines based on standards like the OWASP Top 10. Document best practices for input validation, output encoding, authentication, and error handling.

- Action: Use linters and code quality tools like SonarQube to automatically enforce coding standards and identify security hotspots. Integrate these checks into the CI pipeline to provide immediate feedback to developers on pull requests.

Cloud Security Checklist: 10-Point Comparison

| Control | Implementation complexity | Resource requirements | Expected outcomes | Ideal use cases | Key advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identity and Access Management (IAM) Configuration | High initial complexity; ongoing governance required | IAM policy design, IaC, MFA, audit logging, role lifecycle management | Least-privilege access, reduced unauthorized access, audit trails | Multi-account clouds, remote DevOps, CI/CD integrations | Minimizes breach risk, scalable permission control, compliance-ready |

| Network Security and Segmentation | High design complexity; careful architecture needed | Network architects, VPCs/subnets, firewalls, flow logs, service mesh | Segmented zones, limited lateral movement, improved traffic visibility | Multi-tier applications, regulated data, containerized microservices | Limits blast radius, enables microsegmentation, supports compliance |

| Encryption in Transit and at Rest | Moderate–high (key management is critical) | KMS/HSM, key rotation, TLS certs, encryption tooling | Data confidentiality, compliance with standards, secure backups | Sensitive data, cross-region storage, regulated environments | Protects data if storage compromised; strong compliance support |

| Cloud Infrastructure Compliance & Configuration Management | Moderate–high (IaC and policy integration) | IaC (Terraform/CF), policy-as-code, scanners, remote state management | Consistent deployments, drift detection, automated compliance checks | Large infra, multi-team orgs, audit-heavy environments | Reproducible infrastructure, automated governance, fewer misconfigs |

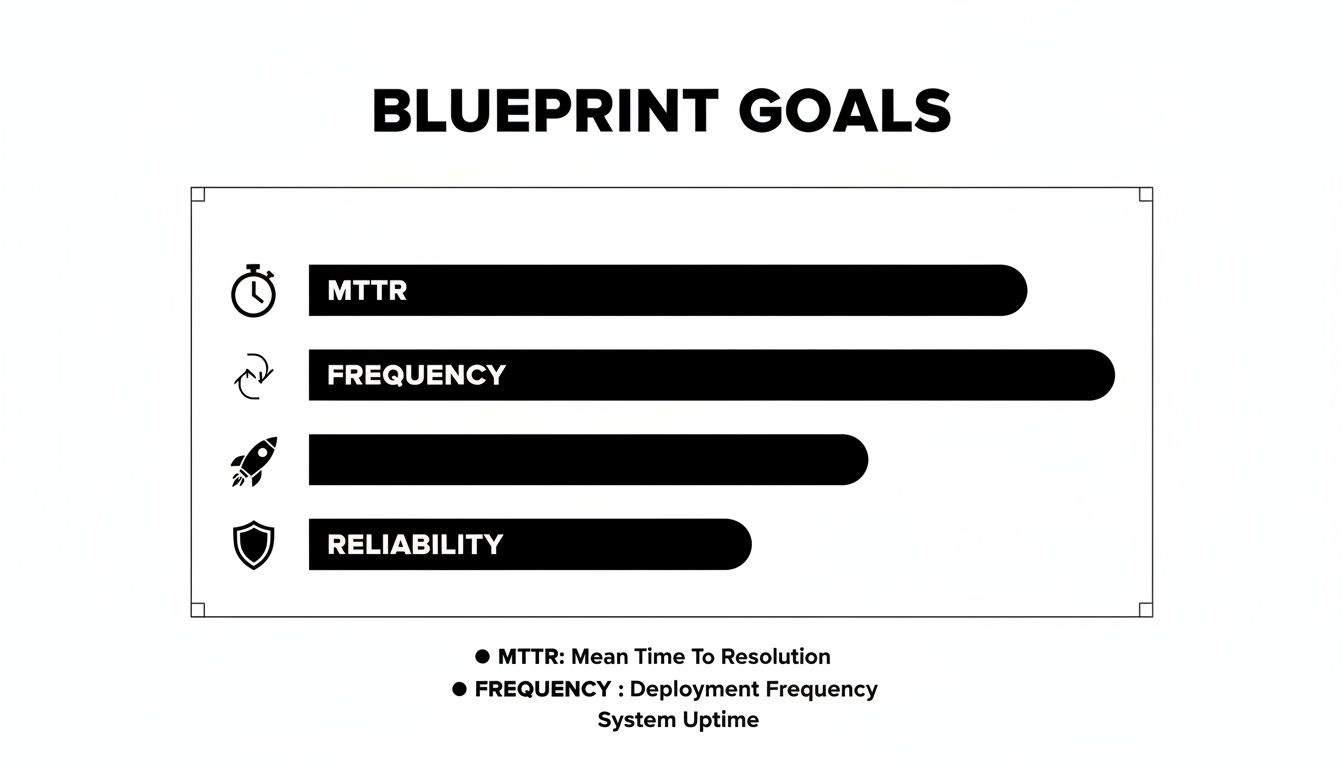

| Logging, Monitoring, and Alerting | Moderate (integration and tuning effort) | Centralized logging, SIEM/metrics, dashboards, retention storage | Faster detection and response, forensic evidence, performance insights | Production systems, SRE, incident response teams | Improves MTTD/MTTR, audit trails, operational visibility |

| Data Backup and Disaster Recovery | Moderate (planning and testing required) | Backup storage, cross-region replication, runbooks, recovery tests | Business continuity, recoverable data, defined RTO/RPO | Critical business systems, ransomware protection, DR planning | Ensures rapid recovery, regulatory retention, operational resilience |

| Vulnerability Management and Patch Management | Moderate (continuous process integration) | Scanners, SCA/SAST tools, patch pipelines, staging/testing | Fewer exploitable vulnerabilities, prioritized remediation | CI/CD pipelines, dependency-heavy projects, container workloads | Proactive risk reduction, shift-left detection, supply-chain visibility |

| Secrets Management and Rotation | Moderate (integration and availability concerns) | Secret vaults (Vault/Secrets Manager), rotation automation, access controls | No hardcoded creds, auditable secret access, rapid rotation | CI/CD, distributed apps, multi-environment deployments | Reduces credential compromise, simplifies rotation, strong auditability |

| Container and Container Registry Security | Moderate–high (lifecycle and runtime controls) | Image scanners, private registries, signing tools, runtime monitors | Trusted images, blocked malicious images, runtime threat detection | Kubernetes/microservices, container-first deployments | Shift-left image scanning, provenance verification, runtime protection |

| Application Security and Secure Development Practices | Moderate (tooling + cultural change) | SAST/DAST/SCA, developer training, CI integration, code reviews | Fewer code vulnerabilities, secure SDLC, developer security awareness | Active development teams, security-sensitive apps, regulated sectors | Early vulnerability detection, lower remediation cost, improved code quality |

Turning Your Checklist into a Continuous Security Program

Navigating the complexities of cloud security can feel like a monumental task, but the detailed checklist provided in this article serves as your technical roadmap. We've journeyed through ten critical domains, from the foundational principles of Identity and Access Management (IAM) and Network Security to the dynamic challenges of Container Security and Secure Development Practices. Each item on this list represents not just a control to implement, but a strategic capability to cultivate within your engineering culture.

The core takeaway is this: a cloud security checklist is not a one-time setup. It is the blueprint for a living, breathing security program that must be woven into the fabric of your daily operations. The true power of this framework is realized when it transitions from a static document into a dynamic, automated, and continuous process. Your cloud environment is in constant flux, with new services being deployed, code being updated, and configurations being altered. A static security posture will inevitably decay, leaving gaps for threats to exploit.

From Static Checks to Dynamic Assurance

The most effective security programs embed the principles of this checklist directly into their DevOps lifecycle. This strategic shift transforms security from a reactive, gate-keeping function into a proactive, enabling one. Instead of performing manual audits, you build automated assurance.

Consider these key transformations:

- IAM Audits become IAM-as-Code: Instead of manually reviewing permissions every quarter, you define IAM roles and policies in Terraform or CloudFormation. Any proposed change is subject to a pull request, peer review, and automated linting against your security policies before it ever reaches production. This codifies the principle of least privilege.

- Vulnerability Scans become Integrated Tooling: Instead of running ad-hoc scans, you integrate static application security testing (SAST) and dynamic application security testing (DAST) tools directly into your CI/CD pipeline. A build fails automatically if it introduces a high-severity vulnerability, preventing insecure code from being deployed.

- Compliance Checks become Continuous Monitoring: Instead of preparing for an annual audit, you deploy cloud security posture management (CSPM) tools that continuously scan your environment against compliance frameworks like SOC 2 or HIPAA. Alerts are triggered in real-time for any configuration drift, allowing for immediate remediation.

This "shift-left" philosophy, where security is integrated earlier in the development process, is no longer a niche concept; it's an operational necessity. By automating the verification steps outlined in our cloud security checklist, you create a resilient feedback loop. This not only strengthens your security posture but also accelerates your development velocity by catching issues when they are cheapest and easiest to fix.

Your Path Forward: Prioritize, Automate, and Evolve

As you move forward, the goal is to operationalize this knowledge. Begin by assessing your current state against each checklist item and prioritizing the most significant gaps. Focus on high-impact areas first, such as enforcing multi-factor authentication across all user accounts, encrypting sensitive data stores, and establishing comprehensive logging and monitoring.

Once you have a baseline, the next imperative is automation. Leverage Infrastructure as Code (IaC) to create repeatable, secure-by-default templates for your resources. Implement policy-as-code using tools like Open Policy Agent (OPA) to enforce guardrails within your CI/CD pipelines and Kubernetes clusters. This programmatic approach is the only way to maintain a consistent and scalable security posture across a growing cloud footprint.

Ultimately, mastering the concepts in this cloud security checklist provides a profound competitive advantage. It builds trust with your customers, protects your brand reputation, and empowers your engineering teams to innovate safely and rapidly. A robust security program is not a cost center; it is a foundational pillar that supports sustainable growth and long-term resilience in the digital age. Treat this checklist as your starting point, and commit to the ongoing journey of refinement and adaptation.

Ready to transform this checklist from a document into a fully automated, resilient security program? The elite freelance DevOps and SRE experts at OpsMoon specialize in implementing these controls at scale using best-in-class automation and Infrastructure as Code. Build your secure cloud foundation with an expert from OpsMoon today.