Feature flagging software is a system that allows teams to modify application behavior without changing code. It functions by wrapping new functionality within conditional logic (e.g., an if/else block) whose state is controlled remotely. This decouples code deployment from feature release, enabling advanced software delivery patterns like canary releases, dark launching, and A/B testing.

What Is Feature Flagging Software and Why Does It Matter

At its core, feature flagging breaks the monolithic link between deployment (the act of pushing compiled code to a production environment) and release (the act of making functionality available to users). In traditional software delivery, these events are atomic. When new code is deployed to a server, it is immediately live for all users. This creates high-stakes, "big bang" release events where a single bug can trigger a full-system rollback.

Feature flags, or toggles, provide a control plane to manage this risk. A developer wraps any new code block in a conditional statement controlled by a flag. This allows them to merge and deploy potentially incomplete or untested code into the main branch, with the feature safely deactivated behind a flag that evaluates to false. The code exists in the production environment but remains dormant and inert, generating no user-facing impact.

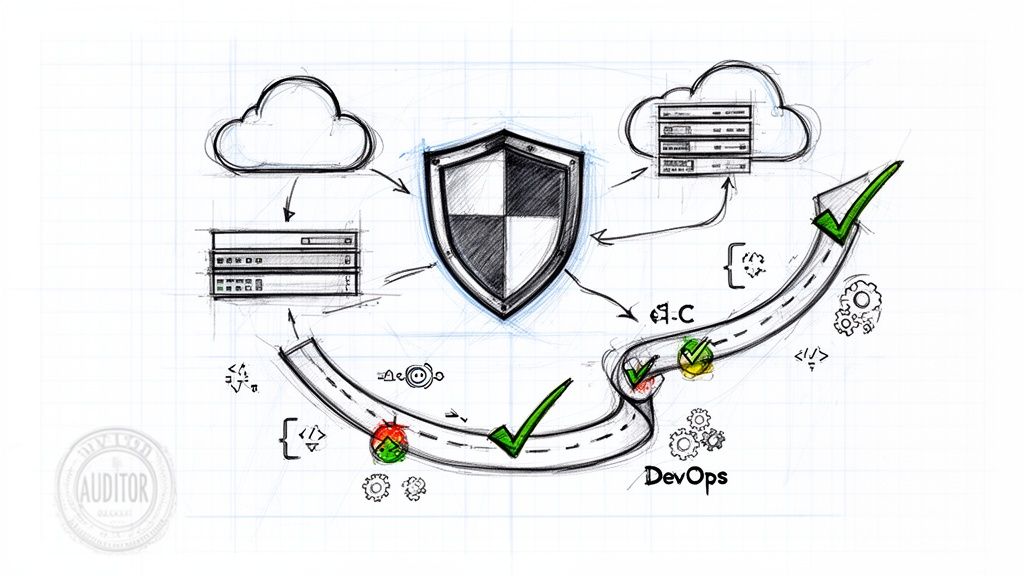

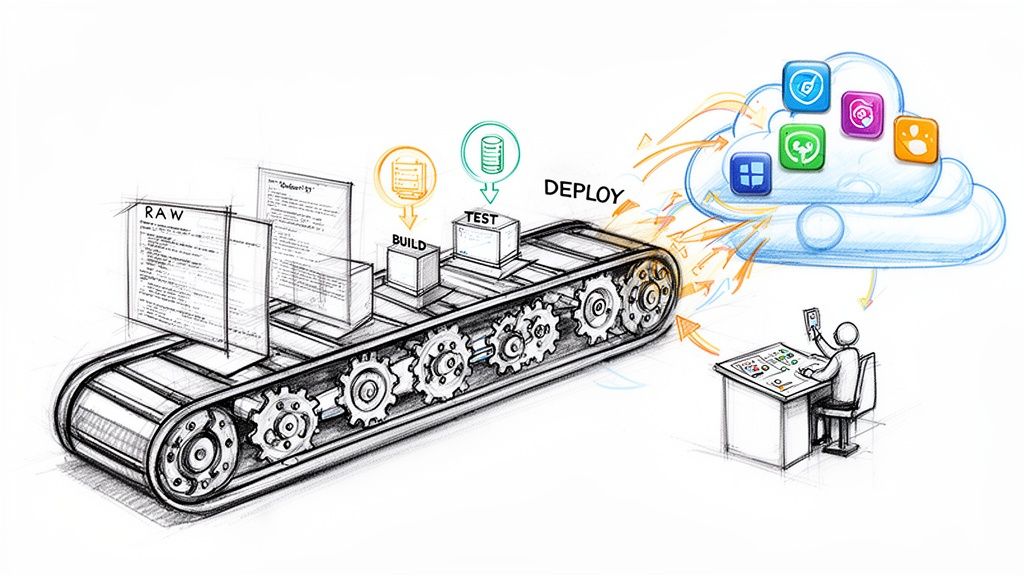

Decoupling Deployment from Release

This decoupling is a foundational principle of modern DevOps and Continuous Delivery. It enables teams to merge small, incremental changes to the main branch and deploy them to production multiple times per day. The release of a feature transitions from a high-risk technical event to a controlled business decision.

A feature flag is a remote-control mechanism that changes system behavior without a new code deployment, transforming high-risk, all-or-nothing release cycles into low-risk, incremental rollouts.

When a feature is deemed ready, a product manager or engineer can modify the flag's state via a central management UI or API. The feature is instantly activated for a targeted user segment. If an issue is detected, the flag is toggled off, immediately mitigating the impact. This "kill switch" functionality eliminates the need for emergency hotfixes or complex rollback procedures.

The adoption of this practice is reflected in market growth. The global feature management software market, valued at $304 million in 2024, is projected to reach $521 million by 2032, driven by the need for safer, more agile development cycles. You can explore the data driving this trend in the feature management market projections from Intel Market Research.

The Technical Advantages of Using Flags

Beyond risk mitigation, feature flagging enables powerful, data-driven software delivery strategies. These digital switches provide the architectural foundation for a more controlled and experimental approach to product development.

The table below outlines the direct technical and business impacts of adopting a feature flagging system.

| Core Benefits of Feature Flagging Software |

| :— | :— | :— |

| Benefit | Technical Impact | Business Outcome |

| Risk Reduction | Decouples deployment from release, enabling kill switches and canary releases. | Minimizes downtime and protects revenue by containing bugs instantly. |

| Increased Velocity | Allows developers to merge and deploy code continuously without waiting for full feature completion. | Accelerates time-to-market and allows the business to respond faster to market changes. |

| Targeted Rollouts | Enables control over who sees a feature based on user attributes (e.g., location, subscription plan). | Facilitates premium feature tiers, regional launches, and internal beta testing. |

| Experimentation | Powers A/B/n testing by serving different feature variations to distinct user segments. | Drives data-informed product decisions, improving user engagement and conversion rates. |

| Operational Control | Provides an emergency "off switch" to disable faulty or resource-intensive features instantly. | Enhances system stability and reduces the mean time to recovery (MTTR) during incidents. |

By integrating these capabilities into your software development lifecycle (SDLC), you adopt a more resilient and data-centric methodology.

Here are the most common techniques enabled by feature flags:

- Canary Releases: Instead of a 100% "big bang" launch, a new feature is exposed to a small percentage of the user base (e.g., 1%, then 5%, then 20%). During this phased rollout, performance metrics are monitored to ensure stability, dramatically reducing the "blast radius" of potential bugs.

- Dark Launching: Backend services or infrastructure changes are deployed and tested with real production traffic without being visible to any users. This is ideal for validating the performance and stability of a database migration or a new microservice API before the official launch.

- A/B Testing: Multiple variations of a feature are served to different user segments simultaneously to measure their impact on key business metrics. This provides quantitative data to validate which implementation best achieves a specific goal.

- Kill Switches: An operational toggle that provides an immediate "off switch" for a feature. If a new feature causes performance degradation or critical errors, it can be disabled instantly for all users with a single click, providing the fastest possible path to incident mitigation.

When integrated into a CI/CD pipeline, feature flagging software transforms releases from a source of high risk and anxiety into a strategic competitive advantage, fostering a culture of safe experimentation and built-in resilience.

Strategic Use Cases for Feature Flagging

Once the fundamental concept of remote control is established, feature flags evolve from a simple safety mechanism into a powerful tool for strategic product development and operational control. These use cases demonstrate how a simple on/off switch can drive business outcomes.

Let's dissect four powerful techniques for leveraging flags in a modern engineering organization.

Canary Releases

A canary release is a technique for rolling out changes to a small subset of users before making them available to everyone. It is a risk-reduction strategy that minimizes the "blast radius" of potential issues by limiting exposure. This allows teams to test new code in the production environment with real traffic while minimizing the impact of any unforeseen bugs or performance bottlenecks.

With a robust feature flagging tool, canary cohorts can be defined with granular precision. For example, a flag for a redesigned dashboard could be activated for:

- 1% of total user traffic, randomly selected.

- Only users with an iOS device and an app version greater than

3.14. - Users with an IP address geolocated to Canada.

During the canary release, engineering teams monitor key performance indicators (KPIs) like error rates, application latency (p95, p99), and CPU utilization. If a negative trend is detected, the flag's "kill switch" is activated, instantly rolling back the feature for the canary group without requiring a code rollback or redeployment.

Dark Launching

Dark launching is the practice of deploying new backend functionality to a production environment but keeping it hidden from end-users. The code executes "in the dark," allowing teams to test non-UI components like refactored microservices, new API endpoints, or database schema changes under real-world conditions.

Consider an e-commerce platform migrating to a new payment processor. A dark launch would allow the team to shadow real payment requests, sending them to the new service in parallel with the old one. The results from the new processor are logged and compared but not acted upon, meaning customers are not charged twice. This provides high-fidelity performance and correctness data without any user impact, building massive confidence before the official cutover.

Dark launching is the ultimate dress rehearsal for your infrastructure. It lets you test critical backend systems with real production traffic, identifying and fixing performance bottlenecks before a single user is affected.

This technique de-risks major architectural changes, providing empirical data to ensure a smooth, uneventful transition when the feature is eventually made live for all users.

A/B Testing and Experimentation

Feature flags are the core engine that enables effective A/B testing and multivariate experimentation. This is the process of comparing two or more versions of a feature to determine which one performs better against a specific business goal. You serve 'Variation A' (the control) to one user segment and 'Variation B' (the challenger) to another, then collect and analyze the resulting data.

A classic example is testing a new call-to-action button. A feature flag can be configured to execute a simple experiment:

- 50% of new users are served the original blue "Sign Up" button (control).

- The other 50% of new users are served a new green "Get Started" button (variation).

By integrating the feature flagging platform with analytics tools, you can directly correlate button visibility with conversion rates. This data-driven approach replaces subjective decision-making with quantitative evidence, allowing you to iterate on the product based on actual user behavior. For more on structuring these experiments, consult these A/B testing best practices.

Entitlement Management

Feature flags provide a clean, scalable mechanism for entitlement management (also known as permissioning). This involves using flags to control feature access based on user attributes like subscription tier, role, or other entitlements. It decouples feature access from the core application logic, avoiding complex, hard-coded permission checks scattered throughout the codebase.

A SaaS company can use flags to manage feature access across different customer tiers:

- Free Tier: Users get access to basic reporting.

- Pro Tier: The

advanced-analyticsflag evaluates totrue. - Enterprise Tier: Flags for both

advanced-analyticsandsso-integrationevaluate totrue.

When a customer upgrades their plan, an API call updates their attributes in the feature flagging system, and the newly entitled features become available instantly. No code change or redeployment is required, providing a highly scalable and maintainable way to manage product packaging and upsell paths.

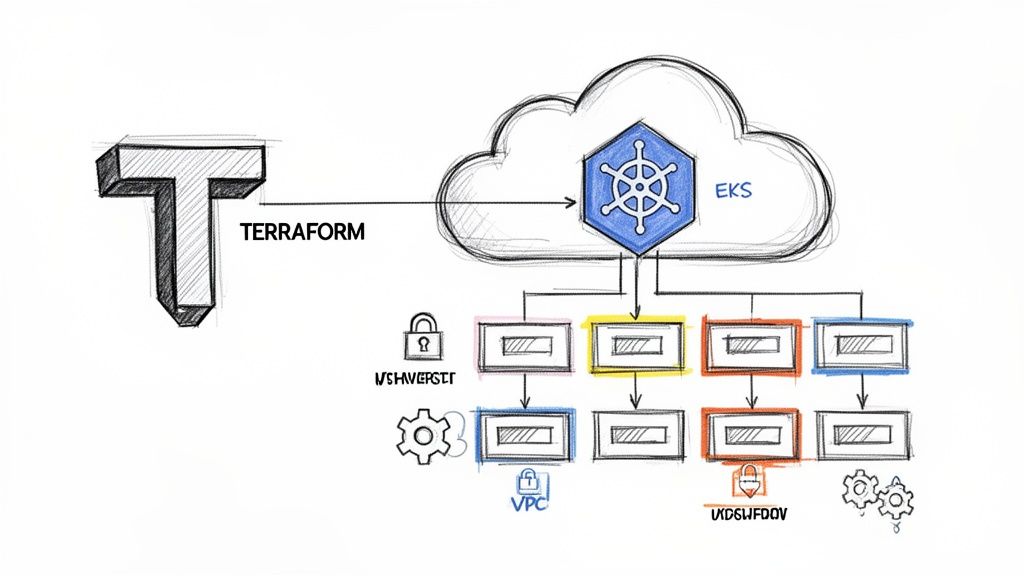

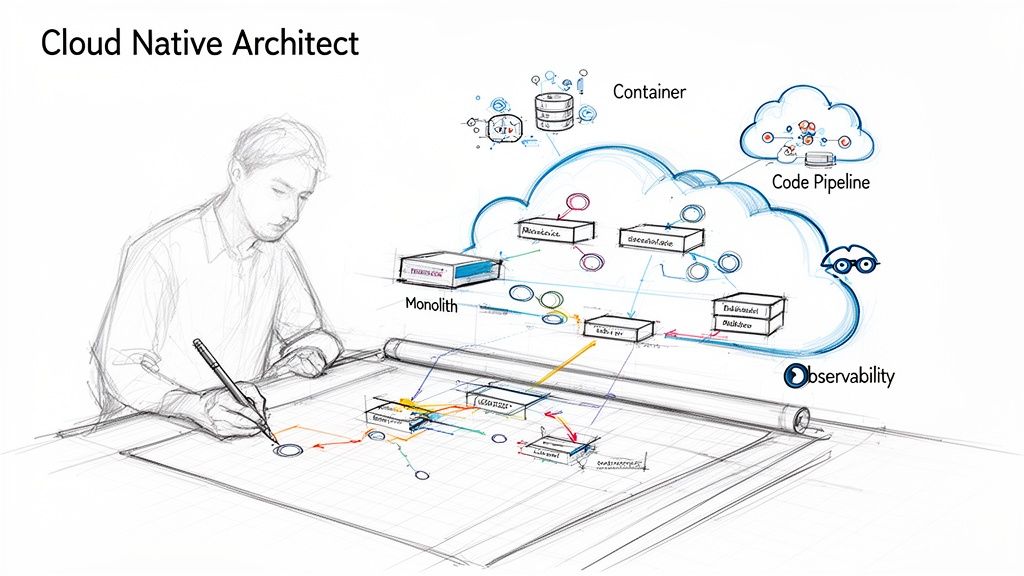

Technical Architecture and CI/CD Integration

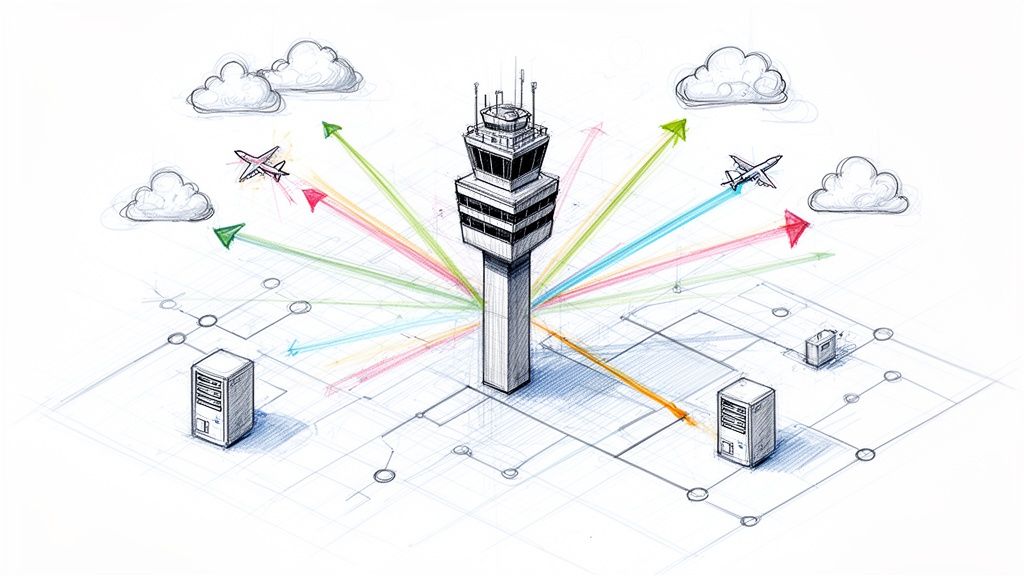

To understand the mechanics of a feature flagging system, it's essential to examine its architecture. A modern feature management platform is a distributed system comprising three core components, engineered for high performance, scalability, and seamless integration into a CI/CD workflow.

The system is orchestrated from a central management console. This web-based UI serves as the single source of truth for all feature flags. Here, teams create and configure flags, define targeting rules (e.g., "activate new-dashboard for 50% of users in Germany"), and review audit logs to track changes.

The console communicates flag rules to the Software Development Kits (SDKs) embedded in the application code. These SDKs come in two primary types:

- Server-Side SDKs: Integrated into backend services (e.g., Node.js, Go, Java), these are ideal for controlling backend logic, API responses, or infrastructure-level changes.

- Client-Side SDKs: Embedded in frontend applications (e.g., React, Vue, iOS, Android), these manage UI elements and user-facing interactions.

The critical architectural detail is performance. SDKs do not issue a network request to the central service for every flag evaluation. Instead, they fetch the full set of rules upon application startup and cache them in-memory. This makes flag evaluation an extremely fast local function call that adds virtually zero latency to application requests.

Integrating Flags into Your CI/CD Pipeline

The true power of feature flagging software is realized when it is integrated into a Continuous Integration/Continuous Deployment (CI/CD) pipeline. Using tools like Jenkins, GitLab CI, or GitHub Actions, flag management becomes an automated step in the software delivery process, rather than a manual post-deployment action.

This enables automated progressive delivery. For instance, a CI/CD pipeline can be configured to automatically execute a job after a successful production deployment that uses the feature flagging platform's API to activate a new feature for 1% of traffic.

The diagram below illustrates how this architecture enables core delivery strategies that can be automated within a pipeline.

Strategies like canary releases and dark launches are powered by this architecture and automated via the DevOps toolchain. For a detailed implementation guide, see our article on how to implement feature toggles.

The rise of feature flagging in the mid-2010s coincided with the mainstream adoption of DevOps, as tech leaders used toggles to achieve progressive delivery at scale. Teams that implement these practices often report 85% reductions in their mean time to recovery (MTTR)—a critical KPI for any team managing a CI/CD pipeline.

Connecting Flags with Observability Platforms

The final architectural component is creating a closed-loop system by integrating the feature flagging platform with observability tools like Datadog, Prometheus, or Dynatrace. This transforms feature flags from a simple deployment mechanism into an intelligent, automated control plane for application health.

By sending events from the feature flag platform (e.g., "flag new-checkout-flow now at 20% rollout") to monitoring systems, teams can directly correlate feature rollouts with performance metrics. This allows for real-time visualization of a feature's impact on error rates, latency, or system load.

Consider a scenario where an observability platform detects a spike in 500-series HTTP errors. It automatically correlates this anomaly with a feature flag that was recently enabled. Without human intervention, it triggers a webhook to the feature flagging API, which immediately deactivates the problematic feature. This is the goal of automated, safe delivery.

This closed-loop feedback system represents the pinnacle of release safety. It empowers teams to release code with high velocity, confident that the system can automatically detect and mitigate issues before they impact a significant portion of users, thereby protecting system stability and the on-call team's sanity.

How to Select the Right Feature Flagging Software

Choosing the right feature flagging platform is a critical architectural decision that will have long-term effects on your team's velocity and stability. The ideal solution is not necessarily the one with the most features, but the one that best aligns with your technology stack, performance requirements, and security posture.

This is not a simple tool procurement; it is an investment in your core engineering infrastructure. Here are the critical technical criteria to evaluate.

Can It Keep Up With Your Scale and Performance?

The primary technical consideration is performance. A feature flag evaluation must be executed in microseconds. Any latency introduced at this stage, even a few milliseconds, will be magnified across all requests and can degrade overall application performance significantly.

Your chosen feature flagging software must be architected to handle your peak traffic load without performance degradation. For many applications, this means handling millions or even tens of millions of flag evaluations per second. The key architectural pattern to look for is an in-memory caching model within the SDKs. This ensures that after an initial fetch of flag rules, all subsequent evaluations are performed locally without any network latency.

A feature flag that adds latency is an anti-pattern. The whole point of a high-performance SDK is to make decisions locally and instantly, ensuring your application’s response time is completely unaffected.

How Good is The SDK Support?

A feature flagging platform is only as useful as its SDKs. The vendor must provide high-quality, first-party SDKs for every language, framework, and platform in your technology stack. If your architecture includes a Go backend, a React frontend, and native mobile apps on Swift and Kotlin, you need official, well-maintained SDKs for all of them.

When evaluating SDKs, look for:

- Language Coverage: Does the vendor provide official, first-party SDKs for all your core technologies? Relying on third-party or community-maintained SDKs introduces unacceptable risk.

- Feature Parity: Do all SDKs support the same core capabilities, such as real-time updates (via streaming) and complex attribute-based targeting? Inconsistent behavior across your stack creates implementation complexity.

- Documentation and Maintenance: Is the documentation clear, comprehensive, and up-to-date? Investigate the SDK's GitHub repository. Assess its update frequency, issue response times, and overall maintenance quality.

Is It Secure and Compliant?

Integrating a third-party system that controls your application's logic fundamentally alters your security surface area. A robust security and compliance posture is non-negotiable. Scrutinize the platform's access control mechanisms, data privacy policies, and audit logging capabilities.

Start with role-based access control (RBAC). You need granular permissions to define who can create, modify, or toggle flags within specific environments. For example, a product manager should only have permission to toggle flags in production, whereas a developer needs full control in a staging environment.

The audit trail is equally critical. The system must provide an immutable, timestamped log of every change: who modified a flag, what the change was, and when it occurred. This is a mandatory requirement for compliance standards like SOC 2 and is invaluable for incident forensics.

How Powerful Are the Rollout and Targeting Controls?

The strategic value of feature flagging software lies in its ability to precisely control feature exposure. While simple on/off toggles are useful, advanced capabilities come from sophisticated targeting and rollout controls. Your chosen platform must support attribute-based targeting, allowing you to define dynamic user segments based on contextual data.

For example, can you easily construct targeting rules such as:

planequalspremiumemailends with@yourcompany.comfor internal dogfoodingbeta_testeristrue

Beyond targeting, evaluate the platform's release automation capabilities. Does it support scheduled releases? Can you configure a progressive rollout that automatically increases a feature's exposure percentage over a predefined time window? These are the features that enable safe, automated canary releases.

To structure your evaluation, use the following criteria matrix.

Evaluation Criteria for Feature Flagging Tools

Use this table to compare potential feature flagging solutions against critical technical and business requirements for your organization.

| Criteria | What to Look For | Why It Matters for Your Team |

|---|---|---|

| Scalability & Performance | Local SDK evaluations, low latency (microseconds), high-throughput capacity, global CDN. | Prevents application slowdowns and ensures reliability during peak traffic. |

| SDK Support & Quality | First-party SDKs for all your languages, feature parity, active maintenance, clear docs. | Ensures you can use flags consistently across your entire tech stack without compatibility issues. |

| Security & Compliance | Granular RBAC, SSO integration, immutable audit logs, SOC 2/ISO certifications. | Protects your application from unauthorized changes and helps you meet compliance requirements. |

| Rollout & Targeting | Attribute-based targeting, percentage rollouts, scheduled releases, kill switches. | Gives you precise control to de-risk releases, run A/B tests, and target specific user segments. |

| Auditability & Debugging | Detailed change history (who, what, when), integration with observability tools. | Makes it easy to trace issues back to a specific flag change, drastically reducing incident response time. |

This framework provides a structured approach to selecting a platform. For additional context on how these tools fit into the broader engineering landscape, our DevOps tools comparison guide can be a valuable resource.

Implementation Best Practices and Pitfalls to Avoid

The choice of feature flagging tool is only the first step. The long-term success of the practice depends entirely on establishing a disciplined process. Without strict governance, a feature flagging system can devolve into a source of significant technical debt, increasing complexity and release risk.

To build a sustainable practice, you must codify clear rules from day one.

First, establish a strict naming convention. A flag named test_1 is useless. A descriptive name like feat-checkout-v2-new-payment-gateway-2024-q3 provides immediate context, communicating the feature, its version, its purpose, and its expected retirement date.

This discipline leads directly to the most critical practice: flag lifecycle management. Every flag must be associated with a ticket for its own removal. Without this, your codebase will accumulate stale flags, creating "flag debt" that complicates debugging, increases cognitive load, and introduces unpredictable behavior.

Building a Sustainable Flagging Process

A formal lifecycle process ensures that flags remain temporary instruments, not permanent architectural fixtures. This process must be integrated into your team's standard workflow, alongside code reviews and ticket tracking.

A simple, four-stage lifecycle is a good starting point:

- Creation: Define the flag's name, owner, and purpose. Critically, create a ticket in your issue tracker (e.g., Jira) for its eventual removal.

- Activation: The flag is used in production for a rollout, A/B test, or as an operational kill switch.

- Deactivation: The feature is either fully rolled out (flag is permanently

truefor all users) or abandoned (permanentlyfalse). - Retirement: The developer assigned the removal ticket refactors the code, deleting the conditional logic (

if/elseblock) and archiving the flag in your feature flagging software.

Another essential practice is to define the blast radius for every feature before rollout. This involves analyzing the potential impact of a failure. Will it affect all users? Only mobile users? Only customers on a specific plan? This analysis informs the progressive delivery strategy and incident response plan. You can learn more about managing feature flags effectively in our dedicated guide.

Common Pitfalls You Must Avoid

While good hygiene sets you up for success, understanding common anti-patterns is equally important. These are the classic mistakes that can turn a powerful tool into a dangerous liability.

The most dangerous pitfall is creating tangled, nested flag dependencies, where the logic of one flag depends on the state of another. This creates a combinatorial explosion of states that is impossible to reason about, test, or debug. A change to one flag can trigger a cascade of unintended consequences.

Avoid nested flags at all costs. Each feature flag should be an independent switch. If you find yourself writing

if (flagA) { if (flagB) { ... } }, it's a giant red flag that you need to rethink your implementation.

Failing to maintain a complete audit trail is another critical error. During an incident, the first question is always, "What changed?" An immutable audit log detailing who toggled which flag and when is the fastest way to find the root cause.

Finally, do not neglect to integrate flag state changes with your monitoring systems. Toggling a feature without observing its impact on performance and error rates is flying blind. Your observability platform must be able to correlate a spike in latency directly back to the feature flag that was just enabled.

How OpsMoon Accelerates Your Feature Flagging Strategy

Adopting a feature flagging strategy is a sound architectural decision, but the implementation path is fraught with technical challenges. OpsMoon acts as a strategic partner, providing the elite engineering talent required to bridge the gap between strategy and successful execution.

We provide a direct path to a world-class feature flagging practice, tailored to your specific technical environment. Our experts guide you through the complex vendor landscape, ensuring the feature flagging software you select meets your unique scale, security, and performance requirements.

From Architecture to Execution

Our engagement extends far beyond tool selection. OpsMoon’s top-tier DevOps engineers—from the top 0.7% of global talent—will architect the full integration. We perform the heavy lifting of integrating your chosen feature management platform into your existing CI/CD pipelines and observability stack.

This expert-led implementation de-risks the adoption process and dramatically shortens your time-to-value. We help you establish the critical best practices discussed in this guide, including:

- Flag Lifecycle Management: Building an automated process for retiring stale flags to control technical debt.

- Automated Progressive Delivery: Integrating flag automation directly into your CI/CD pipeline to enable safe, programmatic canary releases.

- Closed-Loop Observability: Creating a feedback loop between your flagging platform and monitoring tools to correlate feature changes with real-time performance impact.

By partnering with OpsMoon, you get to skip the steep learning curve and avoid the massive overhead of hiring and training a specialized in-house team. We bring the expertise you need, right when you need it, to master progressive delivery and build more resilient software.

Ultimately, working with OpsMoon means you are not just implementing a tool; you are embedding a mature, scalable feature management capability into your engineering DNA. We empower your team to deploy faster and with greater confidence, transforming your release process from a source of risk into a definitive competitive advantage.

Frequently Asked Questions

As teams begin to explore feature flagging, several technical questions consistently arise. Here are practical, in-the-weeds answers to the most common queries.

What Is the Difference Between Feature Flagging and Configuration Management

While conceptually similar, these two systems solve fundamentally different problems.

Configuration management deals with static, environment-specific variables that change infrequently. Examples include database connection strings, API keys for third-party services, and port numbers. These values are typically set at build or deploy time and define the static environment in which the application runs.

Feature flagging software is designed for dynamic, runtime control of application logic. Flags are intended to be changed frequently, often by non-technical users like product managers, to control feature visibility and behavior for different user segments.

While a configuration file could be used for a simple binary toggle, a dedicated feature flagging platform provides a suite of capabilities that config management lacks:

- Percentage-based rollouts for gradual exposure.

- Attribute-based user targeting for canary testing and segmentation.

- Immutable audit logs for compliance and debugging.

- A non-technical UI for business-led release management.

In short: configuration sets the stage; feature flags direct the dynamic action that occurs on it.

Can Feature Flags Create Technical Debt

Yes, unequivocally. Unmanaged feature flags are a significant source of "flag debt." This occurs when flags are left in the codebase long after their associated feature has been fully rolled out or abandoned. Each forgotten flag represents a dead code path and a conditional branch that increases cognitive load, complicates testing, and creates a risk of unpredictable behavior.

Stale flags are not benign. They are dormant logic bombs waiting to cause unpredictable behavior when conditions change unexpectedly. A formal flag lifecycle management process is the only way to defuse them.

This is why a strict lifecycle for every flag is non-negotiable. From its inception, a flag requires a clear naming convention, a designated owner, and a ticket scheduled for its removal. Treat flags as temporary scaffolding, not a permanent part of your application's architecture.

Should I Build or Buy a Feature Flagging System

Building a simple boolean toggle is trivial. Building an enterprise-grade, production-ready feature flagging software platform is a massive, often underestimated engineering endeavor.

A mature system requires far more than a toggle:

- A highly available, low-latency evaluation engine capable of handling millions of evaluations per second.

- High-performance SDKs for every language and framework in your stack (e.g., Go, React, Kotlin, Swift).

- A secure management UI with granular role-based access control (RBAC) and SSO integration.

- An immutable audit trail for security compliance and incident forensics.

- Complex targeting logic to enable sophisticated progressive delivery strategies.

Commercial and mature open-source platforms have invested thousands of engineering hours into solving these hard problems at scale. For the vast majority of organizations, the ROI of buying a dedicated solution is far greater than building one. It allows your engineers to focus on your core product, not on reinventing complex infrastructure.

How Do Feature Flags Impact Application Performance

A well-architected feature flagging system should have a negligible impact on application performance. This is achieved through the design of modern SDKs, which do not make a network call to a central server for every flag evaluation.

Instead, the SDK fetches the entire set of flag rules upon application startup and caches them in memory. All subsequent flag evaluations are local function calls that execute in microseconds, adding no blocking latency to your application's request/response cycle. The SDK then uses a background process (often a streaming connection) to listen for updates and refresh the in-memory cache asynchronously when a rule changes.

However, a poorly implemented homegrown system or a platform that encourages complex, chained rule evaluations can introduce latency. This is precisely why selecting a high-performance, battle-tested platform is a critical upfront architectural decision.

Ready to implement a world-class feature flagging strategy without the risk and overhead? OpsMoon connects you with elite DevOps experts who can architect and integrate the perfect solution for your CI/CD and observability stack, accelerating your journey to safer, faster deployments. Book a free work planning session and get matched with top 0.7% global talent today.