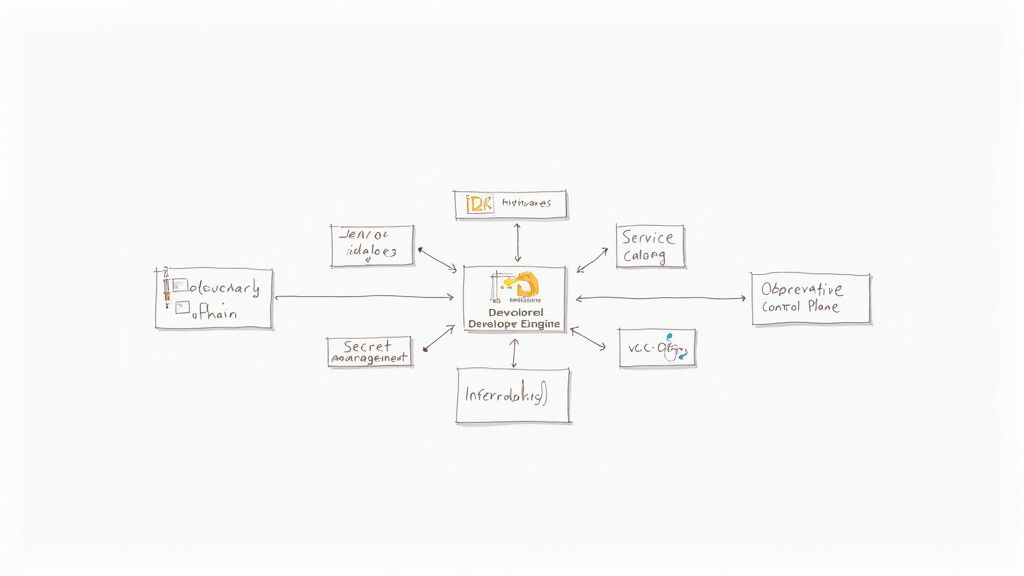

A DevOps consulting company provides specialized engineering teams to architect, implement, and optimize your software delivery lifecycle and cloud infrastructure. They act as strategic partners, applying automation, cloud-native principles, and site reliability engineering (SRE) practices to a single goal: accelerating your software delivery velocity while improving system stability and security. Their core function is to solve complex technical challenges related to infrastructure, CI/CD, and operations.

Why Your Business Needs a DevOps Consulting Company

In a competitive market, internal teams are often constrained by the operational overhead of complex toolchains, mounting technical debt, and inefficient release processes. This friction leads to slower feature delivery, developer burnout, and increased risk of production failures. A specialized DevOps consulting company addresses these technical bottlenecks directly. They don't just recommend tools; they implement and integrate them, driving fundamental improvements to your engineering workflows.

This need for deep technical expertise is reflected in market data. The global DevOps consulting sector is projected to expand from approximately $8.6 billion in 2025 to $16.9 billion by 2033. This growth is driven by the clear technical and business advantages of a mature DevOps practice.

Before evaluating potential partners, it's crucial to understand the specific technical domains where they deliver value. Their services are typically segmented into key areas, each targeting a distinct part of the software development and operational lifecycle.

Core Services Offered by a DevOps Consulting Company

Here is a technical breakdown of the primary service domains. Use this to identify specific gaps in your current engineering capabilities.

| Service Category | Key Activities & Tools | Technical Impact |

|---|---|---|

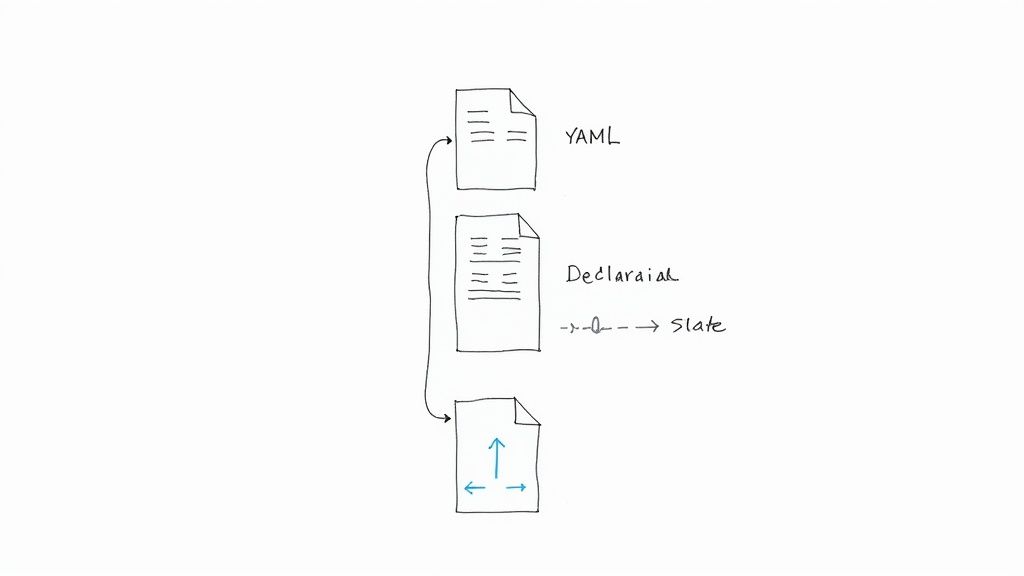

| CI/CD Pipeline & Automation | Architecting multi-stage, YAML-based pipelines in tools like Jenkins (declarative), GitLab CI, or GitHub Actions. Implementing build caching, parallel job execution, and artifact management. | Reduces lead time for changes by automating build, test, and deployment workflows. Enforces quality gates and minimizes human error in release processes. |

| Cloud Infrastructure & IaC | Provisioning and managing immutable infrastructure using declarative tools like Terraform or imperative SDKs like Pulumi. Structuring code with modules for reusability and managing state remotely. | Creates reproducible, version-controlled cloud environments. Enables automated scaling, disaster recovery, and eliminates configuration drift between dev, staging, and prod. |

| DevSecOps & Security | Integrating SAST (e.g., SonarQube), DAST (e.g., OWASP ZAP), and SCA (e.g., Snyk) scanners into CI pipelines as blocking quality gates. Managing secrets with Vault or cloud-native services. | Shifts security left, identifying vulnerabilities in code and dependencies before they reach production. Reduces the attack surface and minimizes the cost of remediation. |

| Observability & Monitoring | Implementing the three pillars of observability: metrics (e.g., Prometheus), logs (e.g., ELK Stack, Loki), and traces (e.g., Jaeger). Building actionable dashboards in Grafana. | Provides deep, real-time insight into system performance and application behavior. Enables rapid root cause analysis and proactive issue detection based on service-level objectives (SLOs). |

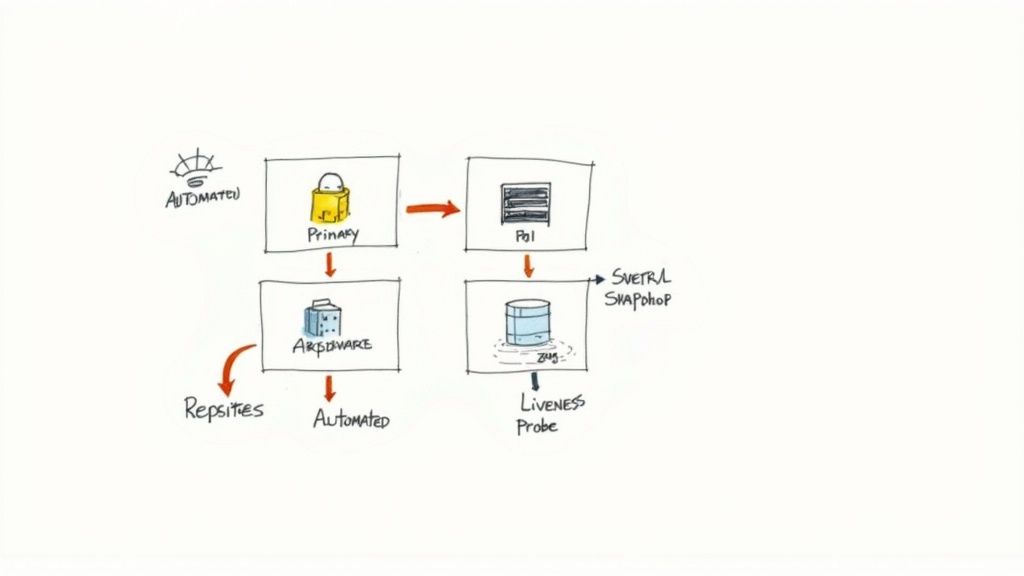

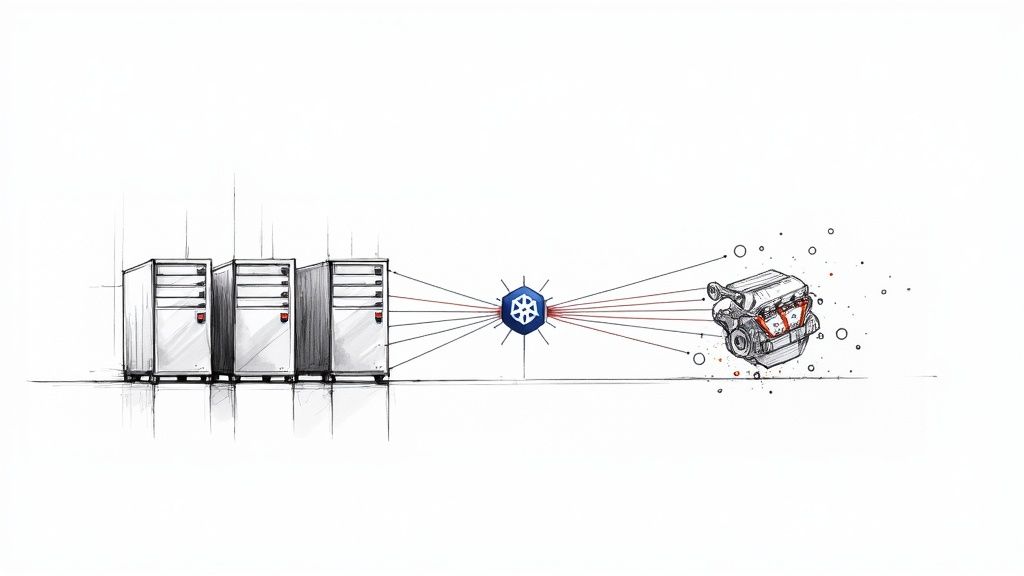

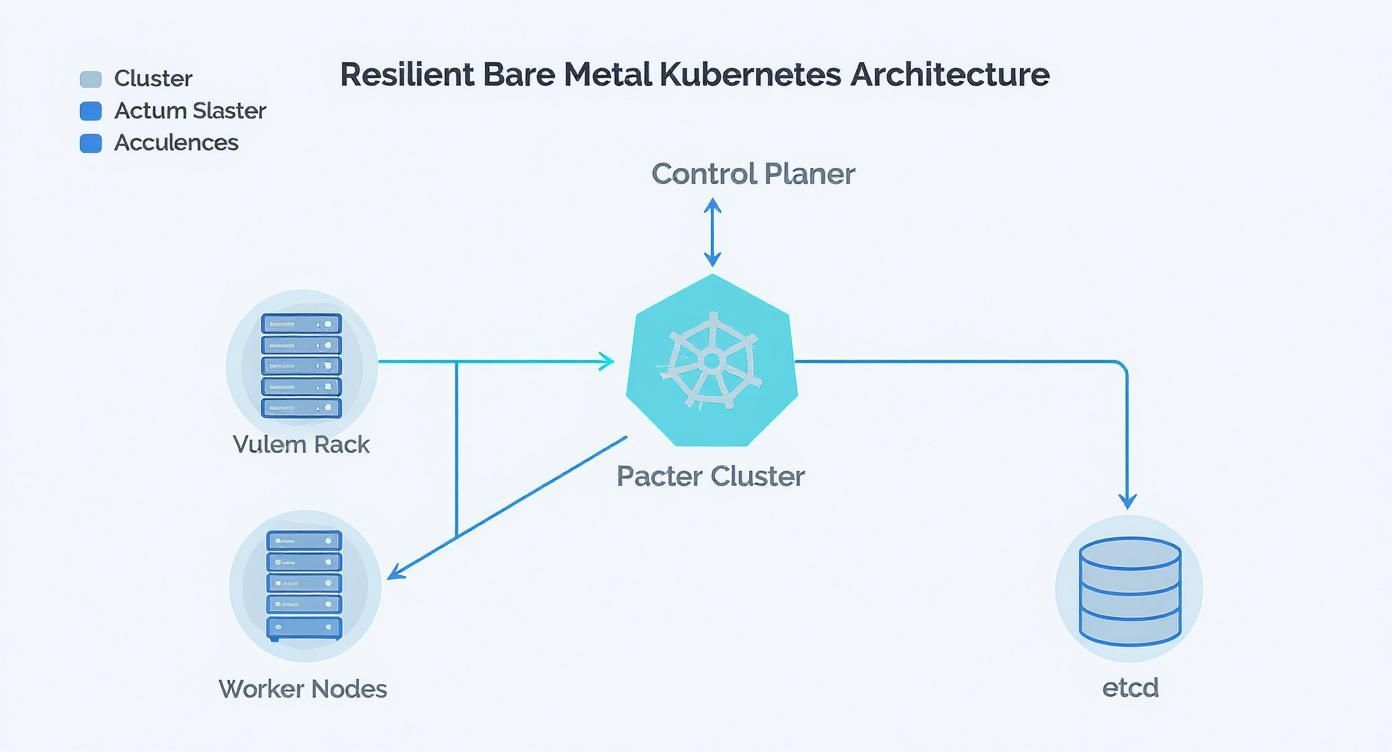

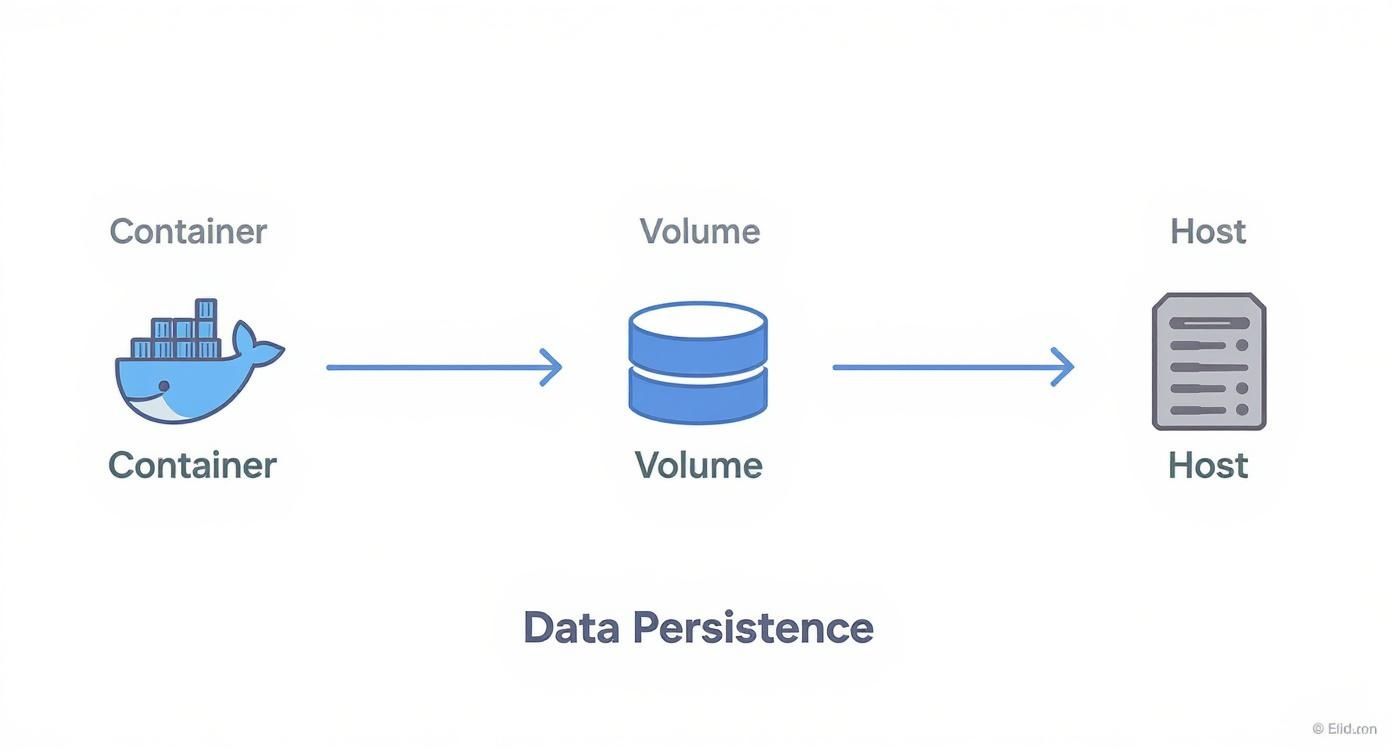

| Kubernetes & Containerization | Designing and managing production-grade Kubernetes clusters (e.g., EKS, GKE, AKS). Writing Helm charts, implementing GitOps with ArgoCD, and configuring service meshes (e.g., Istio). | Decouples applications from underlying infrastructure, improving portability and resource efficiency. Simplifies management of complex microservices architectures. |

Understanding these technical functions allows you to engage potential partners with a precise problem statement, whether it's reducing pipeline execution time or implementing a cost-effective multi-tenant Kubernetes architecture.

Accelerate Your Time to Market

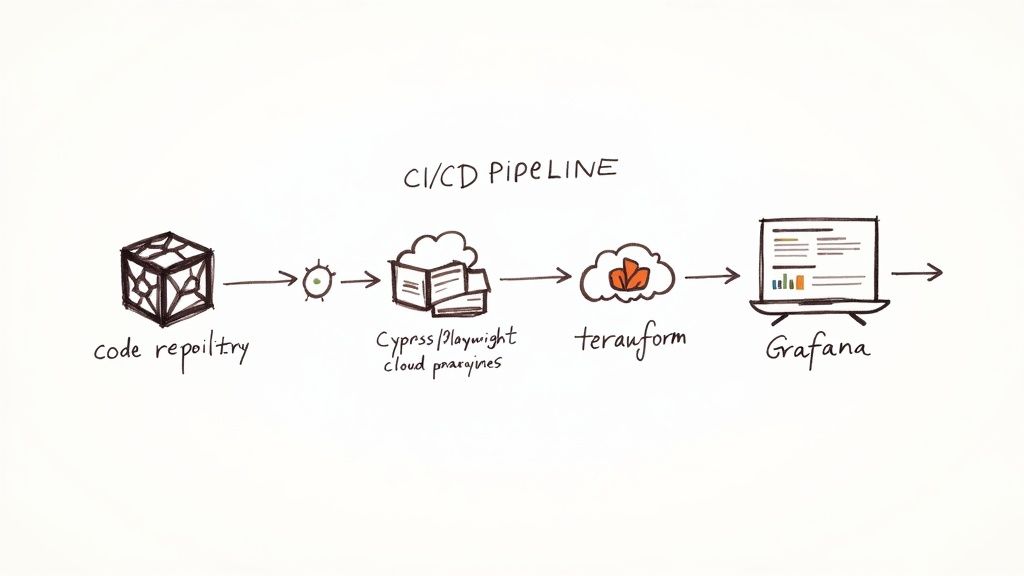

A primary technical objective is to reduce the "commit-to-deploy" time. Consultants achieve this by architecting efficient Continuous Integration and Continuous Deployment (CI/CD) pipelines.

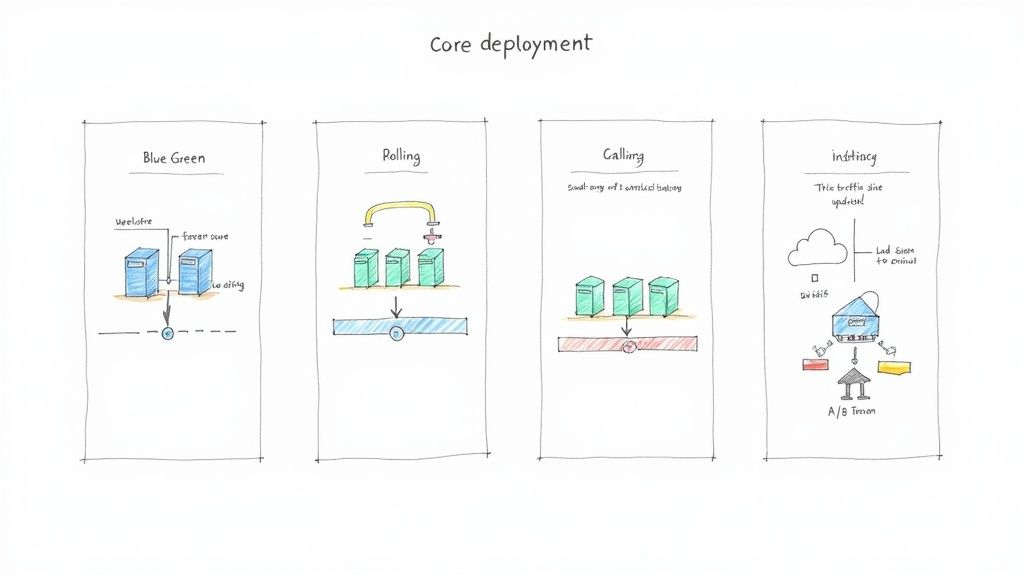

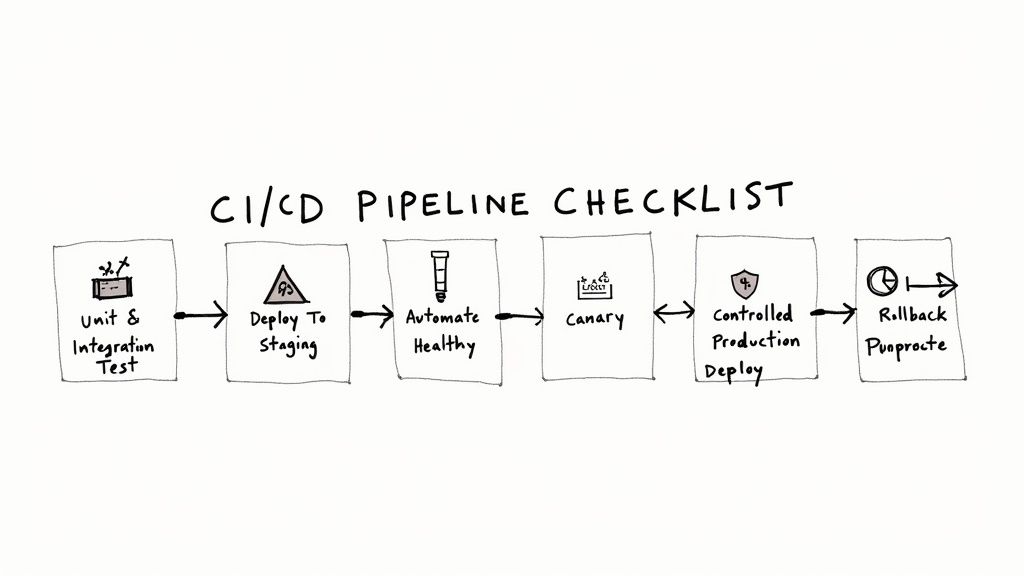

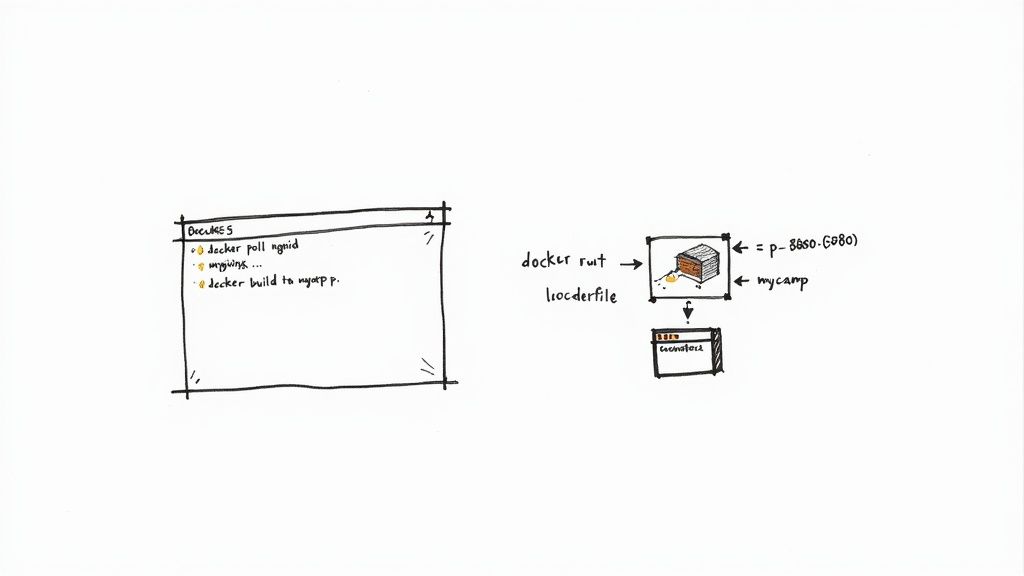

Instead of a manual release process involving SSH, shell scripts, and manual verification, they implement fully automated, declarative pipelines. For example, a consultant might replace a multi-day manual release with a GitLab CI pipeline that automatically builds a container, runs unit and integration tests in parallel jobs, scans the image for vulnerabilities, and performs a canary deployment to Kubernetes in under 15 minutes. This drastically shortens the feedback loop for developers and accelerates feature velocity.

Embed Security into the Lifecycle

DevSecOps is the practice of integrating automated security controls directly into the CI/CD pipeline, making security a shared responsibility. An experienced consultant implements this by adding specific stages to your pipeline.

A consultant’s value isn't just in the tools they implement, but in the cultural shift they catalyze. They are external change agents who can bridge the developer-operator divide and foster a shared sense of ownership over the entire delivery process.

This technical implementation typically includes:

- Static Application Security Testing (SAST): Scans source code for vulnerabilities (e.g., SQL injection, XSS) using tools like SonarQube, integrated as a blocking step in a merge request pipeline.

- Dynamic Application Security Testing (DAST): Tests the running application in a staging environment to find runtime vulnerabilities by simulating attacks.

- Software Composition Analysis (SCA): Uses tools like Snyk or Trivy to scan package manifests (

package.json,requirements.txt) for known CVEs in third-party libraries.

By embedding these checks as automated quality gates, security becomes a proactive, preventative measure, not a reactive bottleneck.

Build a Scalable Cloud Native Foundation

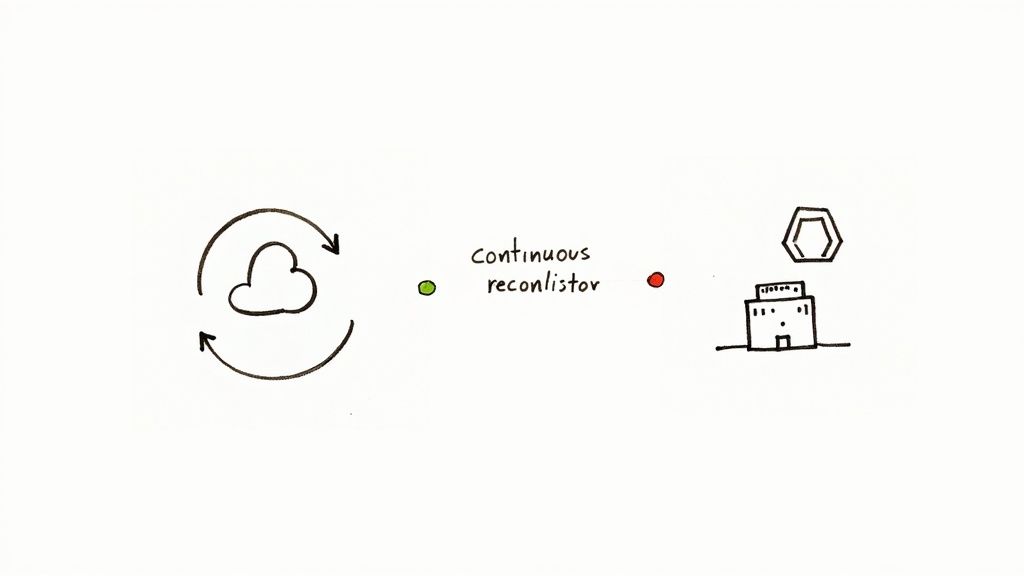

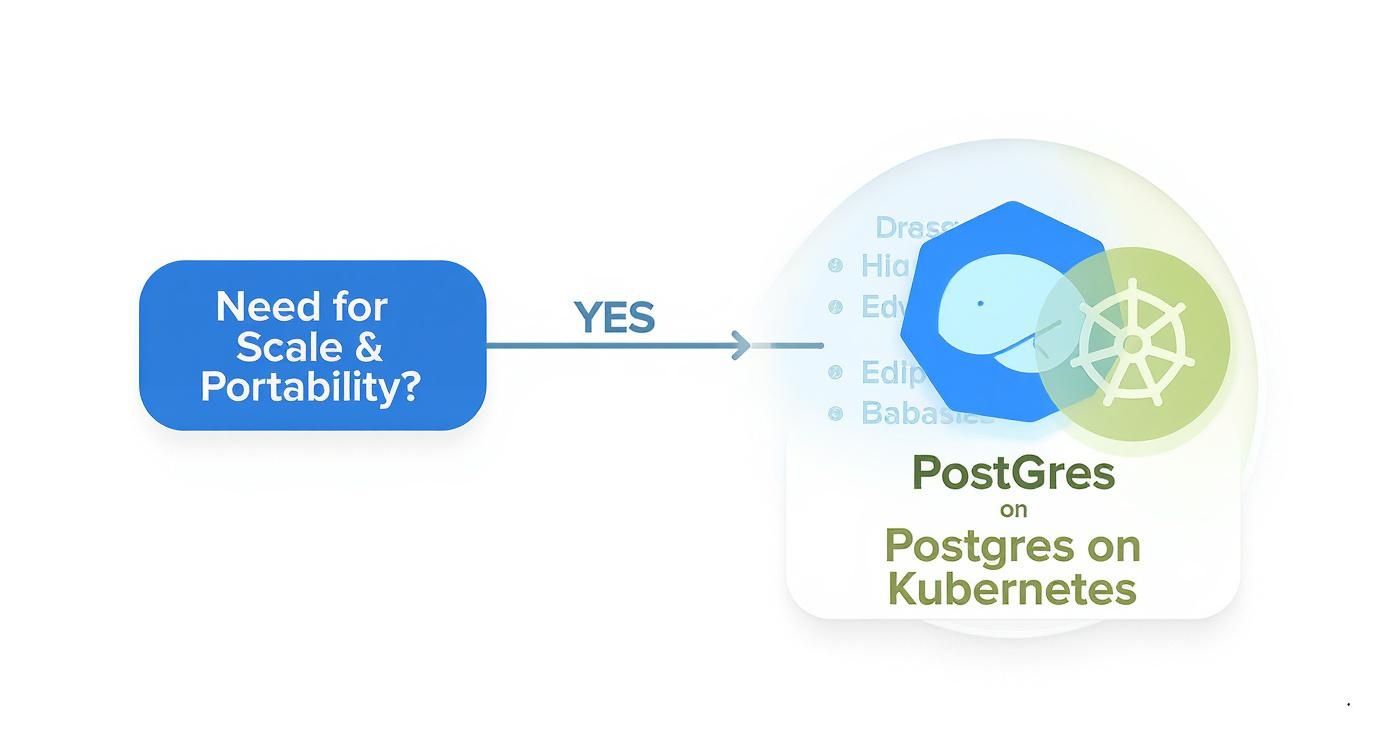

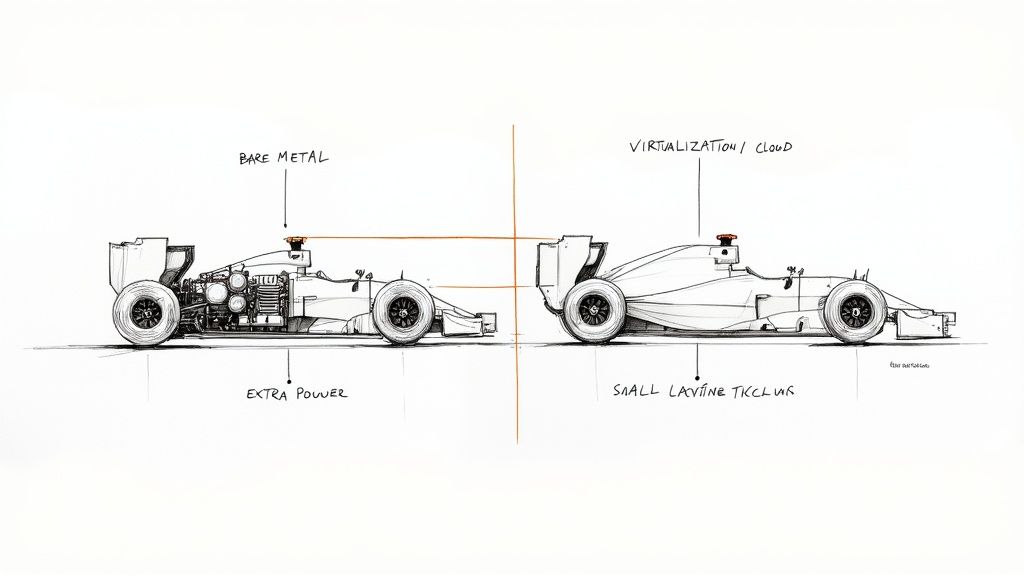

As services scale, the underlying infrastructure must scale elastically without manual intervention. DevOps consultants design cloud-native architectures using technologies like Kubernetes, serverless functions, and Infrastructure as Code (IaC). Using Terraform, they define all infrastructure components—from VPCs and subnets to Kubernetes clusters and IAM roles—in version-controlled code.

This IaC approach ensures environments are identical and reproducible, eliminating "it works on my machine" issues. Furthermore, documenting this infrastructure via code is a core tenet and complements the benefits of a knowledge management system. This practice prevents knowledge silos and streamlines the onboarding of new engineers by providing a single source of truth for the entire system architecture.

How to Vet Your Ideal DevOps Partner

Selecting the right DevOps consulting company requires moving beyond marketing collateral and conducting a rigorous technical evaluation. Your goal is to probe their real-world, hands-on expertise by asking specific, scenario-based questions that reveal their problem-solving methodology and depth of knowledge.

The vetting process should feel like a system design interview. You need a partner who can architect solutions for your specific technical challenges, not just recite generic DevOps principles.

Probing Their Infrastructure as Code Expertise

Proficiency in Infrastructure as Code (IaC) is non-negotiable. A simple "Do you use Terraform?" is insufficient. You must validate the sophistication of their approach.

Begin by asking how they structure Terraform code for multi-environment deployments (dev, staging, production). A competent response will involve strategies like using Terragrunt for DRY configurations, a directory-based module structure (/modules, /environments), or Terraform workspaces. They should be able to articulate how they manage environment-specific variables and prevent configuration drift.

A true sign of an experienced DevOps firm is how they handle failure. Ask them to walk you through a time a tricky

terraform applywent sideways and how they fixed it. Their story will tell you everything you need to know about their troubleshooting chops and whether they prioritize safe, incremental changes.

Drill down on their state management strategy. Ask how they handle remote state. The correct answer involves using a remote backend like Amazon S3 coupled with a locking mechanism like DynamoDB to prevent concurrent state modifications and corruption. This is a fundamental best practice that separates amateurs from professionals.

Evaluating Their Container Orchestration and CI/CD Philosophy

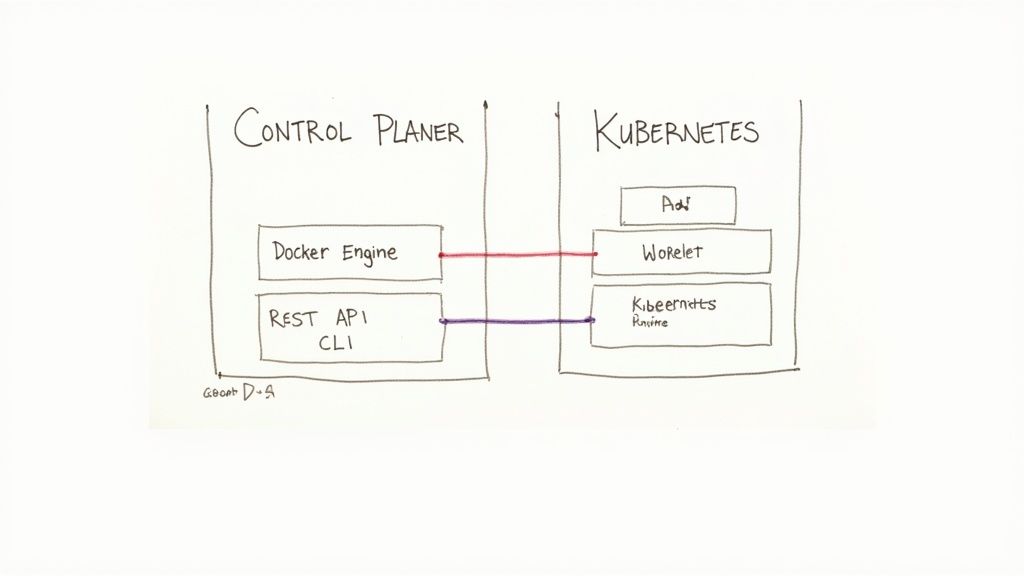

Containerization with Docker and orchestration with Kubernetes are central to modern cloud-native systems. Your partner must demonstrate deep, practical experience.

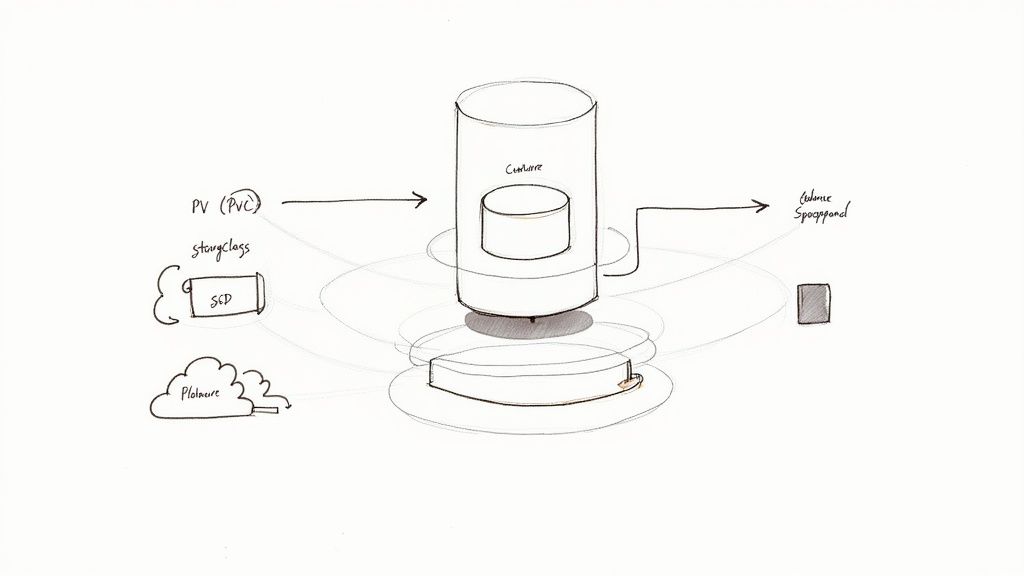

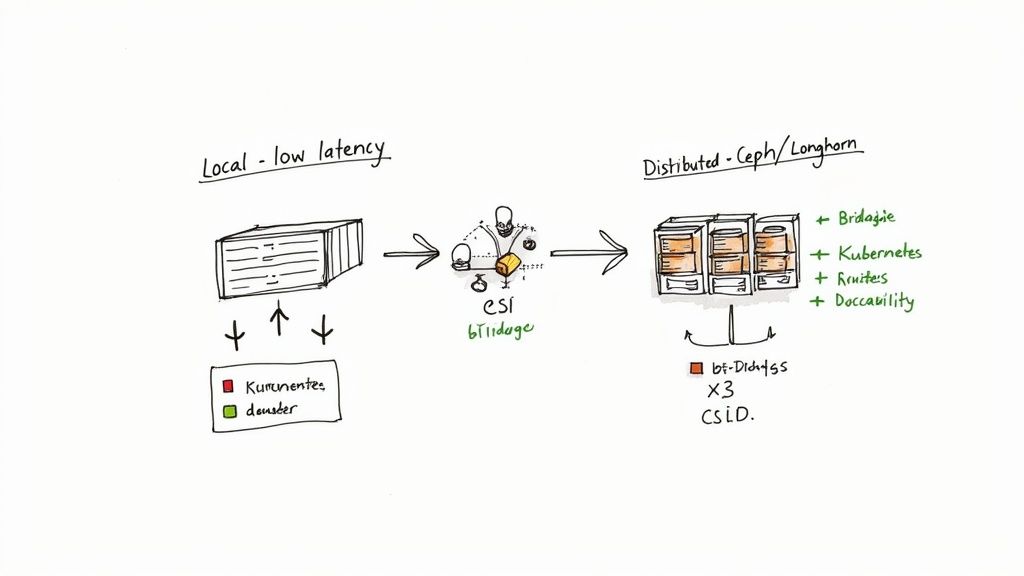

Ask them to describe a complex Kubernetes deployment they've managed. Probe for details on their approach to ingress controllers, service mesh implementation for mTLS, or strategies for managing persistent storage with StorageClasses and PersistentVolumeClaims. Discuss specifics like network policies for pod-to-pod communication or RBAC configuration for securing the Kubernetes API. A competent team will provide detailed anecdotes.

Then, pivot to their CI/CD methodology. "We use Jenkins" is not an answer. Go deeper with technical questions:

- How do you optimize pipeline performance for both speed and resource usage? Look for answers involving multi-stage Docker builds, caching dependencies (e.g., Maven/.npm directories), and running test suites in parallel jobs.

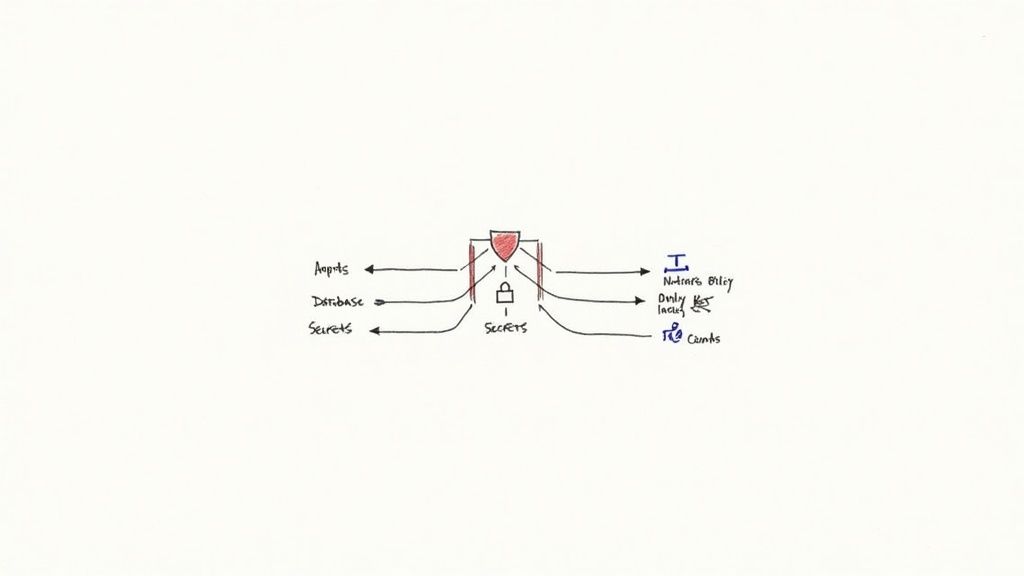

- How do you secure secrets within a CI/CD pipeline? A strong answer will involve fetching credentials at runtime from a secret manager like HashiCorp Vault or AWS Secrets Manager, rather than storing them as environment variables in the CI tool.

- Describe a scenario where you would choose GitHub Actions over GitLab CI, and vice versa. A seasoned consultant will discuss trade-offs related to ecosystem integration, runner management, and feature sets (e.g., GitLab's integrated container registry and security scanning).

A rigid, "one-tool-fits-all" mindset is a major red flag. True experts tailor their toolchain recommendations to the client's existing stack, team skills, and specific technical requirements. For more on what separates the best from the rest, check out our detailed guide on leading DevOps consulting companies.

Uncovering Technical and Strategic Red Flags

During these technical discussions, be vigilant for indicators of shallow expertise. Vague answers or an inability to substantiate claims with specific examples are warning signs.

Here are three critical red flags:

- Buzzwords Without Implementation Details: If they use terms like "shift left" but cannot detail how they would integrate a SAST tool into a GitLab merge request pipeline to act as a quality gate, they lack practical experience. Challenge them to describe a specific vulnerability class they've mitigated with an automated security control.

- Ignorance of DORA Metrics: Elite DevOps consultants are data-driven. If they cannot hold a detailed conversation about measuring and improving the four key DORA metrics—Deployment Frequency, Lead Time for Changes, Mean Time to Recovery, and Change Failure Rate—they are likely focused on completing tasks, not delivering measurable outcomes.

- Inability to Discuss Technical Trade-offs: Every engineering decision involves compromises. Ask why they might choose Pulumi (using general-purpose code) over Terraform (using HCL), or an event-driven serverless architecture over a Kubernetes-based one for a specific workload. A partner who cannot articulate the pros and cons of different technologies lacks the deep expertise required for complex system design.

Understanding Engagement Models and Pricing Structures

To avoid scope creep and budget overruns, you must understand the contractual and financial frameworks used by consulting firms. The engagement model directly influences risk, flexibility, and total cost of ownership (TCO). Misalignment here often leads to friction and missed technical objectives.

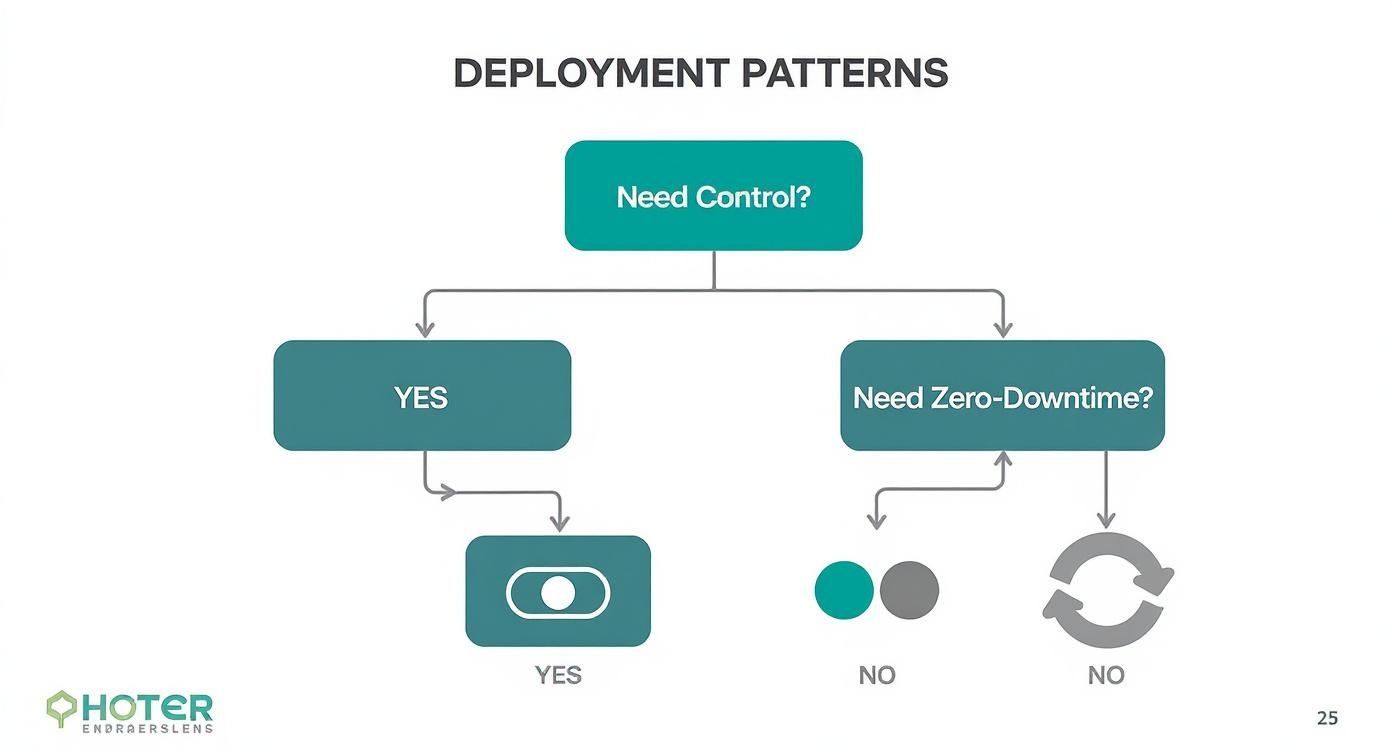

The optimal model depends on your technical goals. Are you executing a well-defined migration project? Do you need ongoing operational support for a production system? Or are you looking to embed a specialist to upskill your team? Each scenario has distinct financial and technical implications.

Project-Based Engagements

This is a fixed-scope, fixed-price model centered on a specific, time-bound deliverable. The scope of work (SOW), timeline, and total cost are agreed upon upfront.

- Technical scenario: A company needs to build a CI/CD pipeline for a microservice. The deliverable is a production-ready GitLab CI pipeline that builds a Docker image, runs tests, and deploys to an Amazon EKS cluster via a Helm chart. The engagement concludes upon successful deployment and delivery of documentation.

- The upside: High budget predictability. The cost is known, simplifying financial planning.

- The downside: Inflexibility. If new technical requirements emerge mid-project, a formal change order is required, leading to renegotiation, delays, and increased costs.

The success of a project-based engagement is entirely dependent on the technical specificity of the Statement of Work (SOW). Scrutinize it for precise definitions of "done," explicit deliverables (e.g., "Terraform modules for the VPC, subnets, NAT Gateways, and EKS cluster"), and payment milestones tied to concrete technical achievements. An ambiguous SOW is a recipe for conflict.

Retainers and Managed Services

For continuous operational support, a retainer or managed services model is more appropriate. This model is effectively outsourcing the day-to-day management of your DevOps functions.

This is the core of DevOps as a Service. It provides ongoing access to a team of experts for tasks like pipeline maintenance, cloud cost optimization, security patching, and incident response, without the overhead of hiring additional full-time engineers.

- Technical scenario: An established SaaS company requires 24/7 SRE support for its production Kubernetes environment. This includes proactive monitoring with Prometheus/Alertmanager, managing SLOs/SLIs, responding to incidents, and performing regular cluster upgrades and security patching. A managed services agreement guarantees expert availability.

- The upside: Predictable monthly operational expenditure (OpEx) and guaranteed access to specialized skills for maintaining system reliability and security.

- The downside: Can be more costly than a project-based model if your needs are intermittent. You are paying for guaranteed availability, not just hours worked.

Staff Augmentation

Staff augmentation involves embedding one or more consultants directly into your engineering team. They operate under your direct management to fill a specific skill gap or provide additional bandwidth for a critical project.

This is not outsourcing a function, but rather acquiring specialized technical talent on a temporary basis. The consultant joins your daily stand-ups, participates in sprint planning, and commits code to your repositories just like a full-time employee.

- Technical scenario: Your platform team is adopting a service mesh but lacks deep expertise in Istio. You bring in a consultant to lead the implementation of mTLS and traffic shifting policies, and, crucially, to pair-program with and mentor your internal team on Istio's configuration and operational management.

- The upside: Maximum flexibility and deep integration. You get the precise skills needed and retain full control over the consultant's day-to-day priorities.

- The downside: Typically the highest hourly cost. It also requires significant management overhead from your engineering leads to direct their work and integrate them effectively.

How to Measure Success: Metrics and SLAs That Actually Matter

Vague goals like "improved efficiency" are insufficient to justify the investment in a DevOps consulting company. To measure ROI, you must use quantifiable technical metrics and enforce them with a stringent Service Level Agreement (SLA). This data-driven approach transforms ambiguous objectives into trackable outcomes.

The market demand for such measurable results is intense; the global DevOps market is projected to grow from $18.11 billion in 2025 to $175.53 billion by 2035, a surge fueled by organizations demanding tangible performance improvements.

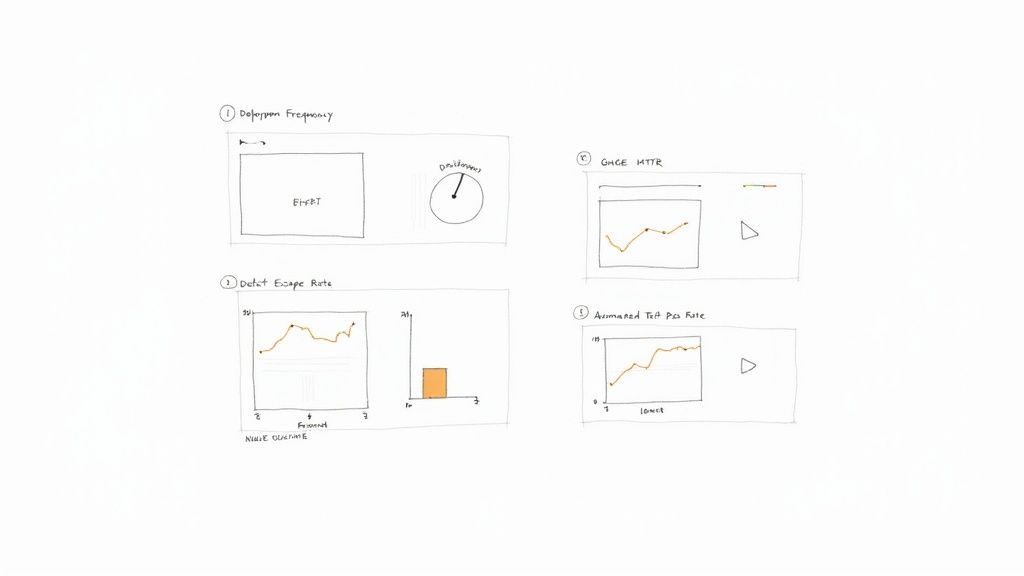

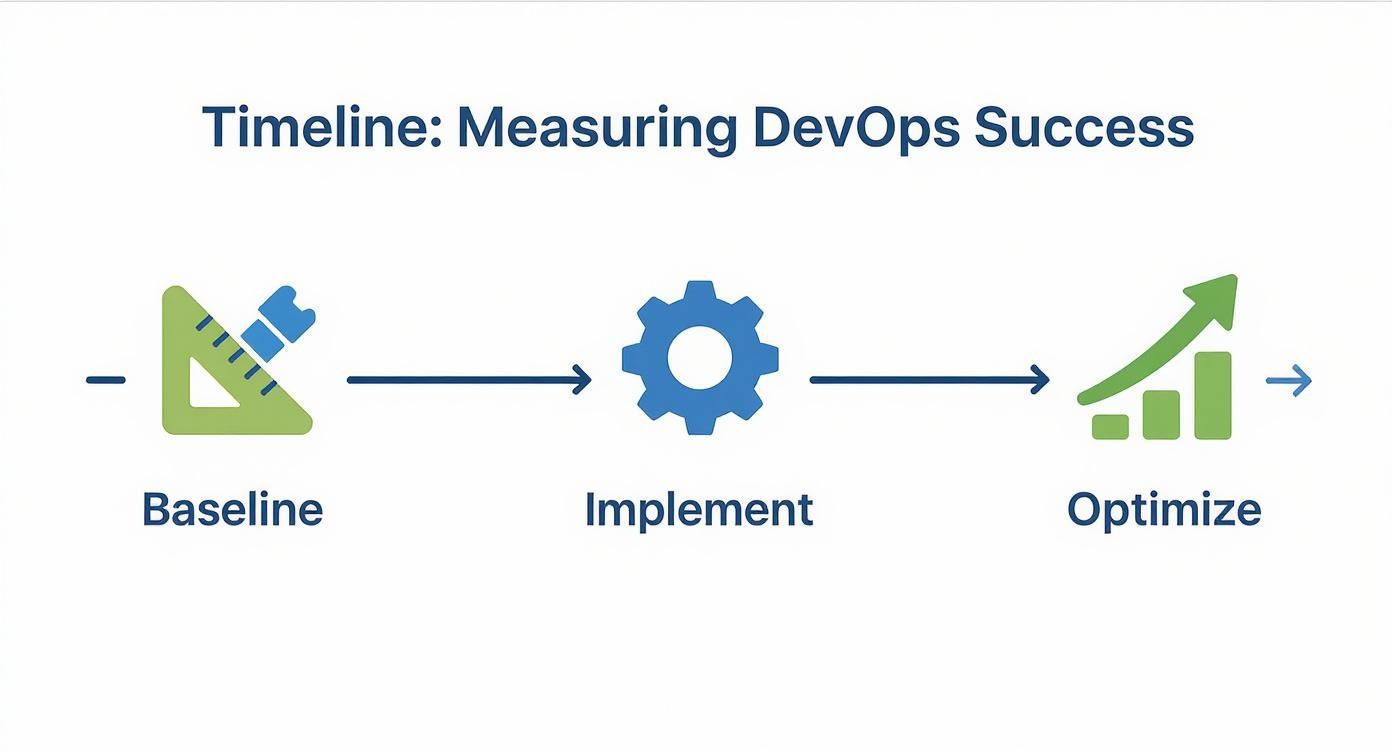

First, Get a Baseline with DORA Metrics

Before any implementation begins, a baseline of your current performance is essential. The industry standard for measuring software delivery performance is the set of four DORA (DevOps Research and Assessment) metrics.

Any credible consultant will begin by establishing these baseline measurements:

- Deployment Frequency: How often does code get successfully deployed to production? Elite performers deploy on-demand, multiple times a day.

- Lead Time for Changes: What is the median time from a code commit to it running in production? This is a key indicator of pipeline efficiency.

- Mean Time to Recovery (MTTR): How long does it take to restore service after a production failure? This directly measures system resilience.

- Change Failure Rate: What percentage of deployments to production result in a degradation of service and require remediation? This measures release quality and stability.

Tracking these metrics provides objective evidence of whether the consultant's interventions are improving engineering velocity and system stability.

Go Beyond DORA to Business-Focused KPIs

While DORA metrics are crucial for engineering health, success also means linking technical improvements to business outcomes. The engagement agreement should include specific targets for KPIs that impact the bottom line.

A great SLA isn't just a safety net for when things go wrong; it's a shared roadmap for what success looks like. It aligns your business goals with the consultant's technical work, making sure everyone is rowing in the same direction.

Here are some examples of technical KPIs with business impact:

- Infrastructure Cost Reduction: Set a quantitative target, such as "Reduce monthly AWS compute costs by 15%" by implementing EC2 Spot Instances for stateless workloads, rightsizing instances, and enforcing resource tagging for cost allocation.

- Build and Deployment Times: Define a specific performance target for the CI/CD pipeline, such as "Reduce the average p95 build-to-deploy time from 20 minutes to under 8 minutes."

- System Uptime and Availability: Define availability targets with precision, such as "Achieve 99.95% uptime for the customer-facing API gateway," measured by an external monitoring tool and excluding scheduled maintenance windows.

Crafting an SLA That Has Teeth

The SLA is the contractual instrument that formalizes these metrics. It must be specific, measurable, and unambiguous. For uptime and disaster recovery, this includes implementing robust technical solutions, such as strategies for multi-provider failover reliability.

A strong, technical SLA should define:

- Response Times: Time to acknowledge an alert, tied to severity. A "Severity 1" (production outage) incident should mandate a response within 15 minutes.

- Resolution Times: Time to resolve an issue, also tied to severity.

- Availability Guarantees: The specific uptime percentage (e.g., 99.9%) and a clear, technical definition of "downtime" (e.g., 5xx error rate > 1% over a 5-minute window).

- Severity Level Definitions: Precise, technical criteria for what constitutes a Sev-1, Sev-2, or Sev-3 incident.

- Reporting and Communication: Mandated frequency of reporting (e.g., weekly DORA metric dashboards) and defined communication protocols (e.g., a dedicated Slack channel).

These metrics are foundational to Site Reliability Engineering. To explore how SRE principles can enhance system resilience, see our guide on service reliability engineering.

Your First 90 Days with a DevOps Consultant

The initial three months of an engagement are critical for setting the trajectory of the partnership. A structured, technical onboarding process is essential for achieving rapid, tangible results. This involves a methodical progression from system discovery and access provisioning to implementing foundational automation and delivering measurable improvements.

This focus on rapid, iterative impact is a key driver of the DevOps market, which saw growth from an estimated $10.46 billion to $15.06 billion in a single year. These trends are explored in-depth in Baytech Consulting's analysis of the state of DevOps in 2025.

A successful 90-day plan should follow a logical, phased approach: Baseline, Implement, and Optimize.

This structured methodology ensures that solutions are built upon a thorough understanding of the existing environment, preventing misguided efforts and rework.

Kicking Things Off: The Discovery Phase

The first two weeks are dedicated to deep technical discovery. The objectives are to provision secure access, conduct knowledge transfer sessions, and perform a comprehensive audit of existing systems and workflows.

Your onboarding checklist must include:

- Scoped Access Control: Grant initial read-only access using dedicated IAM roles. This includes code repositories (GitHub, GitLab), cloud provider consoles (AWS, GCP, Azure), and CI/CD systems. Adherence to the principle of least privilege is non-negotiable; never grant broad administrative access on day one.

- Architecture Review Sessions: Schedule technical deep-dives where your engineers walk the consultants through system architecture diagrams, data flow, network topology, and current deployment processes.

- Toolchain and Dependency Mapping: The consultants should perform an audit to map all tools, libraries, and service dependencies to identify bottlenecks, security vulnerabilities, and single points of failure.

- DORA Metrics Baseline: Establish the initial measurements for Deployment Frequency, Lead Time for Changes, Mean Time to Recovery (MTTR), and Change Failure Rate to serve as the benchmark for future improvements.

One of the biggest mistakes I see teams make is holding back information during onboarding. Be brutally honest about your technical debt and past failures. The more your consultants know about the skeletons in the closet, the faster they can build solutions that actually fit your reality, not just some generic template.

The implementation roadmap will vary significantly based on your company's maturity. A startup requires foundational infrastructure, while an enterprise often needs to modernize legacy systems.

Sample Roadmap for a Startup

For a startup, the first 90 days are focused on establishing a scalable, automated foundation to support rapid product development. The goal is to evolve from manual processes to a robust CI/CD pipeline.

Here is a practical, phased 90-day plan for a startup:

| Phase | Timeline | Key Technical Objectives | Success Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foundation (IaC) | Weeks 1-2 | – Audit existing cloud resources – Codify core network infrastructure (VPC, subnets, security groups) using Terraform modules – Establish a Git repository with protected branches for IaC |

– 100% of core infrastructure managed via version-controlled code – Ability to provision a new environment from scratch in < 1 hour |

| CI Implementation | Weeks 3-4 | – Configure self-hosted or cloud-based CI runners (GitHub Actions, etc.) – Implement a CI pipeline that triggers on every commit to main, automating build and unit tests– Integrate SAST and linting as blocking jobs |

– Build success rate >95% on main– Average CI pipeline execution time < 10 minutes |

| Staging Deployments | Weeks 5-8 | – Write a multi-stage Dockerfile for the primary application – Provision a separate staging environment using the Terraform modules – Create a CD pipeline to automatically deploy successful builds from main to staging |

– Fully automated, zero-touch deployment to staging – Staging environment accurately reflects production configuration |

| Production & Observability | Weeks 9-12 | – Implement a Blue/Green or canary deployment strategy for production releases – Instrument the application and infrastructure with Prometheus metrics – Set up a Grafana dashboard for key SLIs (latency, error rate, saturation) |

– Zero-downtime production deployments executed via pipeline – Actionable alerts configured for production anomalies |

This roadmap provides a clear technical path from manual operations to an automated, observable, and scalable platform.

Sample Roadmap for an Enterprise

For an enterprise, the challenge is typically modernizing a legacy monolithic application by containerizing it and deploying it to a modern orchestration platform.

Weeks 1-4: Kubernetes Foundation and Application Assessment

The initial phase involves provisioning a production-grade Kubernetes cluster (e.g., EKS, GKE) using Terraform. Concurrently, consultants perform a detailed analysis of the legacy application to identify dependencies, configuration parameters, and stateful components, creating a containerization strategy.

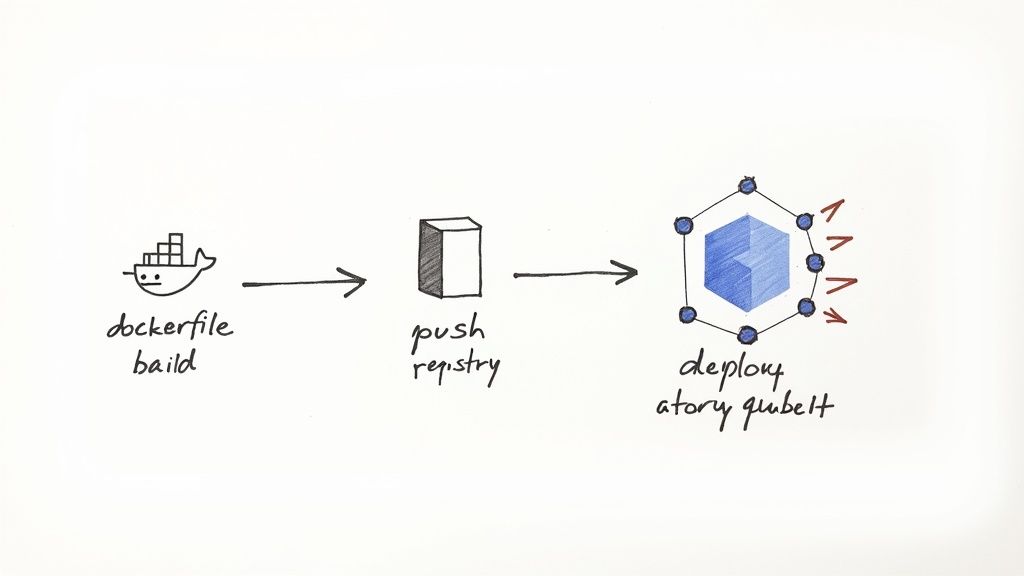

Weeks 5-8: Containerization and CI Pipeline Integration

The team develops a Dockerfile to containerize the legacy application, externalizing configuration and handling stateful data. They then build a CI pipeline in a tool like Jenkins or GitLab CI that compiles the code, builds the Docker image, and pushes the versioned artifact to a container registry (e.g., ECR, GCR). This pipeline must include SCA scanning of the final image for known CVEs.

Weeks 9-12: Staging Deployment and DevSecOps Integration

With a container image available, the team writes Kubernetes manifests (Deployments, Services, ConfigMaps, Secrets) or a Helm chart to deploy the application into a staging namespace on the Kubernetes cluster. The CD pipeline is extended to automate this deployment. Crucially, this stage integrates Dynamic Application Security Testing (DAST) against the running application in staging as a final quality gate before a manual promotion to production can occur.

Your Questions, Answered

When evaluating a DevOps consulting firm, several key questions consistently arise regarding cost, security, and knowledge transfer. Here are direct, technical answers.

How Much Does a DevOps Consulting Company Cost?

Pricing is determined by the engagement model, scope complexity, and the seniority of the consultants. Here are typical cost structures:

- Hourly Rates: Ranging from $150 to over $350 per hour. This model is suitable for staff augmentation or advisory roles where the scope is fluid.

- Project-Based Pricing: For a defined outcome, such as a complete Terraform-based AWS infrastructure build-out, expect a fixed price between $20,000 and $100,000+. The cost scales with complexity (e.g., multi-region, high availability, compliance requirements).

- Retainer/Managed Services: For ongoing SRE and operational support, monthly retainers typically range from $5,000 to $25,000+, depending on the scope of services (e.g., 24/7 incident response vs. business hours support) and the size of the infrastructure.

A critical mistake is optimizing solely for the lowest hourly rate. A senior consultant at a higher rate who correctly architects and automates your infrastructure in one month provides far greater value than a junior consultant who takes three months and introduces technical debt. Evaluate based on total cost of ownership and project velocity.

How Do You Handle Security and Access to Our Systems?

Security must be paramount. A request for root or administrative credentials on day one is a major red flag. A professional firm will adhere strictly to the principle of least privilege.

A secure access protocol involves:

- Dedicated IAM Roles: The consultant will provide specifications for you to create custom IAM (Identity and Access Management) roles with narrowly scoped permissions. Initial access is often read-only, with permissions escalated as needed for specific tasks.

- No Shared Credentials, Ever: Each consultant must be provisioned with a unique, named account tied to their identity. This is fundamental for accountability and auditability.

- Secure Secret Management: They will advocate for and use a dedicated secrets management solution like HashiCorp Vault or a cloud-native service (e.g., AWS Secrets Manager). Credentials, API keys, and certificates must never be hardcoded or stored in Git.

What Happens After the Engagement Ends?

A primary objective of a top-tier DevOps consultant is to make themselves redundant. The goal is to build robust systems and upskill your team, not to create a long-term dependency.

A professional offboarding process must include:

- Thorough Documentation: While Infrastructure as Code (Terraform, etc.) is largely self-documenting, the consultant must also provide high-level architecture diagrams, decision logs, and operational runbooks for incident response and routine maintenance.

- Knowledge Transfer Sessions: The consultants should conduct technical walkthroughs and pair-programming sessions with your engineers. The objective is to transfer not just the "how" (operational procedures) but also the "why" (the architectural reasoning behind key decisions).

- Ongoing Support Options: Many firms offer a post-engagement retainer for a block of hours. This provides a valuable safety net for ad-hoc support as your team assumes full ownership.

This focus on empowerment is what distinguishes a true strategic partner from a temporary contractor. The ultimate success is when your internal team can confidently operate, maintain, and evolve the systems the consultants helped build.

Ready to accelerate your software delivery with proven expertise? At OpsMoon, we connect you with the top 0.7% of global DevOps talent. Start with a free work planning session to map your roadmap to success. Find your expert today.