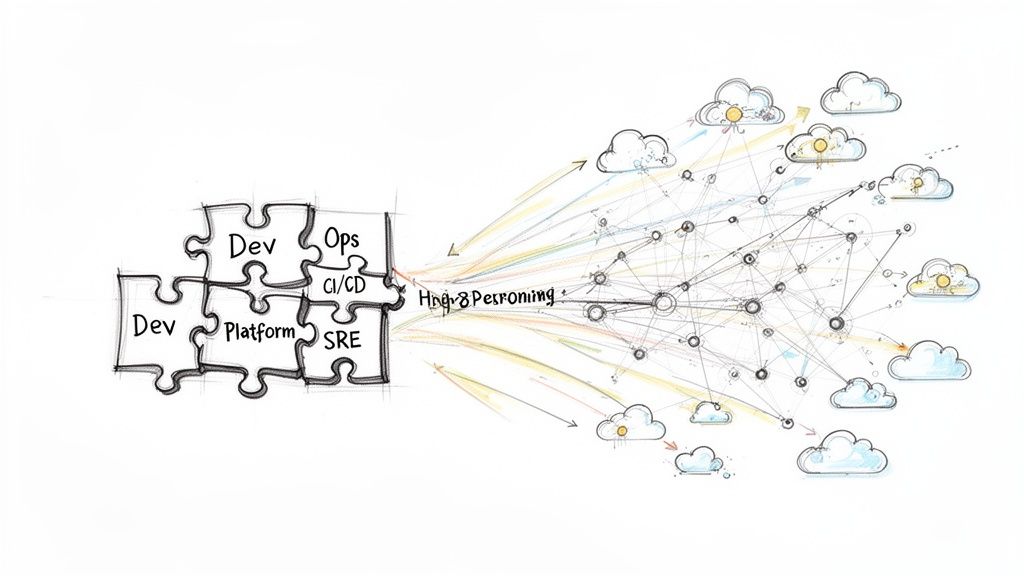

Building a functional DevOps team structure isn't about slapping new job titles on an org chart. It's about re-architecting the flow of work and information between development and operations to accelerate software delivery. The goal is a cross-functional unit that owns a service's entire lifecycle, from the first line of code committed to main to its performance in production.

From Siloed Departments to Collaborative Squads

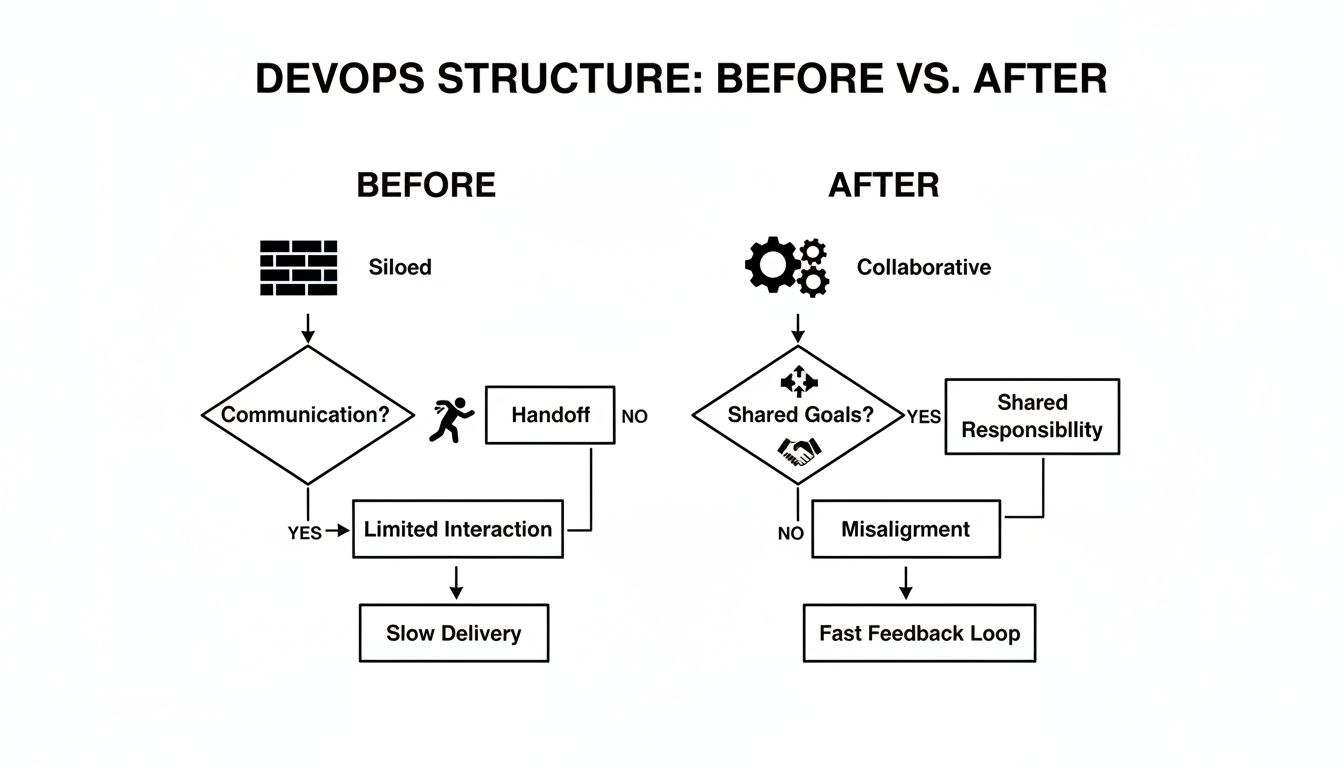

Before DevOps became the standard, the software delivery lifecycle was a classic waterfall handoff. Developers, incentivized by feature velocity, would write code, run unit tests, and then "throw it over the wall" to a separate Operations team. Ops, incentivized by stability and uptime, would receive this code—often with minimal context—and face the complex task of deploying and maintaining it.

This "throw it over the wall" approach was a recipe for technical and cultural debt. It created fundamental conflicts: developers were measured on change, while operations were measured on stability. This misalignment resulted in a culture poisoned by bottlenecks, blame games during outages, and release cycles that took weeks or months. The business demanded faster iteration, but the organizational structure created an unbreakable bottleneck.

The Foundational Shift to Shared Ownership

The core principle of DevOps is to dismantle this broken assembly line. Instead of two warring departments, you build a single, integrated team with shared accountability for both feature development and operational reliability. Developers, SREs, and platform engineers work collaboratively, unified by shared objectives (SLOs) and shared responsibility for the entire software lifecycle. This cultural shift is the non-negotiable foundation of any effective DevOps team structure.

The results are not merely incremental; they are transformative. High-performing DevOps teams deploy 973 times more frequently and recover from incidents an incredible 6,570 times faster than their low-performing peers. That performance gap isn't magic—it's the direct result of structuring teams around shared goals, automated workflows, and rapid feedback loops. For more on where top tech leaders are heading, check out the 2026 DevOps forecast.

Why Breaking Down Walls Matters

This isn't just about reorganizing reporting lines. It’s about fundamentally re-architecting how technical work is planned, executed, and maintained. To make this leap from siloed departments to truly collaborative squads, you have to implement rigorous team collaboration best practices.

When you reframe the relationship between Dev and Ops from a handoff to a partnership, you empower teams to own their work from concept to customer. This shared ownership creates tight feedback loops—like developers seeing production performance metrics directly in their dashboards—driving up quality and making the connection between engineering work and business value explicit.

This deep integration of skills is a core tenet of Agile methodologies. The tight feedback loops and iterative nature of DevOps are the technical realization of Agile principles. You can learn more about how these two ideas feed each other in our guide on the relationship between Agile and DevOps. Understanding this foundational concept is critical before analyzing the specific architectural models for your teams.

Analyzing Common DevOps Team Models

Selecting a DevOps team structure isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution. The optimal topology for a large enterprise like Netflix, with a mature platform engineering group, would cripple a 20-person startup that needs maximum agility. The right model depends on your company’s scale, technical maturity, product complexity, and existing engineering culture. Choosing incorrectly introduces more friction, not less.

The objective is to eliminate the "throw it over the wall" anti-pattern and move toward a collaborative workflow with shared ownership.

This diagram illustrates the fundamental shift. It contrasts the siloed "before" state—with its distinct handoffs and communication barriers—with the integrated "after" state, where a unified team shares responsibility for the entire value stream. That transformation is the goal of any structure we explore.

Let's dissect the common topologies, from well-known anti-patterns to the highly-leveraged models used by elite engineering organizations.

Comparison of DevOps Team Structure Models

To make an informed decision, you must analyze the trade-offs of each model. What provides velocity for a small team may create chaos at scale. This table outlines the core characteristics, pros, cons, and ideal implementation scenarios for the most prevalent structures.

| Structure Model | Key Characteristic | Pros | Cons | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DevOps as a Silo | A separate team manages all DevOps tooling (CI/CD, IaC, monitoring). | Centralizes tool expertise. | Becomes a new bottleneck; reinforces "us vs. them" culture; slows down delivery. | Not recommended (it's an anti-pattern). |

| Embedded DevOps | A DevOps or SRE is assigned directly to a specific product team. | Extremely tight feedback loops; context-specific automation; high velocity. | Inefficient at scale; can lead to inconsistent tooling and practices across teams. | Startups, small companies, or project teams piloting a new service. |

| SRE Model | Operations is treated as a software problem, managed by engineers who code. | Data-driven reliability via SLOs/Error Budgets; balances feature dev with stability. | Requires high engineering maturity and a data-first culture; can be difficult to hire for. | Companies with business-critical services where uptime is non-negotiable (e.g., fintech, e-commerce). |

| Platform Team | A central team builds and maintains a self-service Internal Developer Platform (IDP). | High leverage and consistency at scale; reduces developer cognitive load. | High initial investment; risk of becoming a new silo if not run as an internal product. | Mature organizations with many development teams and complex microservice architectures. |

Understanding these trade-offs is the first step. Now, let's dive into the technical implementation details of each model.

The DevOps as a Silo Anti-Pattern

One of the most common and damaging mistakes is to rebrand the old Operations team as the "DevOps Team." This is a classic anti-pattern because it preserves the core problem: the handoff. It fails to shift responsibility and ownership.

In this broken model, developers still push their code to a boundary. The only change is that it now lands with a "DevOps Team" that manages the CI/CD pipelines, Terraform scripts, and Kubernetes manifests. This new silo becomes a central bottleneck, and developers find themselves filing tickets and waiting for "DevOps" to fix a broken pipeline or provision new infrastructure, just as they did with the old Ops team.

Key Takeaway: If your "DevOps team" is a service desk that other engineers file tickets against, you haven't adopted DevOps. You've just rebranded a silo. True DevOps distributes operational responsibility, empowering development teams to own their services from code to production.

This structure is doomed to fail because it perpetuates the "us vs. them" mindset and prevents developers from gaining the operational context needed to build truly resilient and observable systems.

The Embedded DevOps Model

A significantly more effective approach, especially for smaller organizations or those early in their DevOps transformation, is the Embedded DevOps model. The implementation is straightforward: one or more DevOps or Site Reliability Engineers (SREs) are integrated directly into a product development team.

This embedded engineer acts as a force multiplier, not a gatekeeper. Their primary function is to enable the team by building context-specific automation and upskilling developers in operational best practices. They don't "do the ops work"; they make the ops work easy for developers.

Actionable Responsibilities of an Embedded Engineer:

- Pipeline Automation: Build and maintain the CI/CD pipeline for the team's specific microservice, often using tools like GitHub Actions or GitLab CI, with stages for linting, static analysis, unit/integration testing, container scanning, and deployment.

- Infrastructure as Code (IaC): Develop and manage the Terraform or Pulumi modules for the team's infrastructure (e.g., databases, caches, queues), ensuring it's version-controlled and auditable.

- Mentorship & Enablement: Teach developers how to instrument their code with structured logging (e.g., JSON format), define meaningful SLOs, and build effective monitoring dashboards in Grafana.

- Toil Reduction: Identify and automate repetitive manual tasks, such as certificate rotation or database backups, freeing up developer time for feature work.

This model creates extremely tight feedback loops, ensuring that operational requirements are engineered into the product from the start, not retrofitted after an outage.

The Site Reliability Engineering (SRE) Model

Pioneered by Google, the SRE model operationalizes the principle of "treating operations as a software engineering problem." SRE teams are composed of engineers with strong software development skills who are tasked with ensuring a service meets its defined Service Level Objectives (SLOs).

In this model, the SRE team shares ownership of production services with the development team. They have the authority to halt new feature deployments if reliability targets are breached or if the operational workload (toil) exceeds predefined limits (typically 50% of their time).

This structure is governed by a data-driven contract:

- Define SLOs: The product and SRE teams collaboratively define measurable reliability targets, such as 99.95% API request success rate over a rolling 28-day window.

- Establish Error Budgets: The remaining 0.05% becomes the "error budget"—the acceptable level of failure. This budget quantifies the risk the business is willing to tolerate for the sake of innovation.

- Spend the Budget: As long as the service operates within its SLOs, the development team can deploy features freely. If a bad deployment or incident exhausts the error budget, a code freeze on new features is automatically triggered. All engineering effort is redirected to reliability improvements until the service is back within its SLOs.

The SRE model creates a powerful, self-regulating system that algorithmically balances feature velocity with service stability. While highly effective, this devops teams structure requires significant engineering maturity and a culture that prioritizes data-driven decision-making.

The Platform Team Model

As an organization scales to dozens or hundreds of microservices, the embedded model becomes inefficient and inconsistent. You cannot afford to embed a dedicated SRE in every team. This is the inflection point where the Platform Team model becomes necessary.

A Platform Team's mission is to build an Internal Developer Platform (IDP) that provides infrastructure, tooling, and workflows as a self-service product. Their customers are the internal development teams, and their goal is to provide a "paved road"—a standardized, secure, and efficient path to production.

This team builds and maintains shared, multi-tenant services that all developers consume, such as:

- A centralized CI/CD platform offering pre-configured, reusable pipeline templates.

- A standardized Kubernetes platform with built-in security policies, logging, and monitoring.

- A self-service portal (e.g., using Backstage) for provisioning infrastructure like databases or message queues via API calls or a UI.

- A unified observability stack providing metrics (Prometheus), logs (ELK/Loki), and traces (Jaeger/Tempo) as a service (Grafana).

By productizing the platform, this model dramatically reduces the cognitive load on development teams. They are abstracted away from the underlying complexity of Kubernetes, cloud networking, and security configurations, allowing them to focus entirely on delivering business value. For most large engineering organizations, this model represents the most scalable and efficient end-state.

If you're looking to dive deeper into how these roles fit together, check out our guide on the optimal software development team structure.

Mapping Critical Roles and Responsibilities

Choosing the right DevOps team structure is the architectural blueprint. Now you need to define the engineering roles that will execute it. A well-designed model fails without clearly defined responsibilities, leading to confusion, duplicated effort, and technical drift. Generic job titles are insufficient; we need to specify the technical competencies, core tasks, and key performance indicators for each role.

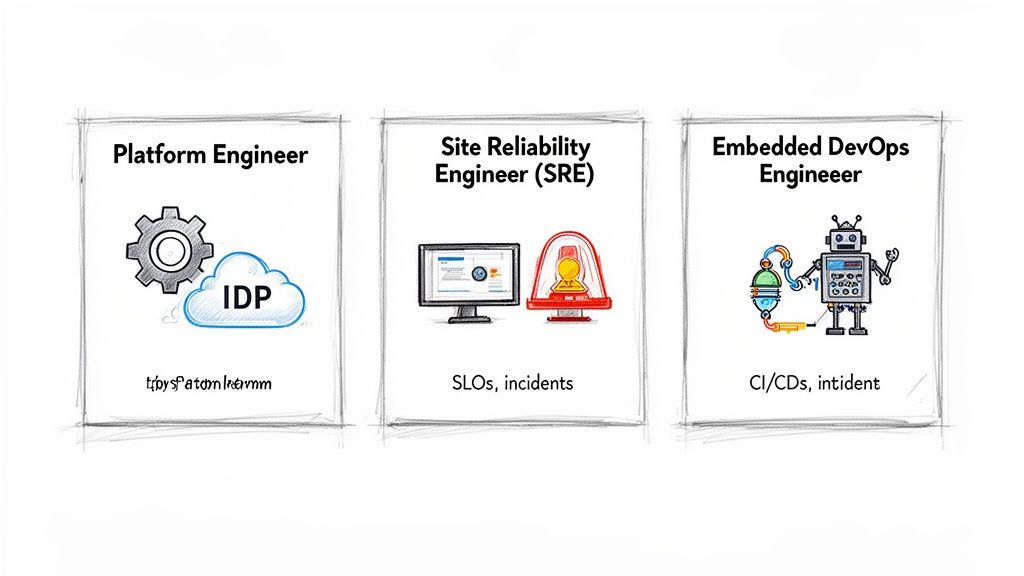

Let's dissect the three primary technical roles that power a modern DevOps ecosystem.

The Platform Engineer: Building the Paved Road

The Platform Engineer is an internal product manager and software architect whose product is the Internal Developer Platform (IDP). Their customers are the organization's developers, and their mission is to build a streamlined, self-service path to production that maximizes developer velocity and minimizes cognitive load.

They achieve this by abstracting away the underlying complexity of cloud infrastructure, Kubernetes, and CI/CD tooling into a cohesive, easy-to-use platform.

Core Technical Responsibilities:

- Building a Self-Service IDP: Using tools like Backstage or custom-built portals, they create a service catalog where developers can provision standardized application environments, databases, or CI/CD pipelines with a single API call or button click.

- Standardizing CI/CD: They engineer reusable CI/CD pipeline templates (e.g., in Jenkins, GitLab CI, or GitHub Actions) that enforce security scanning (SAST/DAST), automated testing, and deployment best practices by default, making the "right way" the "easy way."

- Managing Infrastructure as Code (IaC): They are experts in tools like Terraform or Pulumi, creating a library of version-controlled, reusable, and secure infrastructure modules (e.g., for an RDS database or an S3 bucket with standard policies) that development teams can consume.

A platform engineer's success is measured by platform adoption rates, developer satisfaction scores, and improvements in DORA metrics across the organization.

The Site Reliability Engineer: Balancing Speed and Stability

A Site Reliability Engineer (SRE) operates at the intersection of software development and operations, applying software engineering principles to solve reliability challenges. Their work is data-driven, revolving around metrics like Service Level Objectives (SLOs), Service Level Indicators (SLIs), and error budgets.

An SRE's primary objective is to ensure that services meet their defined reliability targets while enabling sustainable development velocity.

An SRE's mandate is simple but powerful: protect the user experience by enforcing reliability standards. They have the authority to halt new feature releases if a service's error budget is depleted, forcing the team to focus exclusively on stability improvements.

This role requires a constant balance between proactive engineering to prevent failures and rapid, effective incident response.

A Day in the Life of an SRE:

- Morning (Proactive Engineering): The day begins by reviewing Prometheus and Grafana dashboards to check SLO compliance. The rest of the morning might be spent writing a Python script to automate a manual failover process or using Terraform to add a new caching layer to improve service latency.

- Afternoon (Incident Response): An alert fires: P99 latency for a critical API has breached its threshold. The SRE assumes the Incident Commander role, coordinating the response in a dedicated Slack channel. Using distributed tracing tools, they isolate the issue to a memory leak in a recent canary deployment. After a controlled rollback stabilizes the service, they initiate a blameless postmortem, documenting the root cause and creating actionable follow-up tasks to prevent recurrence.

This dual focus ensures the team is not just firefighting but systematically engineering a more resilient system.

The Embedded DevOps Engineer: The Force Multiplier

The Embedded DevOps Engineer is a tactical specialist deployed directly within a single product or feature team. Unlike a platform engineer building for the entire organization, this engineer is deeply focused on the specific technical stack and delivery challenges of their assigned team.

Their goal is not to "do DevOps" for the team, but to enable and upskill them. They sit with developers, pair-programming on CI/CD pipeline configurations, writing IaC scripts for their specific microservices, and teaching them how to build observable, resilient applications from the ground up.

When defining these roles, it is critical to map out the specific technical skills required. Resources like these DevOps Engineer resume templates can provide concrete examples of the real-world competencies that define a high-impact candidate. The embedded model is particularly effective for startups or companies initiating their DevOps journey, as it fosters a culture of shared ownership and delivers immediate value.

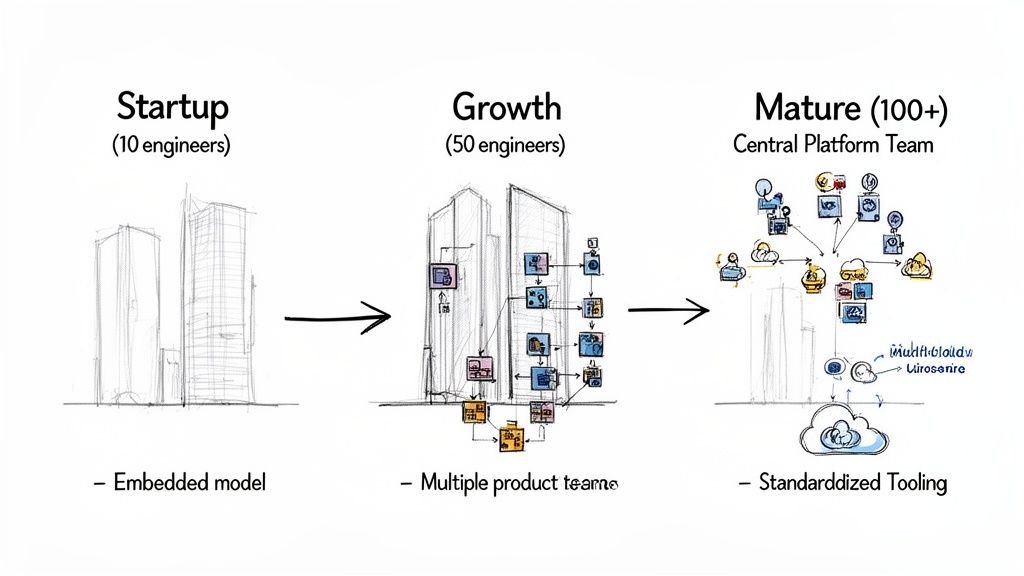

Strategies for Scaling Your Team Structure

A DevOps team structure is not a static artifact. The Embedded model that provides agility for a 10-person startup will create chaos and inconsistency for a 100-person engineering department. As your organization and technical complexity grow, your team structure must evolve with it. Failure to adapt turns your organizational design into your primary bottleneck.

Scaling is about strategically evolving how teams interact and leverage each other's work, not just adding headcount. A key part of this is recognizing the technical triggers that signal your current model is reaching its limits.

Recognizing Key Growth Triggers

Certain technical and organizational shifts are clear indicators that it's time to re-evaluate your DevOps structure. Ignoring these signals leads to duplicated work, tooling fragmentation, and overwhelming cognitive load on developers.

Be vigilant for these scaling inflection points:

- Microservices Proliferation: The jump from a monolith or a few services to dozens of microservices is a primary trigger. At this point, managing bespoke CI/CD pipelines, IaC, and monitoring for each service becomes untenable and creates massive overhead.

- Multi-Cloud or Multi-Region Expansion: Operating across multiple cloud providers (e.g., AWS and GCP) or geographic regions introduces significant complexity in networking, identity and access management (IAM), and data residency. A decentralized approach cannot manage this complexity effectively.

- Repetitive Problem Solving: When you observe multiple teams independently struggling with the same foundational problems—such as setting up Kubernetes ingress, configuring service mesh, or building secure container base images—it's a clear sign of inefficiency. This duplicated effort is a direct tax on productivity.

When these triggers appear, the decentralized, embedded model has served its purpose. It's time to evolve toward a centralized, platform-based model that provides leverage.

The objective of scaling your DevOps structure isn't to reintroduce silos or centralize control. It's to build a leveraged internal platform that makes the secure, reliable, and compliant path also the easiest path for all development teams.

Transitioning from Embedded to Platform Model

Evolving from an Embedded model to a mature Platform Team is a strategic architectural shift. You are transitioning from providing localized, bespoke support to building a centralized, self-service product for your internal developers.

Here is an actionable playbook for executing this transition:

- Identify "Platform Primitives": Conduct a technical audit across your development teams. Identify the common, recurring problems they are all solving. These "primitives" typically include container orchestration (Kubernetes), CI/CD pipelines, observability stacks, and database provisioning. These become the initial features on your platform's roadmap.

- Form a Prototyping "Platform Squad": Charter a small team, often by pulling one or two of your most experienced embedded engineers. Their initial mission is to build a "paved road" solution for one of the identified primitives. A standardized, reusable GitHub Actions workflow for building and pushing a container image is an excellent starting point.

- Treat the Platform as a Product: This is the most critical step. The platform team must have a product manager who engages with developers (their customers) to understand their pain points and gather requirements. The platform's success should be measured not just by its technical elegance but by its adoption rate and impact on developer satisfaction and DORA metrics.

- Launch and Iterate: Release the first platform service (e.g., a self-service tool to create a Kubernetes namespace with standard network policies) to a single pilot team. Gather their feedback, iterate, and then market it internally with documentation and training. When other teams see the tangible time savings, organic adoption will follow.

- Gradually Scale the Platform Team: As adoption increases, you gain the business case to expand the platform team's scope and headcount to tackle more complex primitives. The original embedded engineers form the nucleus of this new team, ensuring it remains grounded in the real-world needs of developers.

This iterative, product-led approach ensures you build a platform that developers love to use, preventing the platform team from becoming an "ivory tower" that dictates standards without providing real value.

Getting From Theory to Practice with OpsMoon

A DevOps team structure on a whiteboard is theoretical. Making it work in a complex technical environment is a practical engineering challenge. The gap between design and execution is where transformations stall, and it's where we provide the critical expertise to succeed.

OpsMoon acts as a strategic, high-impact extension of your team. We embed elite experts directly into your workflow to turn architectural diagrams into functioning, high-performing reality.

Need a senior SRE to embed with a product team and implement SLOs and error budgets from day one? We provide that. Need a dedicated squad to build the core of your internal developer platform from the ground up? We can staff that. Our model is designed for this kind of surgical, high-impact engagement.

We understand that finding specialized talent is a major blocker. 37% of IT leaders identify a lack of DevOps skills as their primary technical gap, and 31% state their top challenge is simply a lack of skilled personnel. This talent scarcity is why specialized marketplaces are critical for accessing top-tier engineers, as detailed in these DevOps statistics on Spacelift.

The Right Expert for the Right Problem

Our Experts Matcher was built to solve this precise problem, connecting you with the top 0.7% of global talent for your specific technical challenges. This isn't about finding a generic "DevOps engineer"; it's about precision engineering.

We connect you with specialists who solve the granular technical problems that define the success of your new structure:

- Kubernetes Cost Optimization: We can embed an expert who will implement fine-grained resource requests and limits, configure cluster autoscaling with Karpenter or Cluster Autoscaler, and optimize pod scheduling to dramatically reduce your cloud spend.

- Advanced CI/CD Security: We can integrate a DevSecOps specialist who can build security gates directly into your Jenkins or GitLab pipelines, using tools like SonarQube for static code analysis and Trivy for container vulnerability scanning, blocking insecure builds automatically.

OpsMoon acts as a force multiplier for your teams. By providing elite, on-demand expertise, we help you crush critical skill gaps, implement best practices faster, and prove the value of your new DevOps team structure without the long delays of traditional hiring.

This approach allows you to build momentum and achieve key technical milestones quickly. The first step is to establish a baseline; our detailed breakdown of DevOps maturity levels can provide a clear benchmark.

Your free work planning session is the first step. We’ll help you analyze your current state, define your target state, and map the precise technical expertise required to get your teams performing at an elite level.

Got Questions About DevOps Team Structures?

Let's be clear: choosing the right DevOps team structure isn't about finding a single correct answer. It's about understanding the trade-offs and selecting the model that best fits your company's current scale, maturity, and technical goals.

Here are direct, actionable answers to the most common questions from engineering leaders.

What's the Best DevOps Team Structure for a Startup?

For most startups, the Embedded DevOps model is the optimal choice. It provides the best balance of speed, context, and capital efficiency.

By placing an experienced DevOps engineer directly within a product team, you embed operational expertise at the point of code creation. Developers receive immediate, context-aware feedback on reliability and scalability, allowing them to solve problems before they escalate into production incidents. This tight loop is critical when speed-to-market is paramount.

The embedded model is also highly capital-efficient. You get senior-level operational expertise applied directly to your most critical product without the overhead and cost of building a dedicated platform engineering department before you need one.

This model also scales effectively in the early stages. As you grow and launch a second product team, you can simply hire another embedded expert for that team without needing to re-architect your entire organization.

How Do I Know if My DevOps Team Structure Is Working?

You measure its success with quantitative data, primarily the four DORA metrics. These are the industry standard for measuring the performance of software delivery. A successful team structure will create measurable, sustained improvements across these four key indicators.

Here’s what to track:

- Deployment Frequency: How often do you successfully release to production? Elite teams deploy on-demand, often multiple times per day.

- Lead Time for Changes: What is the median time from code commit to production deployment? Elite performance is under one hour.

- Mean Time to Recovery (MTTR): When an incident occurs, how long does it take to restore service? Elite teams recover in less than one hour.

- Change Failure Rate: What percentage of deployments to production result in a degraded service and require remediation? Elite teams maintain a rate below 15%.

Beyond DORA, monitor developer satisfaction via surveys. Are developers happy and productive, or are they fighting friction in the delivery process? Also, track the time-to-first-commit for new engineers. If a new hire can ship production code on their first day, your platform and structure are working effectively.

When Is the Right Time to Build a Dedicated Platform Team?

The right time to build a dedicated Platform Team is the moment you observe multiple development teams solving the same underlying infrastructure problems independently. This pattern is a definitive signal that you have outgrown a decentralized model.

If you have several teams all building their own CI/CD pipelines, managing their own Kubernetes clusters, or configuring their own observability stacks (e.g., Prometheus/Grafana), you are wasting significant engineering effort on undifferentiated, repetitive work. This technical fragmentation increases cognitive load and slows down all teams.

A Platform Team is chartered to solve this problem. Their mission is to build an Internal Developer Platform (IDP) that provides infrastructure, deployment pipelines, and observability as a standardized, self-service product. This abstracts away operational complexity, freeing product teams to focus exclusively on building features that deliver customer value.

Consider the ROI: if three teams are each spending 20 hours a week on Terraform configurations, you are losing 1.5 full-time engineers' worth of productivity. A platform team can build a standardized Terraform module that reduces that collective time to nearly zero, creating massive leverage across the entire engineering organization.

The goal is to create a "paved road" to production that makes the secure, reliable, and efficient path the easiest path for every developer.

Building a high-performing DevOps team structure requires not just the right model but also the right expertise. At OpsMoon, we bridge the gap by connecting you with the top 0.7% of global DevOps talent. Whether you need an embedded SRE or a team to build your platform, we provide the specialized skills to accelerate your journey. Start with a free work planning session to get a clear, actionable roadmap for structuring your team for elite performance.

Leave a Reply