A Service Level Objective (SLO) is a precise, quantifiable target for the reliability of a system, typically from the perspective of the user. It's not an abstract metric but a specific, measurable commitment that defines the expected level of performance.

A technically sound SLO is defined with precision. For example: "Over a rolling 28-day window, 99.5% of HTTP GET requests to the /api/v1/login endpoint will complete with a 2xx or 3xx status code in under 300 milliseconds, as measured at the load balancer."

The Foundation of Reliability Engineering

In modern software development, the velocity of feature deployment often conflicts with the operational stability of the service. SLOs provide a data-driven framework to manage this trade-off, transforming "reliability" from a vague aspiration into a formal engineering discipline. They create a shared understanding between development, operations, and product teams, enabling them to make objective decisions based on an agreed-upon error budget.

Think of it as a contract with your users, backed by internal engineering rigor. A pizza delivery service might promise, "99% of our pizzas will arrive within 30 minutes." This isn't a marketing slogan; it's a measurable standard defining operational success.

Deconstructing the SLO Promise

This promise is built on three core components that work together to create a target that is both unambiguous and quantifiable. Each component addresses a fundamental aspect of service performance.

- Service Level Indicator (SLI): This is the raw metric—what you measure. An SLI must be a direct proxy for user experience, such as the latency of an API request or the success rate of a data processing job. For our pizza service, the SLI is the delivery time in minutes for each order.

- Target: This is the desired performance level—how good the service needs to be, almost always expressed as a percentage like 99.5% or 99.9%. This represents the desired success rate over the total number of valid events. The pizza service's target is 99%.

- Time Window: This is the period over which you measure compliance. A rolling window (e.g., 28 or 30 days) is standard, as it smooths out transient anomalies and provides a more accurate, long-term view of service health compared to a static calendar month.

Let's dissect the login SLO example to see how these components fit together in a technical context.

Anatomy of an SLO

| Component | Description | Example (99.5% of logins < 300ms over 30 days) |

|---|---|---|

| SLI | The specific, quantitative measure of a service aspect. It must be derived from a real user journey. | The request latency for POST /api/v1/login. |

| Target | The performance goal, expressed as a percentage of valid events that must meet the success criteria. | 99.5% of login requests. |

| Threshold | The specific performance boundary that defines success for a single event. | The request must complete in less than 300 milliseconds. |

| Time Window | The duration over which the SLO compliance is measured and evaluated. | A rolling 30-day period. |

With this structure, you transform a vague goal like "fast logins" into an objective, falsifiable engineering target.

A well-defined SLO creates a shared language between product, engineering, and business teams. It lets everyone make objective, data-driven decisions that balance the push for new features with the critical need for system stability.

This data-driven approach eliminates subjective debates about whether a system is "fast enough" or "reliable enough." The conversation is grounded in quantitative analysis of performance against a pre-agreed standard.

This is precisely why SLOs are a cornerstone of modern Site Reliability Engineering (SRE) and DevOps. They provide the technical foundation for building and operating systems that are not just functional, but demonstrably dependable. To dive deeper into this world, check out our guide to Site Reliability Engineering.

Connecting SLIs, SLOs, and SLAs

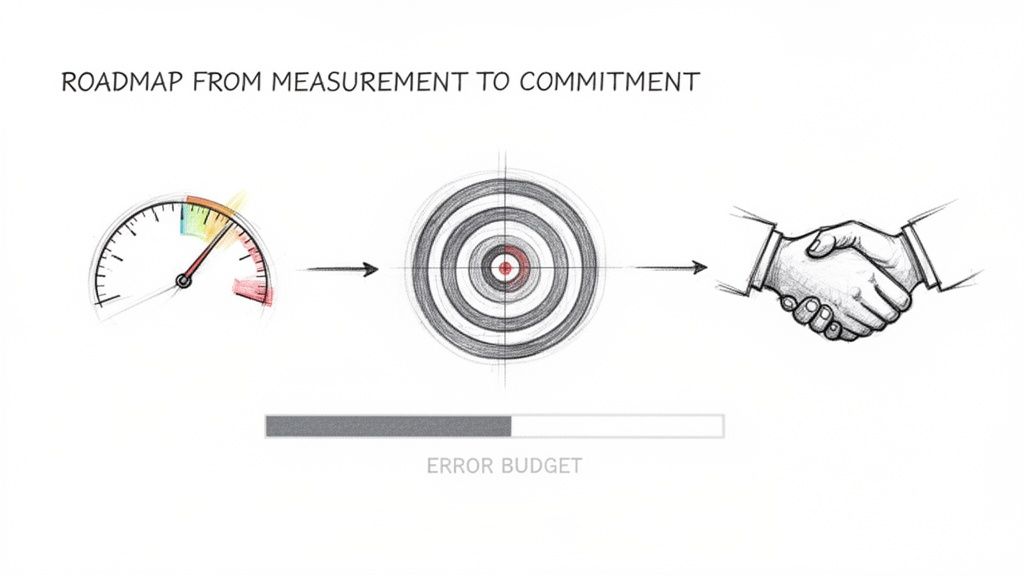

To fully grasp Service Level Objectives, you must understand their position as the critical link in a three-part chain. This hierarchy connects raw system telemetry to binding business contracts. The three components are the Service Level Indicator (SLI), the Service Level Objective (SLO), and the Service Level Agreement (SLA).

This is a logical progression: you first measure performance (SLI), then set an internal goal for that measurement (SLO), and finally, make an external promise based on that goal (SLA).

SLIs: The Foundation of Measurement

A Service Level Indicator (SLI) is a direct, quantitative measure of a service's performance from the user's perspective. It is the raw data—the evidence—collected from your production environment. An SLI itself is not a goal; it is simply a metric that reflects the current state of your system.

Common examples of technical SLIs include:

- Request Latency: The distribution of time elapsed from when a request is received by the load balancer to when the last byte of the response is sent.

- Availability (or Success Rate): The ratio of valid requests that complete successfully (e.g., HTTP

2xx/3xx/4xxstatus codes) to the total number of valid requests (excluding client errors like4xx). - Data Freshness: The time elapsed since the last successful data ingestion or update in a system, crucial for data processing pipelines.

Without well-chosen SLIs, any discussion of reliability is based on conjecture. SLIs provide the objective data needed for engineering analysis.

SLOs: The Internal Performance Target

A Service Level Objective (SLO) codifies an SLI into a specific performance target over a defined period. It is a strictly internal goal that defines what the engineering team considers an acceptable level of service. An SLO is a commitment to yourselves and other internal teams about the performance level you are engineering the system to meet.

An SLO translates a raw SLI into a clear objective. If your SLI measures API latency, a corresponding SLO might be: "99.9% of authenticated API requests to the /users endpoint will be served in under 250ms over a rolling 28-day period."

SLOs provide engineering teams with a clear, unambiguous target that can be continuously measured and validated. The structure—percentage over a timeframe—is powerful because it directly informs the error budget, which is the primary tool for balancing feature development with reliability work. For a deeper dive, you can check out this great analysis of why SLOs matter and how they are structured at statsig.com.

This infographic illustrates the technical hierarchy—SLIs provide the telemetry for SLOs, and consistently meeting those SLOs is what builds user trust and confidence in your service.

This demonstrates that exceptional user experiences are not accidental. They are engineered outcomes built upon a solid foundation of precise measurement (SLIs) and internal commitment (SLOs).

SLAs: The External Business Contract

Finally, the Service Level Agreement (SLA) is a formal, external contract with customers that defines the consequences—typically financial penalties or service credits—for failing to meet specified performance targets. It is the legally binding promise made to users.

The easiest way to tell an SLO from an SLA is to ask: "What happens if we miss the target?" If the answer involves financial penalties, customer rebates, or legal action, it's an SLA. If the consequences are internal—like freezing new feature releases to focus on stability—it's an SLO.

Due to the financial and legal risks involved, SLAs are always set to a more lenient standard than their corresponding internal SLOs. The goal is to under-promise externally (SLA) while over-delivering internally (SLO).

- Internal SLO: We engineer for 99.95% availability.

- External SLA: We contractually promise customers 99.5% availability.

This gap between the SLO and the SLA is your buffer zone. It protects the business. Internal teams are alerted when an SLO is at risk, providing time to remediate the issue long before the customer-facing SLA is ever threatened. By actively managing SLOs, you can confidently meet your SLAs, transforming reliability from a source of stress into a predictable, engineered outcome.

Defining and Calculating Meaningful SLOs

Let's get technical. Translating the abstract concept of "reliability" into a measurable engineering discipline is the core function of an SLO. This process begins with selecting the right Service Level Indicator (SLI).

An SLI is the raw telemetry that proxies your user's experience. A poorly chosen SLI leads to a useless SLO—a phenomenon known as "dashboard green, everything's on fire." You might hit your internal target while users are experiencing significant issues.

The goal is to define SLOs that are ambitious enough to drive engineering improvements but are grounded in historical performance data to be achievable and credible. This is a process of data analysis, not guesswork.

Choosing the Right SLIs for Your SLOs

The most effective SLIs are directly tied to critical user journeys (CUJs). Temporarily ignore system-level metrics like CPU utilization or memory usage. Instead, focus on the user's goals.

User-centric SLIs can typically be classified into four primary categories:

- Availability: Is the service responding to requests? This is the most fundamental measure, usually expressed as the ratio of successful requests to total valid requests. It answers the user's question: "Can I use the service?"

- Latency: How fast is the service? This measures the time to complete an operation, such as an API call or a page load. A latency SLI answers: "Is the service responsive enough for my needs?"

- Quality: Is the service providing a degraded experience? This goes beyond a simple success/failure metric. For a video streaming service, a quality SLI might measure the percentage of streams that play without rebuffering events. It answers: "Is the service performing well, even if it's technically 'available'?"

- Freshness: How up-to-date is the data? This is critical for data processing and content delivery systems. It measures the time delta between when data is created and when it becomes available to the user. It answers: "Is the information I'm seeing current?"

From SLI to SLO: The Core Formulas

Once you have a well-defined SLI, codifying it into an SLO involves defining what constitutes a "good" event and setting a compliance target over a time window.

For an availability SLO, the formula for the SLI is:Availability SLI = (Count of Successful Requests / Count of Total Valid Requests) * 100

A "successful request" is typically an HTTP request returning a status code in the 2xx or 3xx range. "Total valid requests" usually excludes client-side errors (e.g., 4xx codes), as these are not indicative of service failure.

For a latency SLO, you must first define a time threshold. For instance, if "fast" is defined as under 500ms:Latency SLI = (Count of Requests < 500ms / Count of Total Requests) * 100

This approach provides an objective, binary classification for every event.

Why Percentiles Beat Averages

A common technical error is to base latency SLOs on average (mean) response times. Averages are statistically misleading because they are easily skewed by outliers and can hide significant user-facing problems. A single, extremely slow request can be masked by thousands of fast ones, yet that one request represents a moment of acute pain for a user.

Percentile-based SLOs provide a far more accurate representation of the user experience. By targeting a high percentile like the 95th (p95) or 99th (p99), you are making a commitment about the experience of the vast majority of your users, including those in the "long tail" of the latency distribution.

An SLO stating "99% of search queries will complete in under 400ms" is infinitely more robust and user-centric than "the average search query time is 150ms." The percentile-based SLO ensures a consistent experience for nearly all users, not just a good average.

This forces you to engineer for the many, not just the median.

The screenshot below from the Prometheus documentation shows a PromQL expression used to calculate an SLI from raw metrics.

This specific query, rate(http_requests_total{job="api-server",code="200"}[5m]), calculates the per-second rate of HTTP requests that returned a 200 status code over a 5-minute window. This is the type of raw data that feeds into an availability SLI calculation.

Writing and Validating Your SLOs

A robust SLO is unambiguous and leaves no room for interpretation. A good template is:

[SLI] will be [Threshold] for [Target %] of events over a [Time Window].

Here are two technically sound examples:

- Availability:

HTTP GET requests to the /api/v1/users endpoint will return a non-5xx status code for 99.9% of requests over a rolling 28-day window. - Latency:

The p95 latency for image uploads, measured at the ingress controller, will be less than 800ms for 99% of 5-minute windows over a rolling 28-day window.

Before deploying an SLO, validate it with this technical checklist:

- Is it user-centric? Does this SLI directly correlate with user satisfaction?

- Is it measurable? Do you have the necessary instrumentation and telemetry in place to accurately and reliably calculate this SLI?

- Is the target realistic? Is the target percentage based on historical performance data, or is it an aspirational guess? A target should be achievable but challenging.

- Is it controllable? Can your engineering team take direct action (e.g., code changes, infrastructure scaling) to improve this metric?

By applying this rigor, you build a powerful framework for making data-driven decisions that directly enhance user experience.

How to Use Error Budgets for Better Decisions

Defining an SLO is the first step. The real operational value is unlocked by its inverse: the error budget. This simple calculation reframes how engineering teams approach reliability, risk, and innovation.

An error budget is the maximum amount of time your service can be unreliable before breaching its SLO. The formula is simply (100% – SLO Target %). For a service with a 99.9% availability SLO over a 30-day window, your error budget is a slim 0.1%.

This budget is your explicit allowance for imperfection. It empowers teams to stop chasing the myth of 100% uptime and instead use a data-driven framework to balance feature velocity with operational stability.

The Budget as a Risk Management Tool

Treat your error budget as a quantifiable risk portfolio. You can consciously "spend" it on activities that are essential for business growth but may introduce instability. This transforms subjective debates about risk into objective, data-informed engineering decisions.

You can spend your budget on:

- Deploying New Features: Every code change introduces risk. A healthy error budget provides the data-driven justification to proceed with deployments.

- Performing Risky Upgrades: A database migration, a Kubernetes version upgrade, or a core library change are all high-risk operations. The budget quantifies the acceptable risk tolerance.

- Conducting Planned Maintenance: Planned downtime is still downtime. Factoring this into the budget ensures maintenance windows are scheduled and managed without violating reliability targets.

A healthy, unspent budget signals that it's safe to accelerate innovation. Conversely, a rapidly depleting budget is a quantitative alarm. It provides an objective mandate for the team to halt new deployments and focus exclusively on reliability improvements.

Translating Percentages into Practical Units

A percentage like "0.1%" is abstract. To make it actionable for engineers on call, you must translate it into tangible units like minutes of downtime or a raw count of permissible failed requests.

Let's use our 99.9% availability SLO over a 30-day window.

First, calculate the total minutes in the window:30 days * 24 hours/day * 60 minutes/hour = 43,200 minutes

Next, apply your error budget percentage:43,200 minutes * 0.1% = 43.2 minutes

This means your service can be completely unavailable for a total of 43.2 minutes over a 30-day period before breaching its SLO. Suddenly, that 0.1% has concrete operational significance.

This calculation transforms a high-level objective into a clear operational constraint, helping teams understand the impact of every minute of an outage and prioritize incident response accordingly.

Creating an Error Budget Policy

To ensure consistent, predictable decision-making, you need a formal error budget policy. This document should prescribe specific actions based on the remaining budget. This removes emotion and ambiguity from high-stakes situations.

Here is a simple policy template:

| Budget Remaining | Required Action | Example Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| > 50% | Green: Normal operations. Deployments proceed per CI/CD pipeline. | The system is highly stable, allowing for innovation and calculated risk. |

| 25% – 50% | Yellow: Increased scrutiny. All non-critical deployments require peer review and lead approval. Feature flags for new code are mandatory. | The budget burn rate is elevated. Risk must be actively managed to preserve the SLO. |

| < 25% | Red: Deployment freeze on all non-essential changes. Engineering focus shifts to reliability, root cause analysis, and post-mortems. | The SLO is at high risk of being breached. The immediate priority is to stabilize the system and restore the budget. |

This data-driven policy prevents arguments. When the budget is low, the policy dictates the next steps, not a manager's subjective opinion. It aligns the entire team and empowers engineers to protect the user experience. By focusing on reliability, you also improve metrics that speed up incident resolution. To learn more about that, check out our article on improving your team's Mean Time To Recovery.

Implementing and Monitoring SLOs in Your Stack

Defining an SLO is a planning exercise. Implementing it requires building an automated feedback loop into your team's operational workflow. This involves instrumenting your services, collecting metrics, visualizing SLO compliance, and generating alerts when your error budget is threatened.

A properly implemented SLO monitoring stack transforms a static target into a dynamic, real-time compass for your engineering team. Dashboards and alerts become the single source of truth for reliability, guiding everything from daily stand-ups to long-term architectural planning.

Building Your SLO Monitoring Stack

At the heart of any modern SLO implementation is an observability stack. A powerful and widely-adopted open-source combination is Prometheus for metrics collection and time-series storage, and Grafana for visualization and dashboarding.

Here is a breakdown of the technical workflow:

- Instrumentation: Your application code must be instrumented to expose the necessary SLI metrics. This is typically achieved by integrating a client library (e.g., Prometheus clients for Go, Python, Java) that exposes an HTTP endpoint (e.g.,

/metrics) with counters, gauges, and histograms for request counts, latencies, and error rates. - Data Collection: A Prometheus server is configured to "scrape" this

/metricsendpoint at regular intervals (e.g., every 15-30 seconds). It stores this data in a highly efficient time-series database. - Visualization: Grafana is configured with Prometheus as a data source. You then build dashboards with panels that execute PromQL queries to visualize your SLIs, SLO compliance over the time window, and the real-time error budget burndown.

This stack provides a flexible, scalable, and cost-effective foundation for SLO monitoring. For a deeper dive, check out our guide on leveraging Prometheus for service monitoring.

From PromQL to Actionable Alerts

The engine of this system is the Prometheus Query Language (PromQL). These powerful expressions are used to transform raw, high-cardinality metrics into meaningful SLIs.

For example, to calculate a real-time availability SLI for a specific API service, a PromQL query might look like this:sum(rate(http_requests_total{status_code!~"5..", job="my-api"}[5m])) / sum(rate(http_requests_total{job="my-api"}[5m]))

This calculates the ratio of non-5xx requests to total requests over a 5-minute rolling window, providing a live availability percentage. This query is then used to power a Grafana dashboard panel.

Visualization is insufficient; you need automated action. The best practice is to alert on the error budget burn rate, not on the SLO breach itself. An SLO breach is a lagging indicator; the burn rate is a leading indicator of a future breach.

A high burn rate means you are consuming your error budget at an unsustainable pace. You can configure Prometheus Alertmanager to fire an alert when the burn rate exceeds a certain threshold (e.g., "Alert if we are on track to exhaust the monthly budget in the next 72 hours"). This proactive alerting gives the on-call team time to investigate and mitigate before the SLO is violated.

Essential SLO Tooling Categories

A complete SLO implementation requires a toolchain where each component serves a distinct purpose. From data ingestion to incident response, different tools are specialized for different parts of the workflow.

The table below outlines the essential categories for an SLO monitoring framework.

| Tool Category | Primary Function | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Data Collection & Storage | Scrapes, ingests, and stores time-series metrics. | Prometheus, VictoriaMetrics, M3DB |

| Visualization & Dashboarding | Queries and displays time-series data on graphs and dashboards. | Grafana, Kibana |

| Log Aggregation | Collects, indexes, and analyzes structured and unstructured logs for debugging. | Elasticsearch, Loki, Fluentd |

| Alerting & Incident Mgmt. | Routes alerts based on rules (e.g., burn rate) to on-call engineers. | Prometheus Alertmanager, PagerDuty, Opsgenie |

| SLO Management Platforms | Provides a dedicated, often UI-driven, workflow for defining, tracking, and reporting on SLOs. | Nobl9, Squadcast, Datadog |

These categories are not mutually exclusive; many commercial platforms bundle several of these functions. However, understanding their distinct roles helps in architecting a robust solution, whether open-source or commercial.

The Role of Commercial and Integrated Platforms

The widespread adoption of SRE has created a significant market for specialized SLO management tools. The global Service Level Objective Management market was valued at USD 1.43 billion in 2024, indicating serious enterprise investment in reliability. You can see more on this trend over at dataintelo.com.

This has driven observability platforms like Prometheus to develop deep integrations with tools like Grafana, creating a powerful, unified workflow. These integrations are crucial for translating high-level business objectives into the concrete technical metrics that engineers can measure and act upon.

Many commercial observability platforms now offer integrated SLO management features. These tools often abstract away the complexity of PromQL and alerting configuration, providing features like SLO creation wizards, automated error budget tracking, and pre-built reporting dashboards, which can accelerate adoption for teams.

Common SLO Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Defining your first SLO is a significant step, but the path to a mature, data-driven reliability culture is fraught with common technical and organizational pitfalls. Identifying these traps early can prevent your SLO initiative from failing to deliver value.

A common failure mode is for a team to enthusiastically define a set of SLOs, only to find months later that they are ignored and have had no impact on engineering practices or product stability. Let's analyze the most frequent missteps and their technical solutions.

One of the most critical errors is defining SLOs in an engineering silo. When reliability targets are set without input from product and business stakeholders, they are at best a guess. This can lead to over-engineering a trivial service or, more dangerously, under-engineering a critical one.

Another classic mistake is measuring what is easy, not what is important. System-level metrics like CPU utilization or memory are readily available but are poor proxies for user experience. This leads to the "green dashboard" problem, where all internal monitors show healthy, yet customer support tickets are flooding in.

Setting SLOs in an Engineering Silo

This is the most common organizational trap. Left to their own devices, engineers may set a 99.999% availability target for a non-critical internal batch job, wasting significant resources. Conversely, they might set a latency target based on what the system currently does, rather than what users need it to do, thereby codifying a poor user experience.

The Fix: Mandate a cross-functional SLO definition process. Host a workshop with product managers, lead engineers, and business stakeholders. The objective is to identify the 3-5 most critical user journeys (CUJs) and collaboratively define SLOs that protect the performance of these specific workflows. This ensures technical targets are directly aligned with business value.

Choosing Vanity Metrics Over User-Centric SLIs

It's tempting to instrument and track dozens of metrics, creating a false sense of observability. This "death by a thousand metrics" approach results in dashboards filled with noise, not actionable signals. An SLO should be a high-signal indicator of user-facing health.

The Fix: Start with a minimal set of high-impact SLIs. Focus on the availability and latency of the most critical user interactions: login, search, checkout, etc. Nail these first. You can expand your SLO coverage over time, but starting with a few that truly matter demonstrates value quickly and builds momentum for the program.

Failing to Define Consequences for Error Budget Exhaustion

An error budget without a corresponding policy is just a number on a dashboard; it has no teeth. If there are no pre-agreed consequences for exhausting the budget, development teams will continue to ship features, and reliability will inevitably suffer. The budget's power as a decision-making tool is lost.

The real power of an SLO and its error budget is the automatic, data-driven conversation it forces. When the budget is low, the "what should we do?" debate is already settled by a pre-agreed policy.

This disciplined, data-driven approach is why SLO adoption is accelerating. A recent survey found that 82% of organizations plan to increase their use of SLOs, and 95% report that SLOs enable better business decisions. The benefits are tangible: 27% of respondents quantified savings of over $500,000 from their SLO programs. You can dig into more insights on the business impact of SLO adoption on Business Wire.

Got Questions About SLOs?

As teams begin implementing SLOs, many practical and technical questions arise. Here are answers to some of the most common queries from engineering and product leaders.

How Many SLOs Are Too Many?

It's a common anti-pattern to create SLOs for every microservice and endpoint. This leads to alert fatigue and a loss of focus, a state where engineers can no longer distinguish signal from noise.

For most services, a good starting point is three to five SLOs. These should be tied directly to the most critical user journeys (CUJs). For an e-commerce site, this might be: 1) Homepage Availability, 2) Search Latency, and 3) Checkout Success Rate. Prioritizing quality over quantity ensures that your SLOs remain meaningful and actionable.

Aren't SLOs Just Fancy KPIs?

This is a frequent point of confusion. While both are metrics, SLOs and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) serve distinct purposes and are intended for different audiences.

An SLO is an internal engineering target focused on reliability from the user's perspective. A KPI is a business metric that measures overall success.

SLO: An internal-facing engineering objective. It measures user-facing reliability, like "99.9% of API requests must complete in under 250ms." It is owned and acted upon by engineering teams.

KPI: A business-facing metric. It measures business outcomes, like "monthly active users," "customer churn rate," or "conversion rate." It is owned by product and business leadership.

The critical link is correlation. A degrading SLO (e.g., increasing API latency) should be expected to negatively impact a business KPI (e.g., lower conversion rate). This correlation is what makes SLOs a powerful leading indicator of business health.

How Often Should We Revisit Our SLOs?

SLOs are not static artifacts. They must evolve with your product, your architecture, and your users' expectations. A formal review of all SLOs should be conducted on a quarterly basis.

This cadence provides a structured opportunity to analyze historical performance data and ask critical questions: "Does this SLO still represent a critical user journey?", "Is the target too lenient or too strict based on the last 90 days of data?", and "Have user expectations changed?". Major architectural changes or shifts in product usage patterns are also valid triggers for an immediate, out-of-band SLO review.

Ready to build a reliability strategy that actually works? The experts at OpsMoon can help you define, implement, and monitor meaningful SLOs that tie directly to your business goals. Start with a free work planning session today.

Leave a Reply